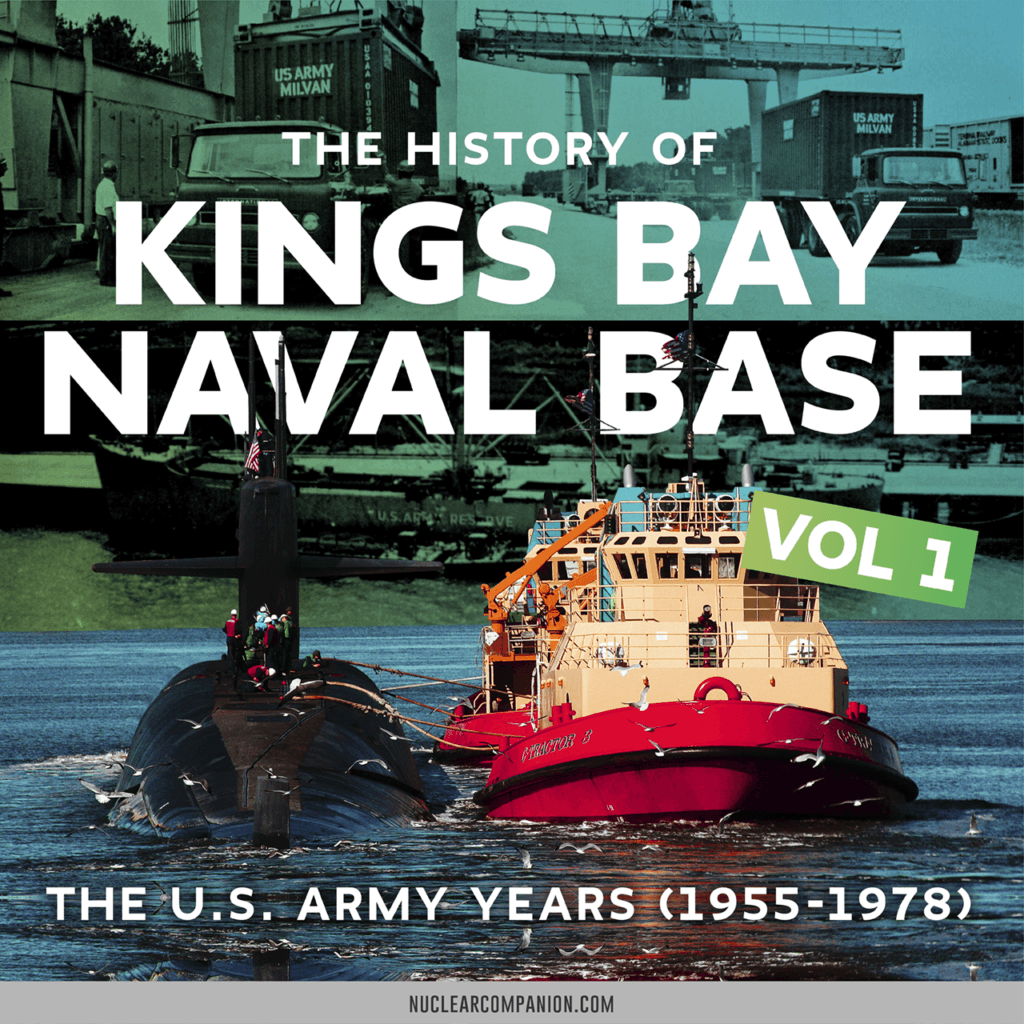

Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay is the East Coast homeport for U.S. Trident nuclear submarines. It is an ultramodern naval base that cost $1.6 billion to build — a Navy record cost for a peacetime construction.

This post is the first one in a series of articles related to Kings Bay History.

Today I’m going to guide you through the years prior to the U.S. Navy’s arrival to Kings Bays.

The ammunition terminal years.

Let’s get started.

A new Sub Base

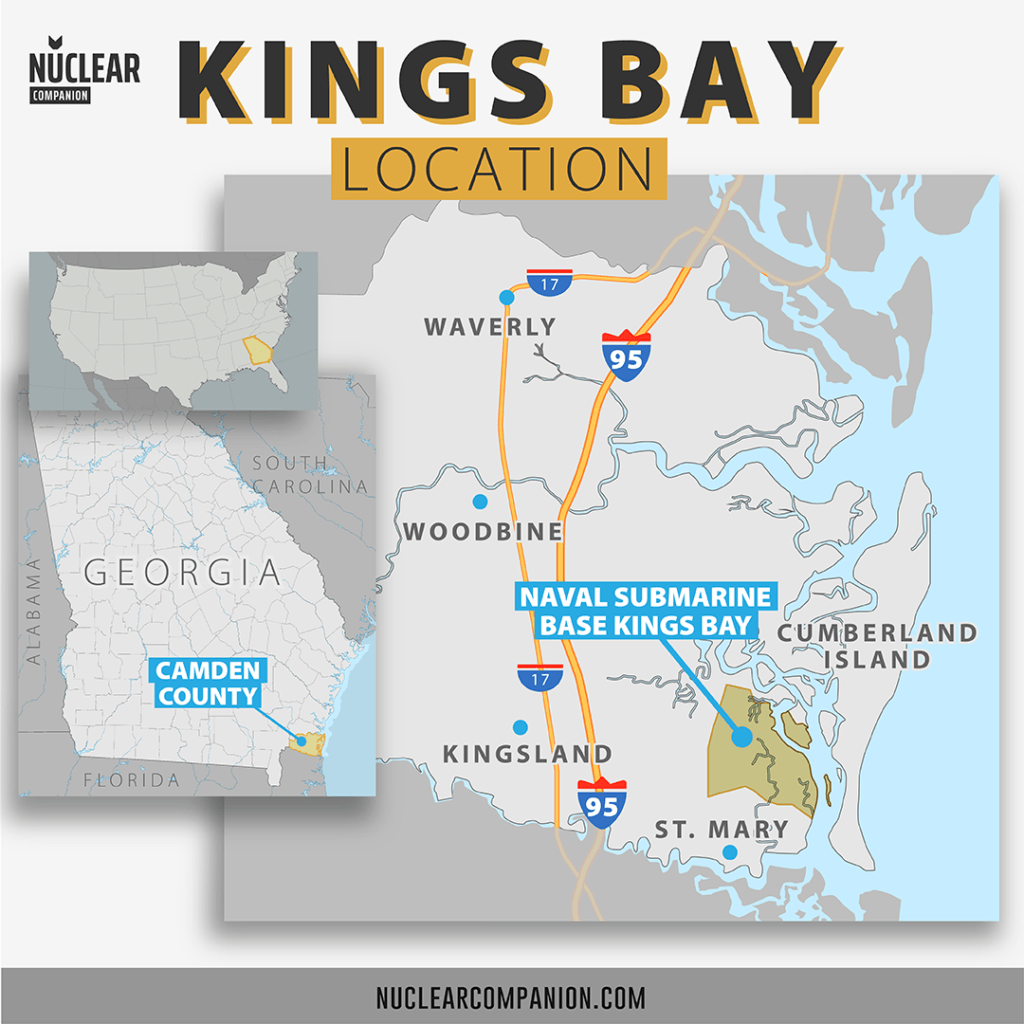

On Oct. 23, 1980, the US Naval Secretary made a major announcement. They had selected the port in the east coast which would house their new Trident submarines. The little county of Camden, Georgia, was the chosen place.

The construction project for the port would be one of the largest ever undertaken by the US Navy. It cost roughly $1.6 billion! In comparison, the Bangor Base (Washington), also housing Trident submarines, cost $700 million.

