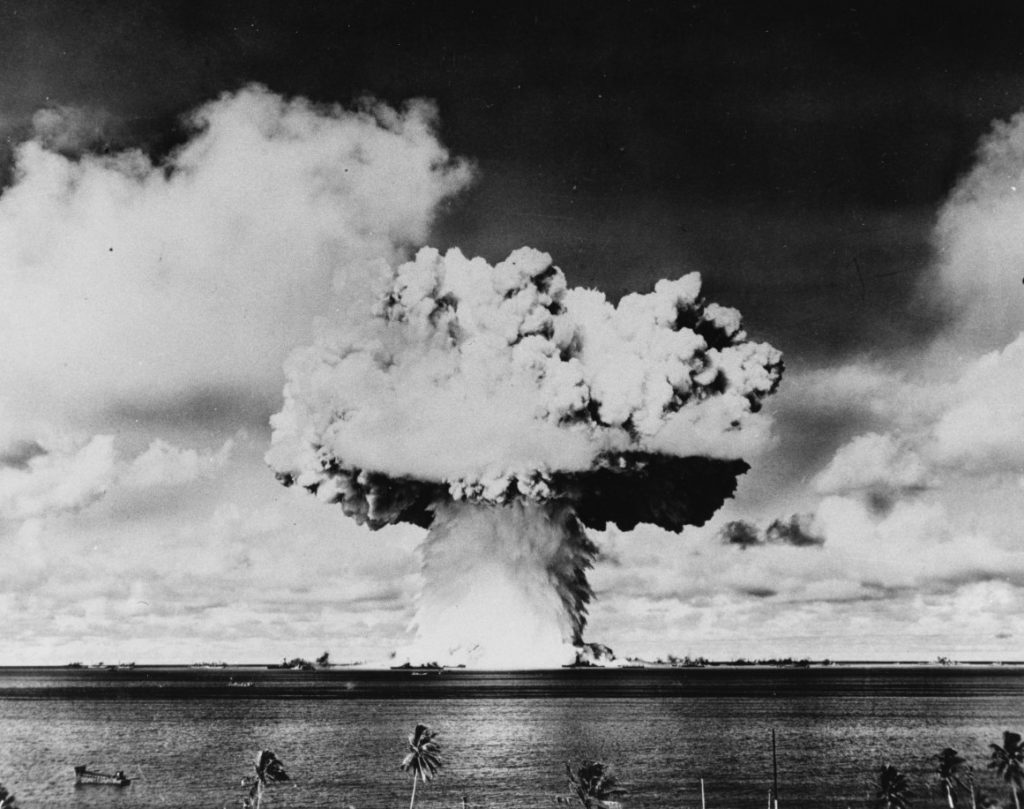

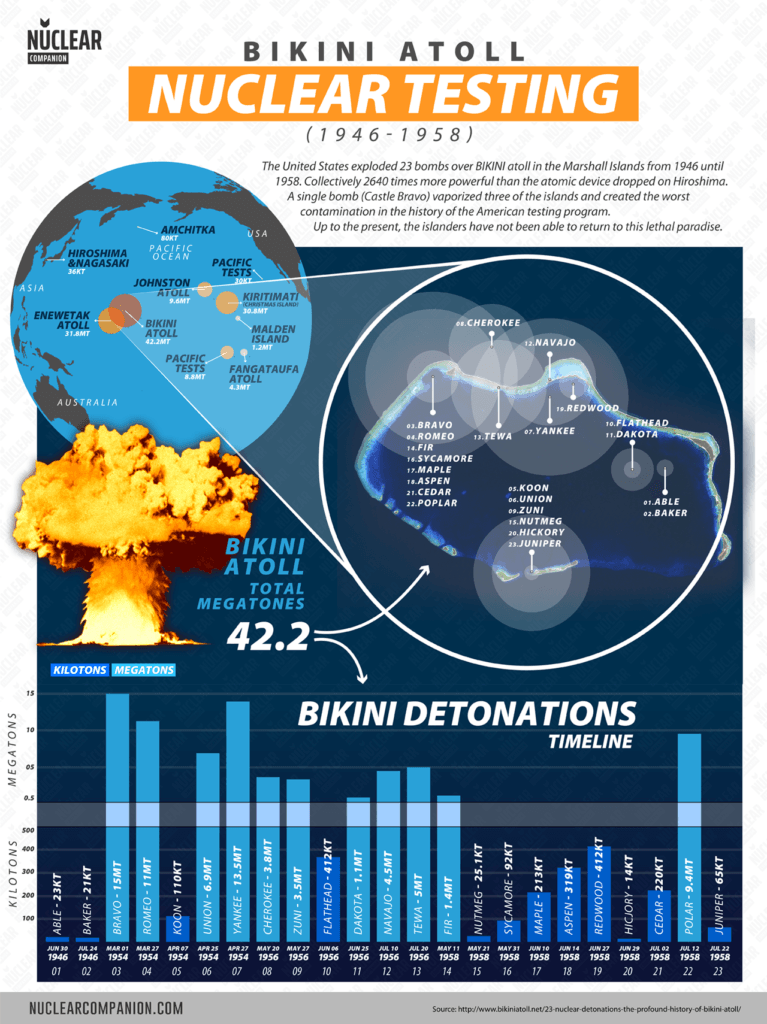

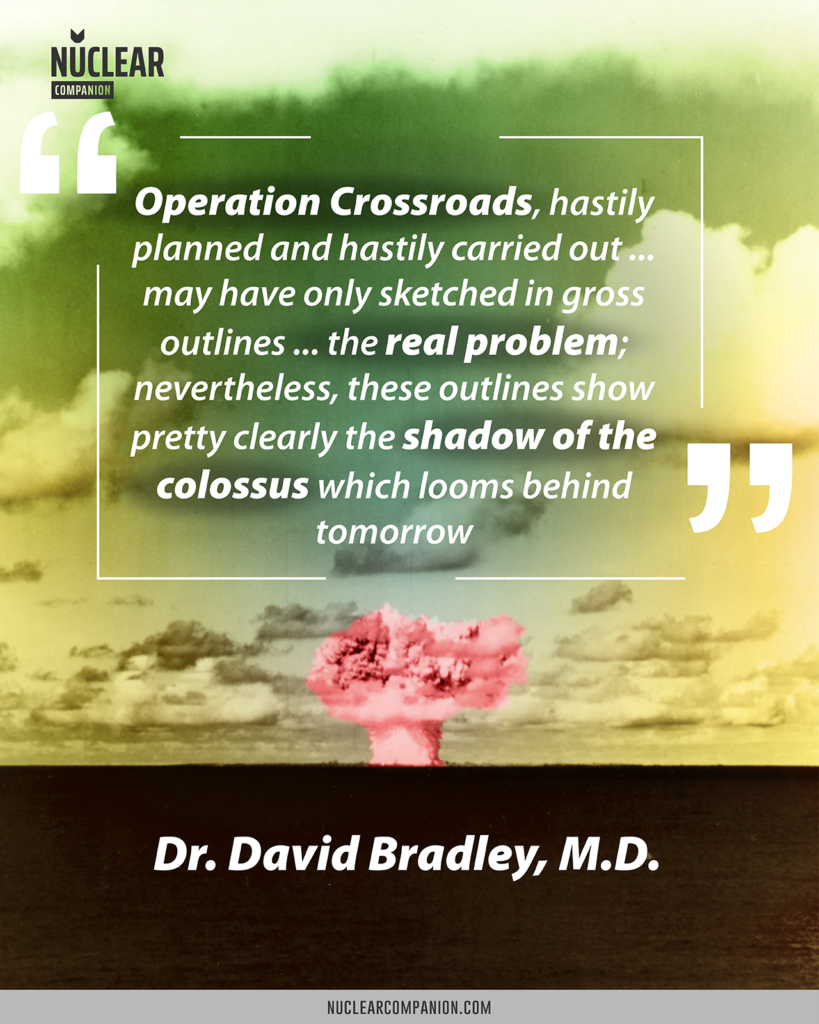

The era of atomic testing began in 1946 with Operation Crossroads. At the time it was the largest U.S. peacetime military operation ever conducted.

41,963 men, 37 women, 242 ships, 156 airplanes, 4 television transmitters, 750 cameras, 5,000 pressure gauges, 25,000 radiation recorders, 204 goats, 200 pigs, 5,000 rats, and the atomic bombs gathered to answer a simple question:

Was the U.S. Navy vulnerable to the new Atomic Bomb?

