Introduction

The XB-29 experimental heavy bomber was the result of a series of design developments by Boeing in the late 1930s, culminating in the Model 345. This model was created in response to a January 1940 army requirement for a long-range heavy bomber that could meet the needs of any potential future conflict.

In August 1940, Boeing completed the preliminary design for Model 345, leading the Army Air Corps (AAC) to offer a contract for two flyable prototypes and one static test prototype.

The contract, designated AC-15429, was finalized on September 6, 1940, and stipulated that the first prototype, now referred to as the XB-29, would be delivered in April 1942, with the second following in June. In December of that year, AAC engineers who were inspecting a full-scale mock-up of the aircraft were so impressed that they amended the contract to add a third flyable XB-29.

First Flight

The first XB-29, with serial number 41-002, took its inaugural flight on September 21, 1942 (six months behind schedule), with Chief Test Pilot Edmund T. “Eddy” Allen at the controls and Al Reed serving as the copilot.

The first XB-29 flight crew

Pilot: E. T. Allen

Co-pilot: A. C. Reed

Flight Test Engineer: W. F. Milliken

Asst. Flight Test Engineer: E. I. Wersebe

Flight Engineer: M. Hansen

Radio Operator: A. Peterson

Observer: K. J. Luplow

However, the aircraft experienced numerous issues with its R-3350 engines, which were prone to overheating and catching fire. As a result, by December of that year, the XB-29 had only logged 27 hours in the air from 23 test flights, requiring the replacement of 16 engines, 22 carburetors, and 19 revisions to the exhaust system.

The XB-29 program suffered its first major setback on December 28, 1942, when one of the engines caught fire during a test flight, forcing Allen to return to Boeing Field.

The second XB-29, serial number 41-0003, made its first flight on December 30, 1942, but it also experienced an engine fire, leading to its maiden flight being cut short.

The Allen Accident

Despite being unproven and dangerous, the XB-29 could not be grounded due to the high demand for the aircraft and the pressing need for it in the Pacific theater during World War II. Over 1,600 production B-29s had already been ordered, and testing was far behind schedule. In order to gather the necessary data to make necessary improvements and get the aircraft into production as quickly as possible, it was essential to continue testing and gather as much information as possible.

Tragically, on February 18, 1943, the second XB-29 suffered another engine fire, which burned through the primary wing spar and caused the wing to buckle, resulting in the plane crashing and killing 19 workers at the Frye Meat Packing Plant, as well as the entire XB-29 flight crew.

The crash of the XB-29, which resulted in the death of Eddie Allen, had far-reaching consequences for the B-29 program. It caused concern all the way up the chain of command, including President Franklin Roosevelt, who was already unhappy about the delays in the program.

The USAAF could not afford to allow the program to fail, as the government had invested over $1.5 billion in the project, and the USAAF needed the B-29 not only to help win the war against Japan but also to establish its independence from the Army.

In order to get the program back on track, the USAAF established the “B-29 Special Project” to oversee testing, production, and crew training, with the goal of getting the B-29 into combat by 1944.

The crash was thoroughly investigated from every angle, including questioning witnesses and collecting and examining the remnants of the aircraft both at the crash site and along the flight path. There were 54 major and hundreds of minor changes that were recommended and given priority for evaluation. The major problems centered on the engines, nacelles, and surrounding structures, which needed to be redesigned to isolate and minimize the potential for fire.

The third XB-29, serial 41-18335, made its first flight on May 29, 1943, with Colonel Leonard Jake Harmon at the controls and Lt Colonel Abram Olson serving as the copilot. This prototype incorporated numerous engine revisions based on the experiences with the first two XB-29s.

XB-29 vs B-29

There were several differences between the B-29 prototypes and production B-29s. One of the most notable differences was in the gunners’ sighting blisters. The prototypes featured smaller, teardrop-shaped blisters, as well as an observation dome for the aircraft commander located aft of the canopy. In contrast, production B-29s featured larger, semi-spherical blisters.

However, the third prototype (sn 41-18335) had a unique configuration, featuring both the semi-spherical blisters of production models and the commander blister of the earlier prototypes.

Another significant difference between the prototypes and production models was the engines. The prototypes were equipped with R-3350-12 engines with 17-foot diameter three-bladed propellers. As mentioned early, these early engines were very problematic due to overheating.

Additionally, the prototypes did not have gun turrets.