The Kings Bay Submarine Base would be one of the most impactful constructions of the county’s history. Both socially and economically. Not only brought more people into the county but also created more jobs and opportunities for those already living in the area.

Old Camden County

Such growth is even more stunning considering that thirty years before Camden’s Bay was a zone of wetlands and marshlands. Ruins were scattered throughout the abandoned plantation of landowner Thomas Kings, to whom the bay owes its current name.

Before the base construction, the area had been sitting stagnant for over 100 years. When the Navy began construction, there were only a few buildings on the Kings Bay land. Potentially built in the 1940s, there were two brick houses, a garage, and a storage shed.

Camden County neither was very populated at the time, with only 7,322 inhabitants. Before the submarine base was completed, the largest employer in the area was the 250-acre Kraft Corporation wood pulp mill. This subsidiary of the Gillman Paper Company had been operating out of the city of St. Mary since 1941.

But all this changed with the development of the Kings Bay Submarine Base. The workforce required would attract residents to the area. Through the years, the base would provide a stable source of income for its employees.

But, before the Navy, it was the U.S. Army that saw an opportunity in Kings Bay…

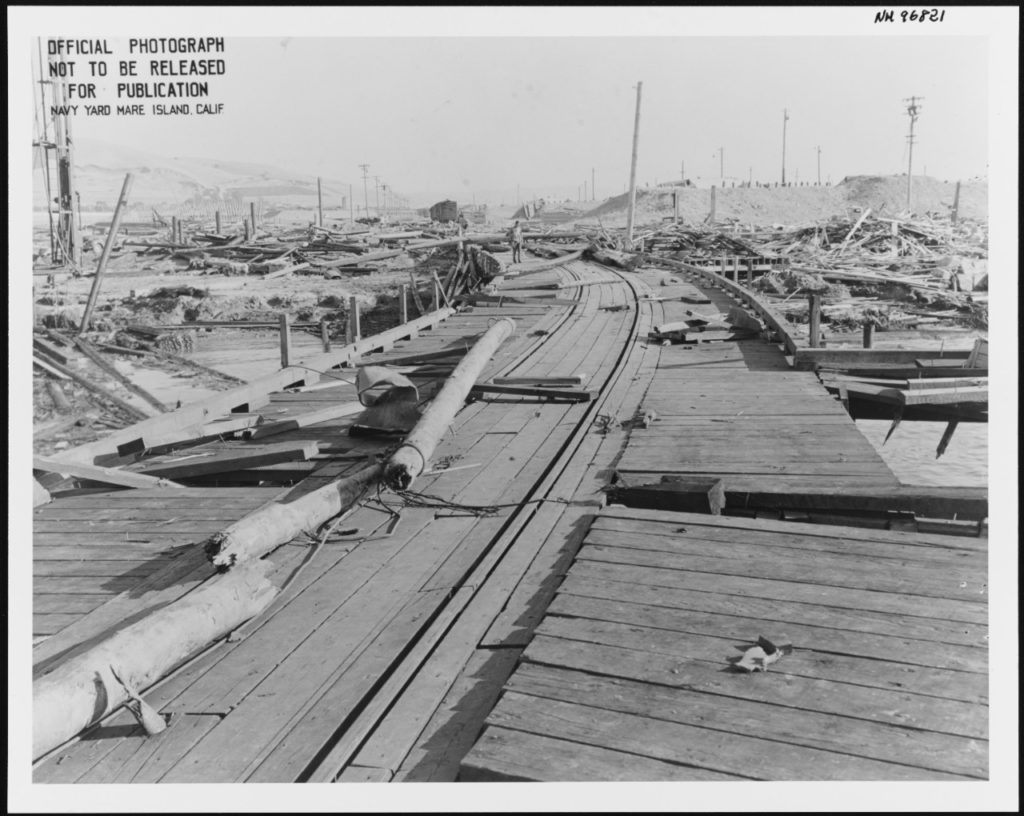

Military ports and a history of tragical accidents

To begin with, the U.S. Army interest in Kings Bay was due to two ammunition accidents. Both of them occurred at different marine bases.

The Chicago Port Disaster

The first one took place on Jul. 17, 1944, at the Chicago Harbor Naval Magazine located in Chicago Port, California. It was the worst disaster to occur on the home front during World War II.

The ammunition for the Pacific theater, loaded onto the SS EA Bryan, exploded. As a result, 320 sailors lost their lives, and at least 390 were injured.

Even the town, next to the terminal, took heavy damage. Most houses and almost every business located in Chicago Port suffer damages.

At least 100 injuries were recorded. The flying elements of debris, metal, and glass were responsible for the destruction.

The Port of Texas City Disaster

Only three years later, on April 17, 1947, the worst industrial disaster in the US took place. Again, in the middle of a shipping operation. The place, the industrial zone of the port of Texas City, located on Galveston Bay in Texas.

Ammonium nitrate destined to aid Europeans devastated by World War II caught on fire. The freighter Grandcamp explosion led others throughout the industrial zone.

The chain reached other ships as well as the chemical plants of Union Carbide and Monsanto. There were hundreds of casualties, from employees to passersby, and thousands of wounded.

These two incidents forced the military to take measures. It began an extensive research into the construction and planning of ammunition loading terminals.

Building the Military Ocean Terminal Kings Bay (MOTKI)

The need for new terminals

Tensions increased due to the Berlin blockade and the Korean War. The United States realized that the risk of a war in Europe was not unlikely.

They needed to prepare in case of its NATO allies required its help. The threats were no other than the Soviet Union and its satellite states.

The thing is that if a war did occur within Europe, it would be necessary for the US to transfer ammunition to their allies through the east coast. With that in mind, the military had to address its lack of port terminals. Not without acknowledging how to prevent any future disasters.

Choosing the right place

Hence began in 1950 a coastal zone survey throughout the east. During this process, the military identified several criteria to assess the value of each considered place:

- Adequate and safe access to regular deep-water shipping channels

- Decent proximity to a mainline railroad

- High-standard, all-weather highway access

- A reasonable supply of local labor

- Climatic conditions that favored year-round operational availability Minimum hazards by adverse weather conditions

- A sufficient amount of open land. This was crucial for the acquisition and construction of transportation and storage facilities

- A low population density in the general region

Kings Bay met these criteria. It wasn’t the only one, though. There were two other sites also selected:

Sunny Point, located 15 minutes south of Wilmington, North Carolina on the Cape Fear River, and Point-aux-Pins, located in Alabama.

The final decision of choosing Kings Bay, nonetheless, was primarily based on its proximity to two major railways.

The Sunny Ocean Military Terminal (MOTSU) would cost $23 million. It would be the Army’s main ammunition loading facility. For its part, the Kings Bay Military Ocean Terminal (MOTKI) would cost roughly $14 million and would serve as a backup facility.

In the event of MOTSU becoming inoperable, Kings Bay would send ammunition from Redstone Arsenal. It would even send from as far west as Red River.

Lessons learn from previous accidents

After the aforementioned disasters, the military learned to proceed with caution. Building a terminal to transport ammunition required taking special precautions.

The military realized that space was a critical factor. They created a “quantity safety distances” protocol.

This protocol specified that the area for construction should have at least 20,000 acres. This kept civilians outside of the reservation, safe from any unforeseen explosion.

For shorter terrains, there was also a protocol for building earthen barricades. In case of emergency, they would help to shelter civilians. It would also create some leeway regarding the area requirement.

At Sunny Point, the constructed barricades were up to 16 feet high and 8 feet wide at the top. It was enough to keep civilians safe, despite the fact that there were less than 20,000 acres of land dedicated to the terminal.