Introduction

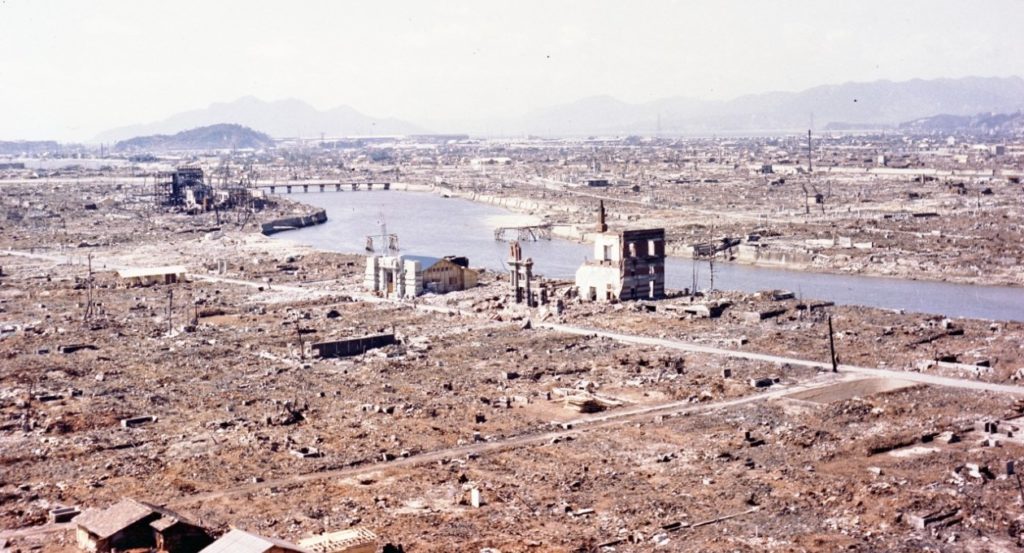

The first atomic bomb exploded on July 16, 1945, but it was covered in secrecy. But then, twice, first at Hiroshima and then at Nagasaki, the whole world perceived that it had entered a new age.

Suddenly, the basis of the existence of many people was altered. If one atomic bomb can destroy an entire city, could it sink an entire fleet? Was the U.S. Navy obsolete? In the postwar world where the U.S. Navy had to secure funding, was it still relevant?

So, this is how the world’s fourth and fifth nuclear detonations in history were born. They were not used for weapons development as the major part of U.S. tests. But to test the effect of a nuclear bomb over a target fleet.

The U.S. Navy expected to sail the target fleet back to homeport to demonstrate the negligible effects of atomic weapons against naval vessels.

In the end, the U.S. Navy was much chastened by the tests, the U.S. Air Force was embarrassed, and Crossroads became the World’s first nuclear disaster.