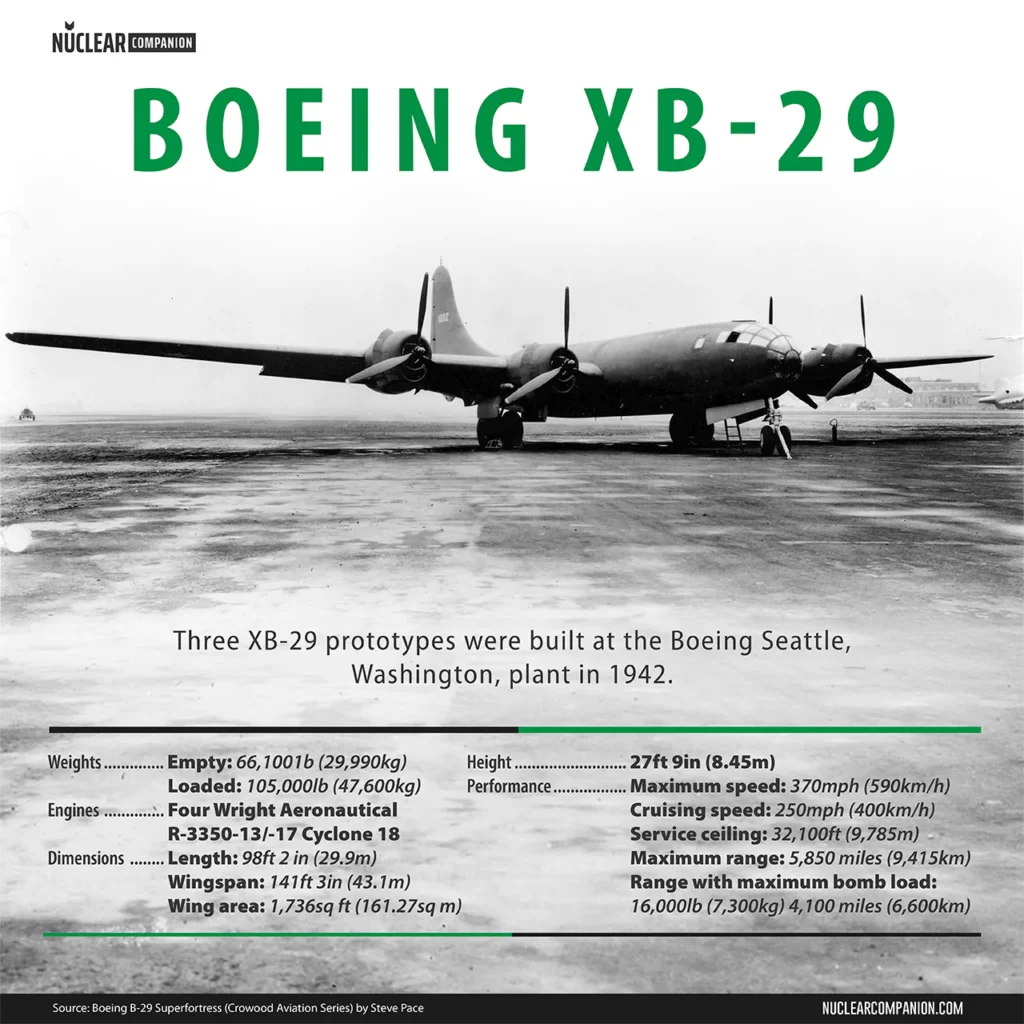

XB-29 Specification

Source: Boeing B-29 Superfortress (Crowood Aviation Series) by Steve Pace

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Weights | |

| Empty: | 66,100lb (29,990kg): |

| Loaded: | 105,000lb (47,600kg) |

| Engines: | Four Wright Aeronautical R-3350-13/-17 Cyclone 18 air-cooled radial |

| Dimensions | |

| Length: | 98ft 2 in (29.9m); |

| Wingspan: | 141ft 3in (43.1m); |

| Wing area: | 1,736sq ft (161.27sq m); |

| Height: | 27ft 9in (8.45m) |

| Performance | |

| Maximum speed: | 370mph (590km/h); |

| Cruising speed: | 250mph (400km/h); |

| Service ceiling: | 32,100ft (9,785m); |

| Maximum range: | 5,850 miles (9,415km); |

| Range with maximum bomb load 16,000lb (7,300kg) | 4,100 miles (6,600km) |

Planes

(S/N 41-0002) “The Flying Guinea Pig”

The first XB-29 had a total of 576 flying hours on it including Eddie Allen’s 27 hours. On 11 May 1948, it was scrapped.

(S/N 41-0003)

(S/N 41-18335) “Gremlin Hotel”

Later, It was sent to Wichita to assist in the establishment of the production line and underwent armament and accelerated flight testing by the USAAF. Unfortunately, it too eventually crashed.

Further reading

Bibliography

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress (Crowood Aviation Series) by Steve Pace

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress: The Ultimate Look: From Drawing Board to VJ-Day by William Wolf

- B-29 Superfortress In Action by David Doyle