The military also realized that their terminals were neither equipped nor fit to be despots. As such, any cargo brought into the terminal was required to be loaded onto the waiting vessel with as few delays as possible. The capacity for storage in the terminal presented an undue risk.

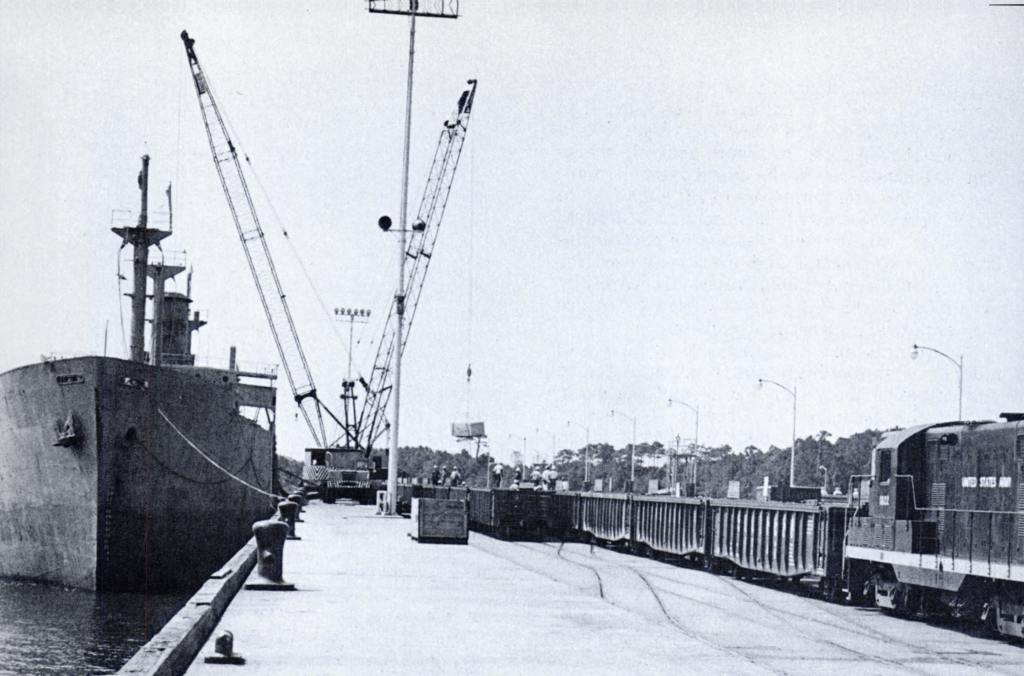

The military also realized that space for trains was vital. In order to continue receiving shipments, the terminal had to be accessible both by road and by rail.

The previously mentioned Sunny Point terminal design had these items in mind:

- Shipments arrived at the terminal, often by train, and were delivered shipside.

- There were three dedicated wharves for receiving these ammunition deliveries. Each of them measuring roughly 2,200 feet long by 87 feet wide, with three sets of tracks on each wharf.

- Additionally, the military designed space for classification and holding yards. They had a 780 and 600-car capacity. The holding yard holds cars whose contents need to be segregated, often by type of ammunition, before they can arrive at individual ships.

In addition to the railroad infrastructure, trucks could also make deliveries in a very similar process.

Construction of Kings Bay terminal

In 1952, the Army authorized the construction of the Sunny Point terminal in Wilmington, North Carolina. It took its Corps of Engineers until Nov. 1, 1955, to make it fully operational, with a total initial cost of $23 million.

Additionally, in 1954, funds aided land acquisition and dredging in Alabama. Later in there the construction of the Point Aux Pins terminal began.

But despite the fact that Sunny Point was fully operational, the military made the construction of a second terminal a priority. As such, they selected the site that would later become the Kings Bay terminal.

The military base at Kings Bay was to serve as a backup, in case Sunny Point became inoperable for any reason.

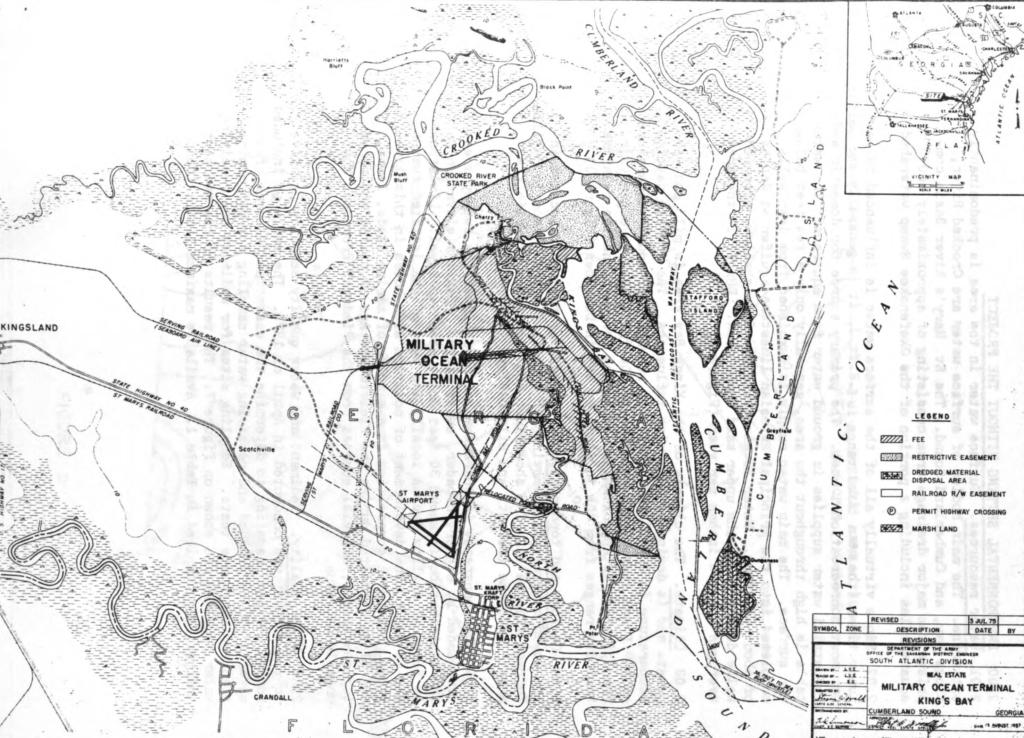

In 1954, the US Army announced the building of a second terminal in Georgia, with a total cost of $21,657,000. The project received authorization in 1953.

The money was for land acquisition, dredging, and the construction of one wharf on the site. Construction began in 1955, and both the wharf and its supporting facilities were completed around Oct. of 1956.

The Army Transportation Corps constructed the approach channel for Kings Bay in 1957. The Army chose its location due to the specific properties of the area. Dredging of the approach channel, turning basin, and wharf zones could be done less frequently, saving the Army both time and resources.

Nevertheless, if the dredging was not accomplished in a specific amount of time, the cost of shipping would actually increase. It would do so until oceangoing vessels would no longer be able to use the Kings Bay terminals at all.

Dredging was also required at Sunny Point since it served as the East Coast’s primary port. The dredging took place every 18 to 24 months, on a cyclical basis, beginning alongside the base construction. Also, the operation of Sunny Point’s terminals would need maintenance of the main navigational channel of the Cape Fear River.

The project required a specific design of the approach channel, turning basin, and wharf areas.

The most prominent feature of the terminal was its 2,000-foot long by 87-foot wide concrete and steel wharf. No less great, there were also three parallel railroad tracks. They allowed several ammunition ships to load simultaneously from both railcars and trucks.

Around the base, the Army built 47 miles of railroad tracks for easy access by railcar, along with a system of roads for ammunition delivery by truck. Also, spurs off of the main rail line led to temporary storage areas.