Its story is what you’re going to learn right now…

The defeated Japanese fleet

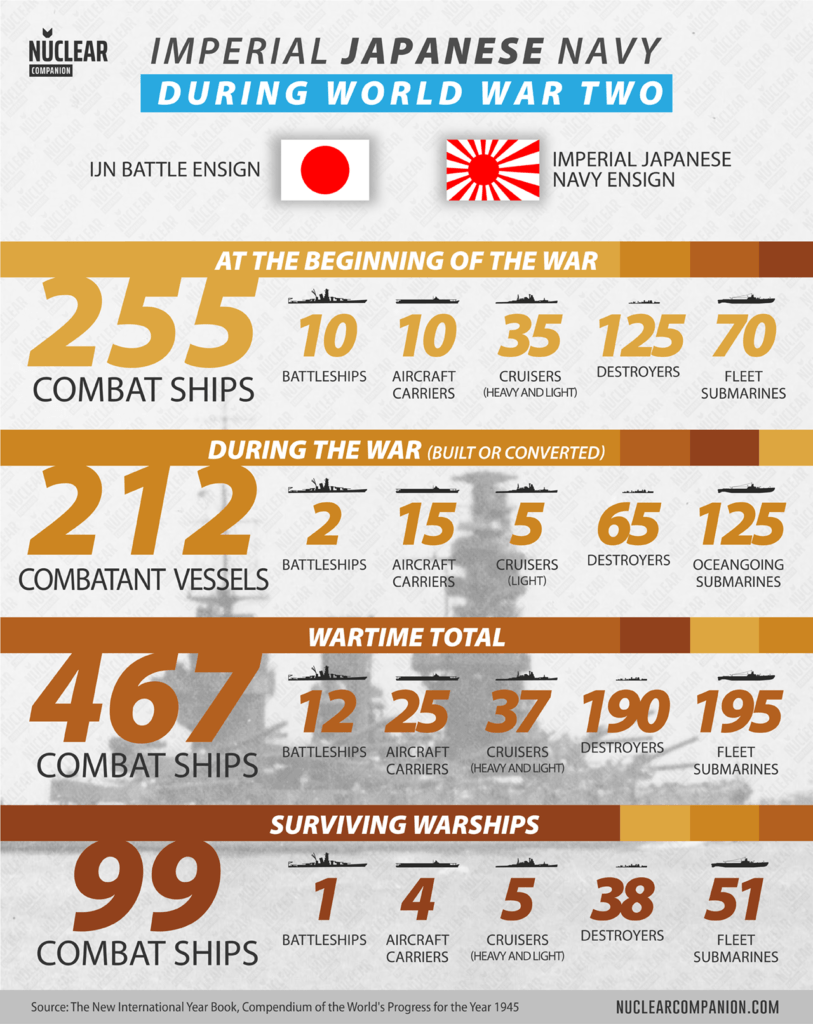

By the beginning of World War 2, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was the third largest navy in the world.

In fact, at the start of the Pacific War:

- It was more powerful than the combined British and U.S. fleets in the Pacific area.

- It possessed the most powerful carrier force in the world.

- It included ten battleships, giving it the third-largest battle line in the world.

- It was at numerical parity with the USN regarding heavy cruisers. These had a reputation for superior size and firepower.

- Its destroyers were formidable opponents and were generally larger than their Allied counterparts and were better armed in most cases.

But, four years later at the time of Japan’s surrender, the IJN was reduced to a shadow of their former glory.