On the other hand, earthen barricades protected these areas against shrapnel in the case of explosions. These walls were also designed to localize the damage if an accident occurred. To this day, they are still prominent features throughout many areas of the base.

Profiting with an idle base

Blue Star Shipping Corporation

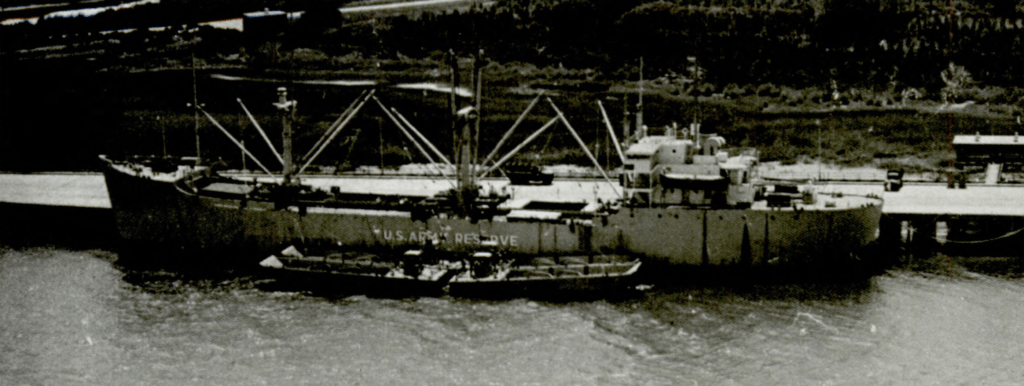

Strangely enough, since there was no immediate need for Kings Bay Port, it held an inactive status. However, a civilian workforce of 18 personnel worked on a full-time basis to operate the base. Also, it was still used by the Army for other missions apart from its primary, intended purpose.

By 1958, the government realized that the terminal was simply sitting empty. They looked, then, for a way to generate income with it while maintaining the integrity of its mission.

The government called on interested parties to lease the terminal, along with the adjacent space. On Sep. 22, 1958, the Army signed with the Blue Star Shipping Corporation, a company run by Raymond A. Forker and based in Savannah. The offer consisted of $10,000 per year for use of the facility valued at $12 million.

Forker was a Navy veteran who served during World War II, and after the war was over became an entrepreneur. The government drafted a contract: DA (s) -09-133-ENG-1076.

Also, he was allowed to use 151 acres of land as a marine terminal, a facility for storage, and another one for the repair and maintenance of their ships. The contract gave them the right to do so over a term of 30 years. The lease began on Oct. 1, 1958, and had a drafted end date of Sep. 30, 1988.

The payments were also stated within the contract. The first year’s minimum was set at $6,000, the second year’s $12,000; the remaining 27 years’ at $18,000.

The Army was due to receive one-twelfth of the yearly rent each month. In order to account for inflation, Blue Star would also pay for the year after the first 90 days based on a government-derived formula.

In exchange for their payments, the Army, in turn, guaranteed that there would be a minimum water depth of 26 feet at Kings Bay. This forced them to conduct dredging operations roughly every five years. If this water depth was not maintained, Blue Star could cancel the agreement at any time.

It is also worthy of mention that, should the Army need to mobilize from the terminal at any time, Blue Star’s personnel would have to leave after 30 days. Plus, their capital improvements would need to be removed 90 days after the Army’s notice.

The Blue Star Shipping Corporation initially occupied the terminal on Oct. 1, 1958. Yet, their operations would take between 60 and 90 days to be fully underway.

Return to military activity and emergency shelter

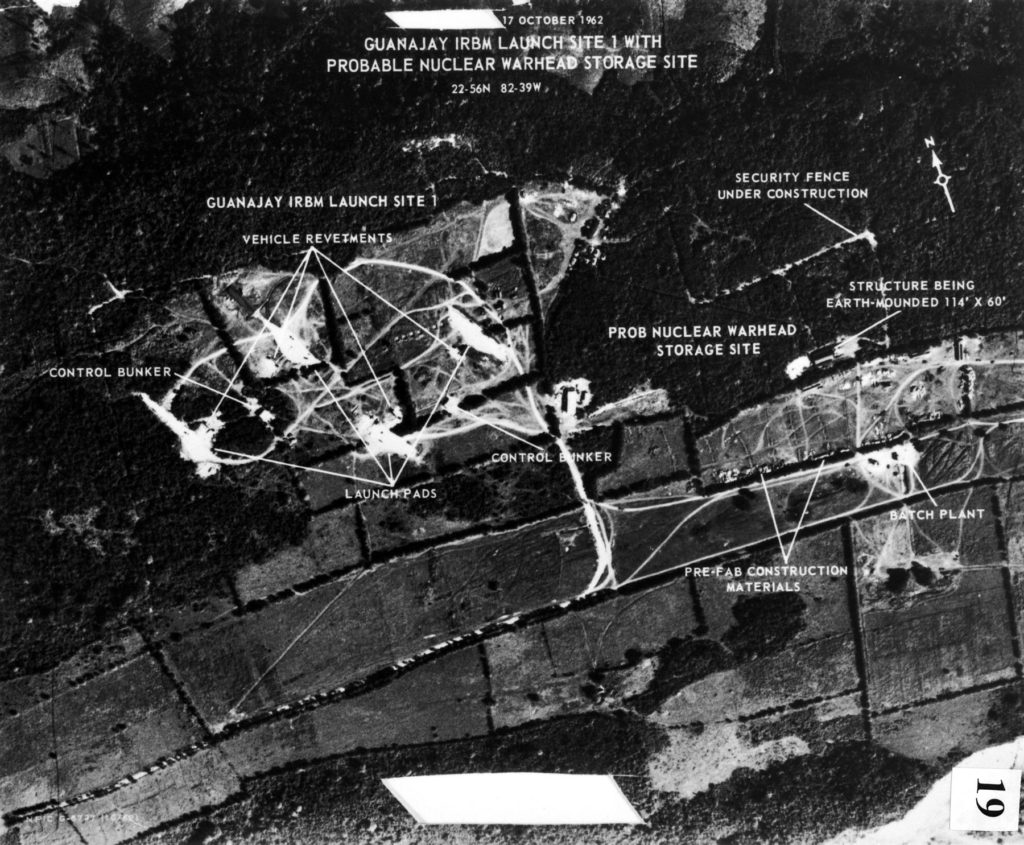

The Cuban Missile Crisis

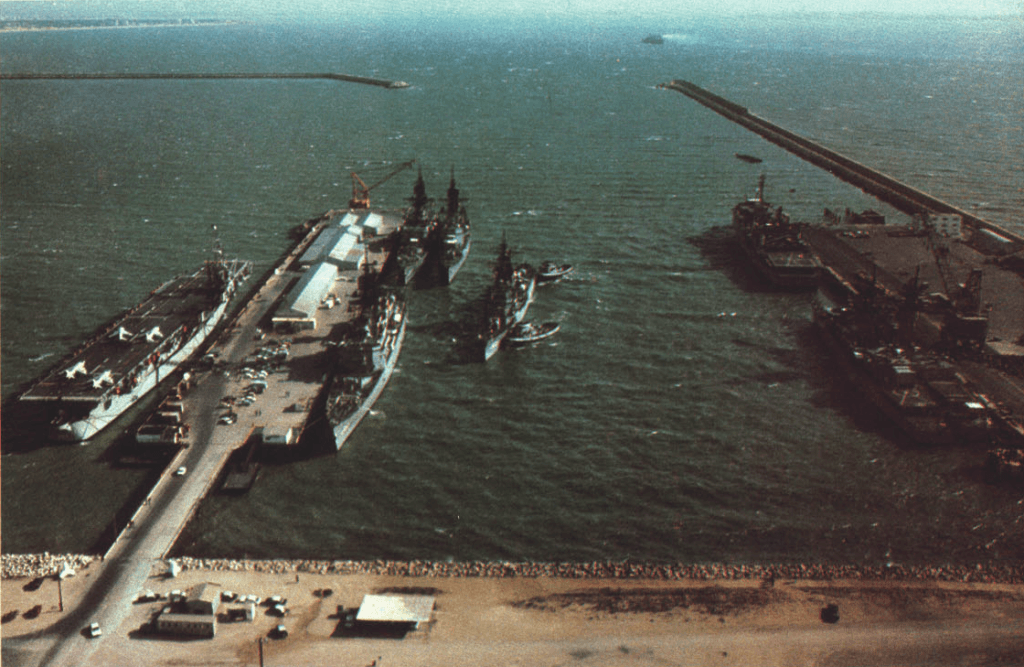

When the Cuban Missile Crisis began in 1962, the military found a new use for Kings Bay. Given its location, it became a meeting point for several units traveling to Florida, from where they could travel to Cuba.

On Oct. 20, 1962, the 159th Transport Battalion of Fort Eustis, Virginia, attended to an Army Annual Training Test. It took place in Smith Island, North Carolina.

While there, the battalion received orders to mobilize toward Kings Bay. They would continue to Ft. Lauderdale in case they were needed for the invasion of Cuba.

There were 1,100 men and 70 boats in the 159th Transport Battalion comprised of:

- The 329th Transportation (heavy boat) Company

- The 1097th Transportation (medium boat) Company

- The 1099th Transportation (medium boat) Company and

- The 73rd Floating Craft Maintenance Company.

The 329th had twelve 1466 LCUs (Landing Craft Utility), while the rest of the companies had forty LCM 8s (Landing Craft Mechanized Mark). Each 1466 LCU was 119 feet long and had a displacement of 183 tons. In contrast, each LCM 8 displaced 58.7 tons and measured 73 feet in length.

In addition to these crafts, the battalion had also numerous Boats, J-boats, and Q-Boats. They even had other ships such as the USAV Lt. Col. John U.D. Page (BDL X1, or Beach Discharge Lighter) which measured 338 feet in length.

Throughout the battalion’s time in Kings Bay, various personnel slept in tents. They had to endure bites from several different creatures, including mosquitos and vipers.

They continued their progression to Ft. Lauderdale. Located there, they waited until Dec. 10, 1962, before being redeployed at the end of the crisis.

Hurricane Dora

Not much after that, Kings Bay would serve as a shelter, a purpose that was already foreseen in its design. In Sep. 1964, the terminal housed 73 victims of Hurricane Dora.

The people were primarily from the nearby town of St. Mary. The city saw winds up to 200 kilometers per hour, along with heavy rains and flooding.

This hurricane, which made landfall south of Jacksonville the night of September 9, caused a significant amount of damage. In both Glynn and Camden counties left three people dead and many more unable to return to their homes. The estimated damages were around $220 million, almost $2 billion in our current days.

New management: Kings Bay becomes (partially) a training facility

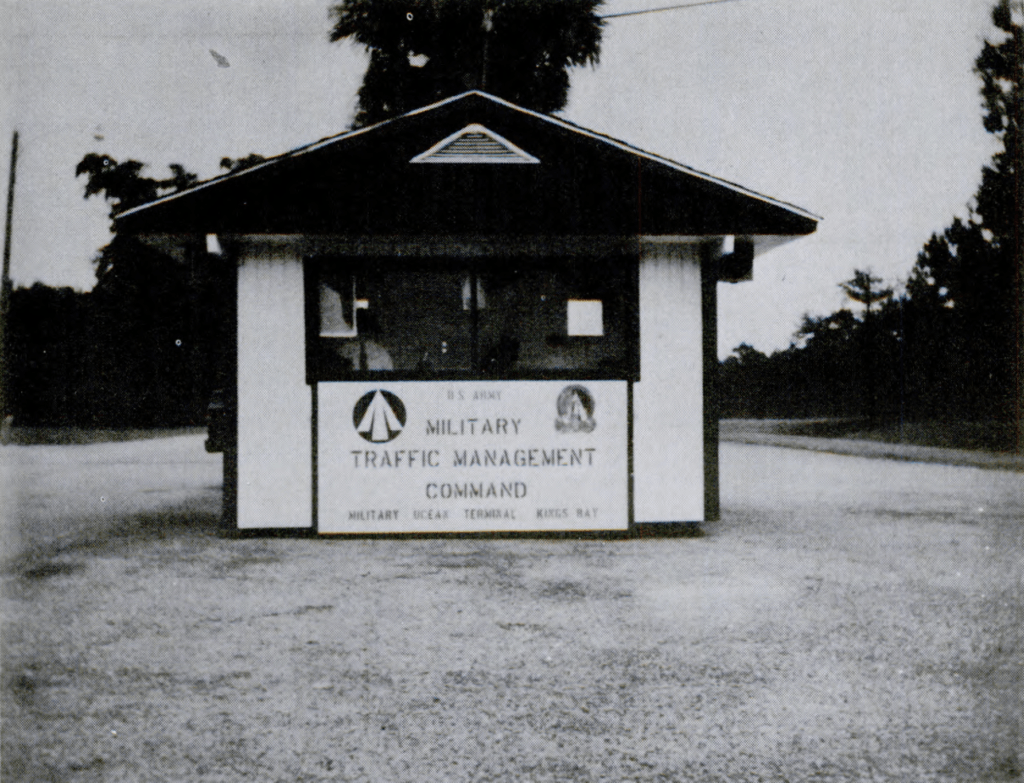

On Feb. 15, 1965, the Military Traffic Management and Terminal Service was created. Its duty was to coordinate the military traffic and to assume responsibility for terminals operation.

This included Kings Bay, which until then depended on the U.S. Army Supply and Maintenance Command.