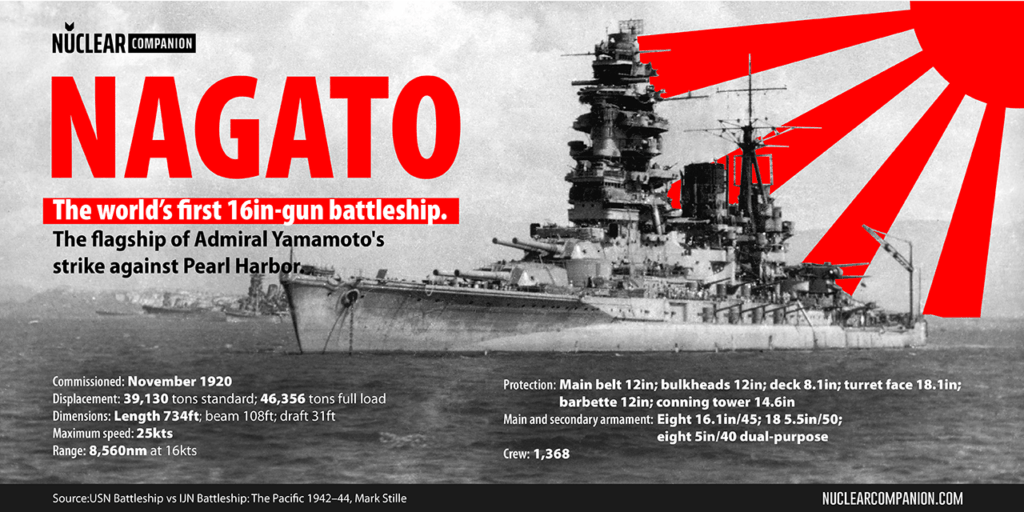

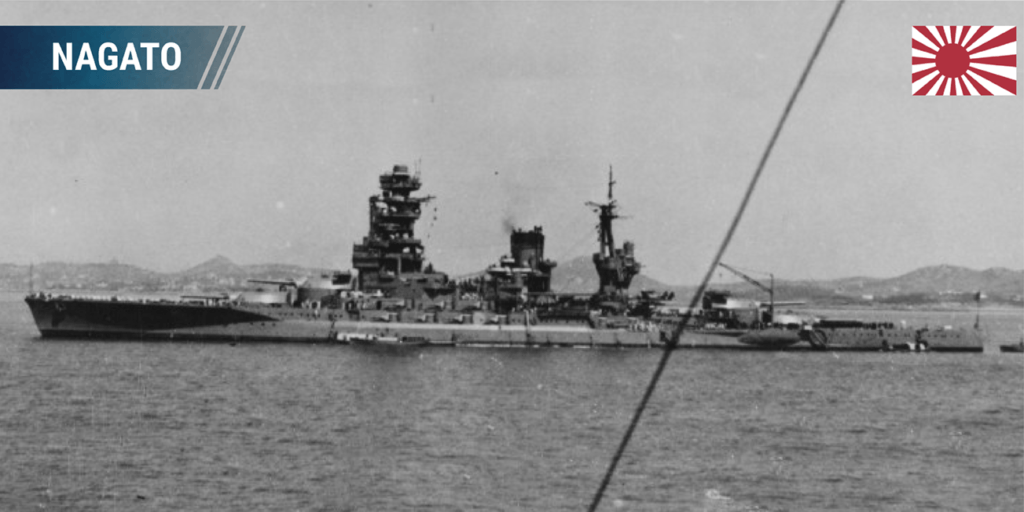

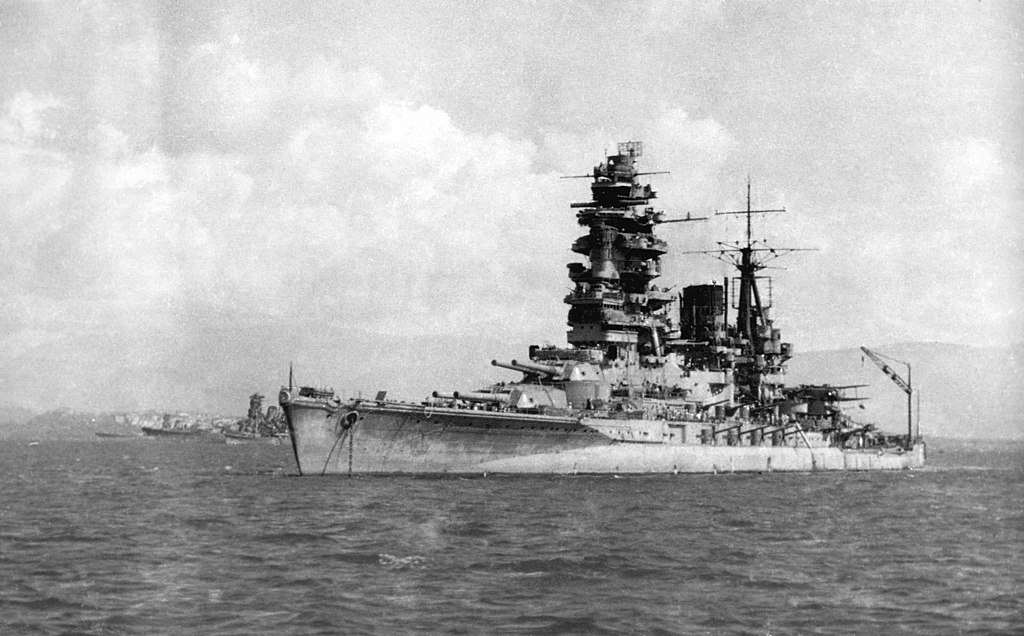

When the war ended, there was only one Japanese battleship still afloat. It was the pride of the IJN: Nagato.

She was the largest and most powerful battleship in the world when commissioned in 1920. And It had been Admiral Yamamoto’s flagship during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Nagato’s last action was the Battle of Leyte Gulf. After that, due to fuel shortage, it was assigned in 1945 to the Yokosuka Naval District. There, Nagato served as a floating antiaircraft battery until the war’s end.

In the end, the Japanese Navy would cease to exist. The 10 large warships would be scuttled and the smaller ones transferred to the United Nations powers.

However, Nagato’s fate would be a different one…

The U.S. Navy at the end of World War II

In contrast, at the end of World War II, the U.S. Navy was the strongest in the world.

In three and a half years the U.S. Navy had:

- Destroyed so much of the Imperial Japanese fleet that it had ended as an organized fighting force.

- Defeated the German U-boat threat during The Atlantic Battle

- Supported the greatest amphibious campaigns in history (MacArthur’s island-hopping)

To achieve that, the U.S. Navy in 1945 had grown to 3.4 million men, 1,200 combatant ships and 40,000 aircraft.

Despite its triumph and strength, the U.S. Navy faced a new threat. Not only U.S. Navy’s ships were vulnerable to an Atomic Attack but the U.S. Air Force had a monopoly on Atomic Weapons.