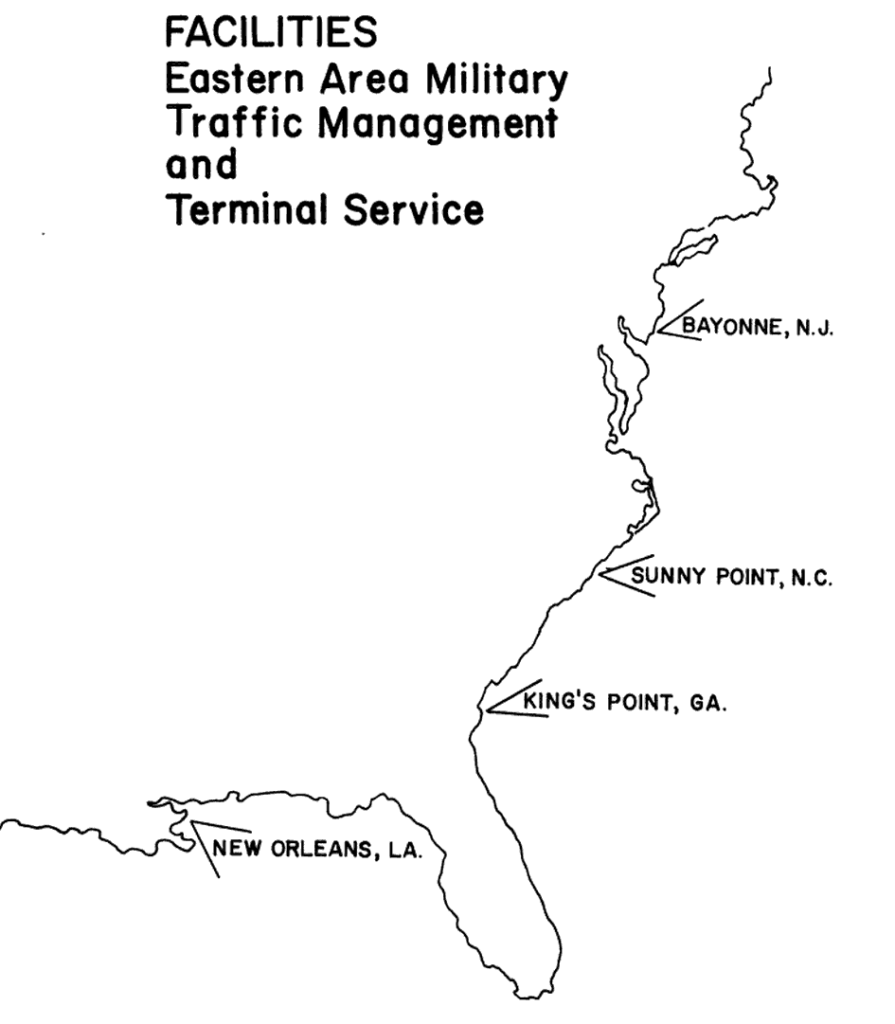

On April 1, 1965, appeared the eastern division of the Military Traffic Management and Terminal Service, based in Brooklyn, New York. This division took hold of several military sites: the Bayonne, Hampton Roads, Sunny Point, our Kings Bay, and New Orleans terminals. Also, of other facilities located in Baltimore, Boston, and Charleston.

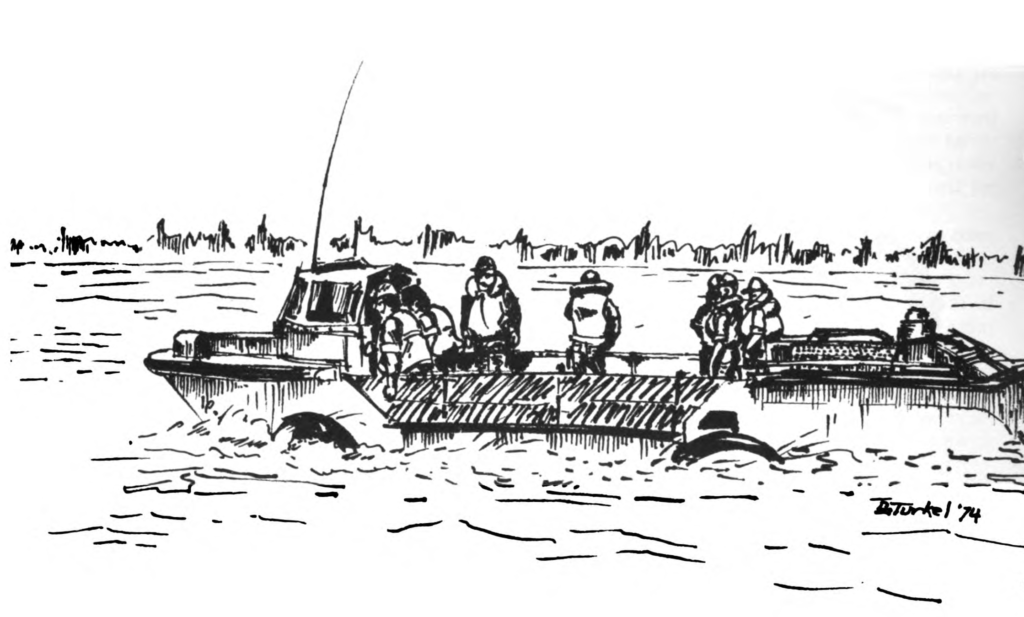

Starting in 1971, this new institution dictated that Kings Bay required to be available one month per year for reservists. The motive was for them to carry out transportation-oriented exercises.

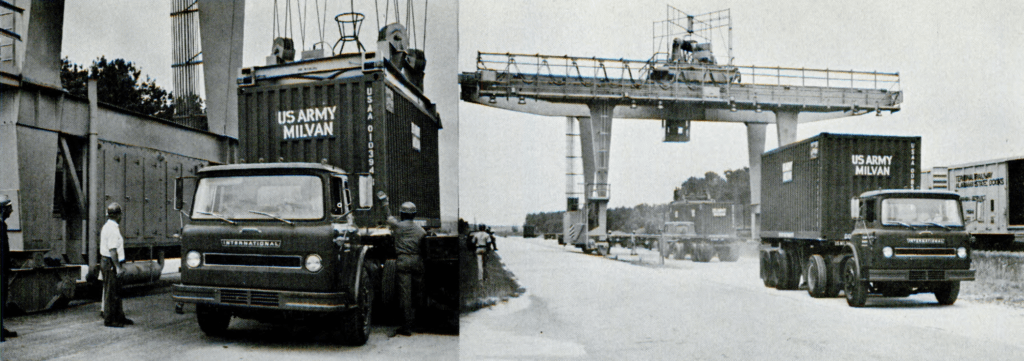

These exercises took place in two rotations of two weeks each. They consisted of 1,500 reservists learning things such as how to prepare and operate a port or to load and unload ammunition. Reservists were also to learn how to purify water and use the railroad system that the Army had constructed nearly two decades earlier.

During the training sessions of 1973, the “MOTKI 73”, several units operated in the terminal:

- The 81st Army Reserve Command of Atlanta

- The 3220th US Army Garrison from West Palm Beach, Florida

- The 143rd Transportation Brigade from Orlando, Florida

- The 32nd Transportation Group from Tampa, Florida

- As well as other units from Washington, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi.

There was also training conducted in Apr. 1974: “MOTKI 74” and Operation Cherokee Rose. Several units participated in them as well:

- The 81st Army Reserve Command of Atlanta

- Army National Guard units from Mississippi and South Carolina

- Logistics units from the 79th, 97th and 1200th US Army Reserve Command

- Ten members of the Women’s Army Corps Reserve

- A maintenance assistance and instruction team from Readiness Group Atlanta

- The 3220th US Army Garrison, which operated a quartermaster sale store

- The 437th Medical Detachment of Fort Lauderdale.

On Jul. 31, 1974, the Military Traffic Management and Terminal Service gained a new name. It became known as the Military Traffic Management Command, under the dictations of the Total Army protocol.

This protocol required the port to hold 21 ready units from the Army Reserve at all times in case of mobilization. In such a case, Kings Bay would be controlled by the 1188th Ocean Terminal Unit based in East Point, Georgia. The base would take care of moving ammunition through the Military Ocean Terminal.

The 1188th Ocean Terminal Unit

1188th Unit’s history began in Mar. 1958 as an Army Terminal Unit. From there on, it worked as a Terminal Unit, then an Outport Unit and finally an Ocean Terminal Unit.

In times of peace, the 1188th was under the command of the US Army Forces Command. If mobilized, the unit would report to the Military Traffic Management Command.

This Command would provide to the unit 30 officers and 31 personnel. Those numbers were for handling the annual capacity of up to 970,000 tons of explosives at Kings Bay.

No other port as Kings Bay

Blue Star’s initial activity and operational volumes were modest. And yet, there were several prospects for growth.

Their main shipments were explosives components for South America. Potential port users and Blue Star clients at the outset were explosive manufacturing companies. Some of them were Southern Nitrogen Co., Stevens Shipping Co. of Savannah, Baker Brothers Fertilizer Co. of New York, Martin Lumber Co. of Brunswick, and St. Mary’s Kraft Corporation.

Additionally, Blue Star built two warehouses. One with a 32,000-square-foot capacity and another with an 11,200-square-foot capacity in the early years of their port occupation.

Kings Bay would soon become the only port on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to handle large commercial shipments of explosives. Between Oct. 1973 and Sep. 1974, 6,000 tons of explosives and 20,000 tons of general goods passed through Kings Bay alone.

By 1975, there were 32,000 tons of goods passing through the terminal annually. Blue Star employed 18 local workers, most of their laborers were from Jacksonville, Florida.

There was no other facility meeting the various federal agency regulations. And no other port with the capability of loading large amounts of explosives into deepwater ships for export. Most of these explosives were destined for commercial mining and construction projects.

Between May of 1975 and June 1977, 52 million worth of explosives and other cargo were shipped through Kings Bay.

Manufacturers of commercial explosives with considerable use of the terminal at the late 70s were:

- Du Pont (based in Wilmington, Del.)

- Atlas Powder Co. (based in Miami)

- Olin Winchester International (based in New Haven, Conn.)

- Hercules Inc. (based in Wilmington, Del.)

But, there was a problem. Army requirements didn’t let the full exploit of the installations.

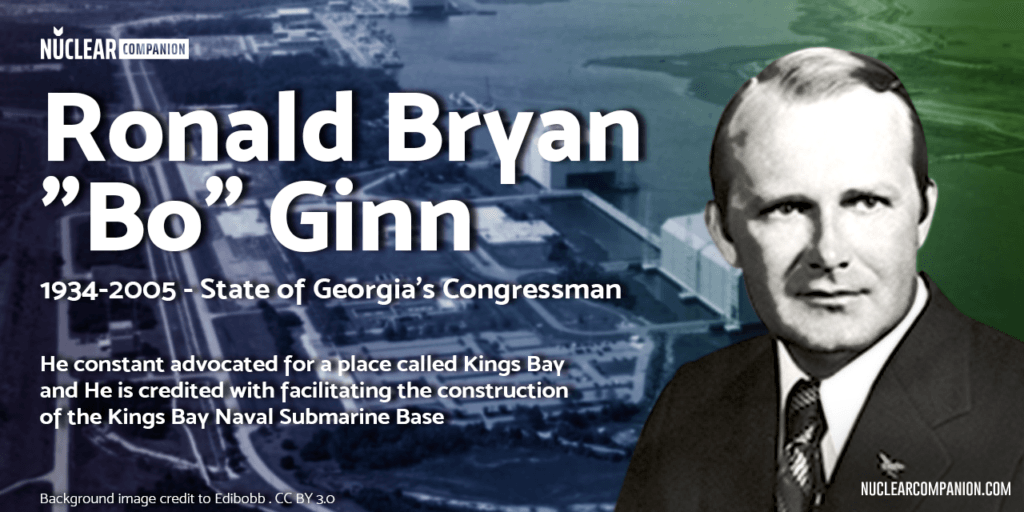

Not everyone was happy with this. So, here is where Congressman Bo Ginn enters the game…

Use Kings Bay or give it up

In 1972, Bo Ginn was elected as Georgia’s 1st district representative to the Congress, and Sam Nunn was elected to the Senate from Georgia. Together they had a plan. Go to Capitol Hill and get the Pentagon to use the base or give it up.

In 1974, Secretary of the Army Howard Callaway declared Kings Bay to remain under Army control. This occurred even though Congressman Bo Ginn requested the Army to re-evaluate their need for the facility.

Despite Ginn’s remarks on the decreasing use of Kings Bay, Callaway stated that it was still of strategic importance. Mainly, as we said earlier, in case of a war erupting in Europe.

Kings Bay, then, could not serve commercial purposes unless the leasing company was willing to agree with the Army requirements.

These requirements were fairly unpopular with many commercial companies. Primarily, given that it asked the company to vacate Kings Bay within weeks if the Army needed it.

Even so, the commercial matter would remain under continuous examination. If the military need for Kings Bay diminished, the Army would consider turning it into a commercial zone. All that without the strict requirements that they decided to keep imposing as of 1974.

But as Ginn’s efforts with the U.S. Army made little progress, he found an ally in the U.S. Navy.

The timing couldn’t have been better …

A whole new role for Kings Bay

Relocation from Spain

Several years later, the United States entered into a diplomatic agreement with Spain. The treaty between the two included the relocation of a squadron of Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarines from Rota, Spain.

In the early 1960s, ballistic missiles launched from submarines had a limited range. These were the Polaris missiles with a published range of 1,200 nautical miles.

So, the U.S. government decided to locate these submarines in bases overseas. In exactly two bases, one in Scotland, and the other at Rota. In exchange for the right to use these bases, the US had agreed to provide aid in various forms.

However, by the end of the 1970s, Spain’s politics had changed. Dictator Francisco Franco, who supported the U.S. military aid treaty, died in 1975. This caused quite strong opposition to the agreements, which before could not be expressed freely, to find its way into the renegotiation of the treaties.

The US found, from a logistics and from a support point of view, preferable to operate those submarines from CONUS bases to divorce itself from the variabilities of the situation. Spain had changed its point of view and at some great expense, it caused U.S. SBBNs to leave.

Now, where in the continental U.S. could the U.S. Navy relocate a Submarine Squadron?

A New Home

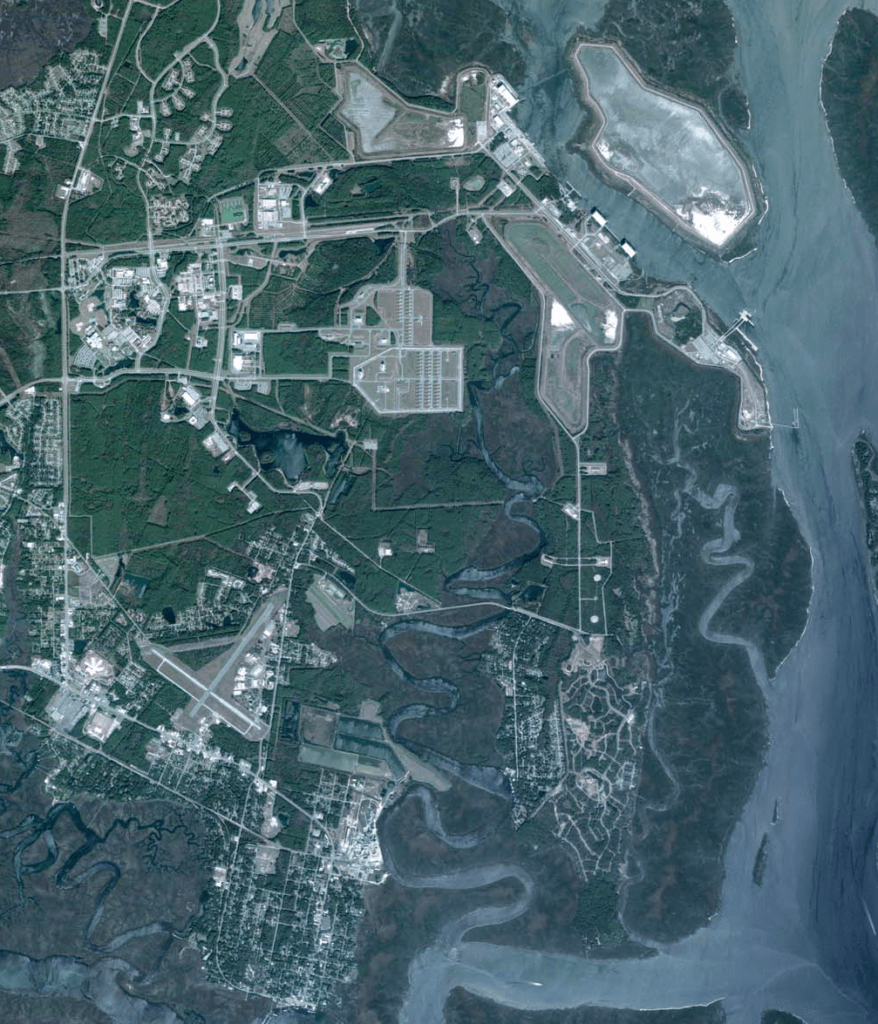

Around 60 sites were considered, and on Jan 26, 1978, the Navy announced their destination. The submarines would move to Georgia. And yes, consequently the navy began to transform Kings Bay into their new submarine base.