Also, with the end of the war, the U.S. Navy had to demobilize this enormous military capacity. In September 1945, Secretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal predicted a peacetime navy of 400 combatant ships.

In the end, the war ended leaving the U.S. Navy with such a sense of uncertainty and an obscure future…

Road to Crossroads

But the U.S. Navy would respond quickly to this new threat.

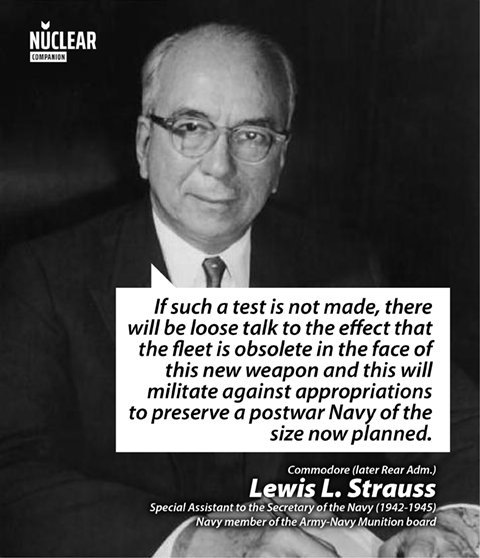

Seven days after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Commodore Lewis L. Strauss sent a memorandum to his boss: James V. Forrestal, secretary of the Navy. Strauss, who was Forrestal’s Special Assistant and a navy member, had no role in the manhattan project. But, he would become later an important figure in the Atomic Energy Commission.

In his message he recommended test ships’ ability to withstand the atomic bomb:

“If such a test is not made, there will be loose talk to the effect that the fleet is obsolete in the face of this new weapon and this will militate against appropriations to preserve a postwar Navy of the size now planned.”

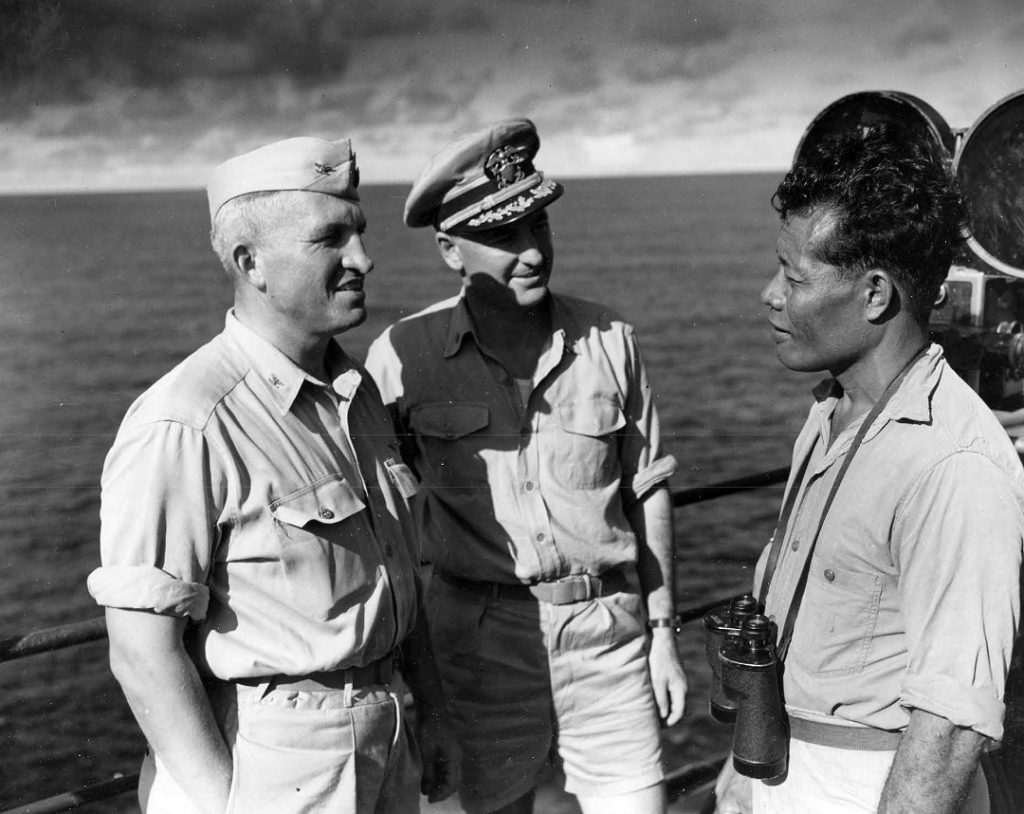

Lewis L. Strauss

Forrestal agreed. But for him, the question was not if the ships could survive against atomic bombs but how the navy could employ atomic weapons. He was sure the U.S. Navy needed its own program of research and development together with cooperation with private university laboratories.