Thus, MOTKI was to serve as a support base for the relocated squadron, with tender service facilities rather than shore-based ones. An Army/Navy study, done in May 1977, determined that joint use of Kings Bay was feasible.

The Army was to operate two ammo-loading terminals. The Navy, for its part, was to house up to two squadrons of submarines if tender-based facilities were used.

However, the Navy had long-term plans to use Kings Bay as a base for larger Trident submarines. This demanded shore facilities as well as tender-based ones. Both things were incompatible with the Army’s usage of the base.

As such, when Kings Bay began to house Trident submarines in 1980, the Navy had to pay $21.5 million to the Army for building a new terminal in Earle, New Jersey.

Transition to the Navy

In Jan. of 1978, a group of naval personnel established their office in the Army headquarters at Kings Bay. The official transfer of Kings Bay from the Army to the Navy did not occur until July 1st of the same year.

On that day, Robert Sminkey raised the national ensign and changed the sign for the terminal to “Naval Submarine Support Base Kings Bay”. He was a 30-year naval veteran Commander with a distinguished Navy career. That day with him were 37 sailors and civilian employees.

As the support base’s first commanding officer, Sminkey came to transform Kings Bay. No longer needed as an Army terminal, it was about to become a functioning naval base. It needed to be capable of handling the returning squadron of submarines.

Sminkey, as the person in charge, received the Kings Bay terminal in its entirety.

At the time of the transfer, MOTKI featured one 2,000-foot-long wharf as well as three buildings in the vicinity of the wharf. It also had 47 miles of railroad track and a cluster of temporary buildings four miles away at the main gate. The Army used them for administrative purposes.

Sminkey’s first task would be to establish basic naval infrastructure at the terminal. He was meant to make several changes in order to make it more suited as a submarine base.

Nonetheless, what comes next is all part of the larger story. We will continue with it in the next article of the Kings Bay series.

Now It’s Your Turn

I hope you enjoyed this article.

Now I want to turn it over to you: did you know Kings Bay’s History before the U.S. Navy’s arrival?

Let me know by leaving a quick comment below right now.

Fort Stewart provided support services to the Army activity there at Kings Bay when 81st ARCOM had control there . The Post Engineers for Fort Stewart provided engineering support, forestry, fish& wildlife and local contracting oversight in that period of time when the USAR was there . 3220 USAG had a wartime mission of becoming the garrison staff and running base operations for not only Kings Bay but also Fort Stewart . In the 1970s, the 81st ARCOM’s CG would assume command of Fort Stewart after the regular army’s 24th ID had mobilized and deployed downrange .

My late Father was the Deputy Post Engineer from the late 60s until his retirement in the mid 90s for the Ft Stewart/Hunter AAF complex. Part of his mission included support and oversight of the 81st ARCOM facilities in the southeast US (including the Kings Bay facility as well as the Army Reserve Centers in Georgia and Florida)

So as a kid, it was a real treat for me to get to see the old Liberty Ship and the LARCVs training at Kings Bay when I got to go with him on a Saturday trip down there many years ago.

The base at Rota was not made unnecessary by the Poseidon weapons system. Draw a quick range arc of 2500 miles and see how much of the former Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact was covered leaving Rota. Now do the same from Charleston SC and you get a big fat zero %. Rota was also an invaluable warm water refit site for the boats attached to CSS 14 in Holy Loch, enabling their crews to get painting done. Since the requirement for a fixed number of active target packages remained constant, the CSS 18 submarines, based min Charleston had to maintain a much higher speed of advance to reach their assigned patrol areas. Increased speed means faster use of nuclear fuel, resulting in more refueling overhauls, making the cost of losing Rota higher than the cost of keeping it. It also insulted the Spanish. Dumb move all around

Thanks sid for commenting. I have to agree with you that the withdrawal of SBBNs from Rota was not related to the Poseidon or Trident missiles’ capabilities. The new political situation in Spain and Spain’s changing point of view during the renegotiation of the treaties was more to blame. Updated accordingly.

It was a long time ago but I’m sure I was one of the Reservist at MOTKI the summer of 1973 – and a couple of other years in the 70’s (I left the Reserves in Feb, 1978). I was attached to the 32nd Transportation (stevedores) in Tampa. MOTKI was a desolate place. Campaign tents in the swamps. Didn’t seem like anyone else was there on the wharf but us and the ship’s crew. Though we did share the swamp with other units. Don’t remember them being Army Sailors – were some Green Berets (?). Sorry for sounding like a Bettle Bailey type, but you mentioned that the Reservists learned to load/handle ammunition. We ONlY loaded and unloaded, many many times – concrete jersey road barriers. Oh well. Confessing, in 73 I was a personnel specialist for the unit. But in later years I was a documentation specialist, then hatch foreman.

We were told that MOTKI was left over from WWII. So, thanks for bringing out its true history.

Rich Leibson

Army Reserve 2/8/72 – 2/8/78. (PFC to SGT)

Hi Rich, thanks for sharing your experience at MOTKI. Loved the Bettle Bailey reference!

My Army Reserve unit, 851st S&S Co. from Abbeville, Al. and Enterprise, Al. had annual training there in about 76 or 77. Worst place for biting insects that I have ever been. Best I can remember, there were only 2 or 3 permanent buildings on the place. We stayed in GP medium tents but we did have cots to sleep on. Several years later while working as a long distance trucker, I delivered a load of freight to Kings Bay sub base and was amazed at how much the place had changed.

I was one of the very first women sailors stationed on the USS Simon Lake in Kings Bay Georgia. It was very exciting time for me because I was from a very small town in North Dakota, so this was a great adventure! I greatly appreciated your article and it brought back a lot of memories, and it also gave me tons of information that I wasn’t aware of. I would love to be able to go back and view the base now, because when I first went there, it was pretty much just a wilderness. I remember sitting on a picnic table and watching wild boar run by. And I have fond memories of watching the manatees come up to us along the dock. Not all memories were good of course, but it was an adventure regardless. I’m 60 years old now, and I was 19 when I first boarded the USS Simon Lake AS33! Oh what stories that ship could tell, haha! Thank you again for your lovely article and all the time you spent in researching and writing it. Best wishes to you!

Hi Cheryl. Thank you for sharing your experiences. Your memories inspire the team to delve further into Kings Bay’s past. A vol II would cover the years (1979-1985) when the USS Simon Lake was stationed at the base. Best wishes!

Hi Cheryl ,

Where did you work ?

I was only there 2 years ago but one of the first women … June 1980

My father M. F. Martin, Jr owned Blue Star shipping from the mid to late sixties I guess until the Navy took over. He was in business with Ray Forker for a while. They bought a special container ship that could have modular sections added to it. At some point they divided the business and Mr. Forker took the ship and daddy took Blue Star. We spent time during the summers there when I was young.

Peter, thank you for sharing this personal history. If you have any photos from Blue Star you’d be willing to share and are comfortable with them being published here, I’d be honored to include them. Best Regards, Javier