The Sinking of the Ostfriesland (1921)

This was not the first time that the U.S. Navy faced the threat of new technology.

In June 1921, U.S. Army Air Corps general, William “Billy” Mitchell was able to arrange a series of tests of bombers versus battleships off the Virginia Capes. It resulted in the sinking of the elderly German Jutland veteran dreadnought Ostfriesland.

The U.S. Navy had responded to the threat of aviation by incorporating it into its service in the 1920s and 30s.

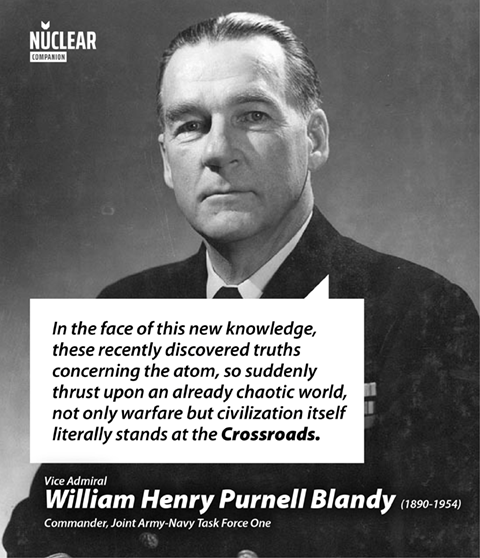

By November 1945, Forrestal had established the Office of Special Weapons (OP-06) under Vice Adm. William H. P. Blandy. Not only had Blandy responsible for developing nuclear energy but also missiles and all other foreseen new Weapons.

But the U.S. Navy atomic worries were only the tip of the iceberg…

The Nimitz proposal

On August 28, 1945, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific (CICNPAC), recommended that the surviving Japanese warships be destroyed.

Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Fleet Admiral Ernest King submitted Nimitz’s proposal to the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). But the JCS had to wait until the return of Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, to take any action. Destroying the Japanese ships was not only of interest to the U.S. but also the Russians, British, and Chinese.

Byrnes was participating in the first post-war conference of foreign ministers in London. He would not return until the 4th of October.

A provocative question

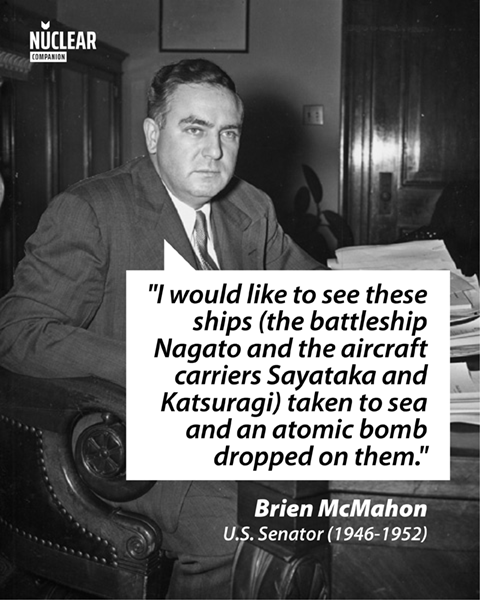

In 1945, Senator Brien McMahon had been in Congress barely a year. But he was an ambitious freshman Democrat from Connecticut. Later, he would better be known for introducing the first bill dealing with atomic energy into the Senate.

On August 25, 1945, during the Annual Jefferson Day dinner of the Connecticut Democratic Party in New Haven, he suggested:

“I would like to see these ships (the battleship Nagato and the aircraft carriers Sayataka and Katsuragi) taken to sea and an atomic bomb dropped on them.”

“The resulting explosion should prove to us just how effective the atomic bomb is when used against the giant naval ships. I can think of no better use for these Jap ships.”

Senator Brien McMahon

McMahon insisted that the Atomic bombs used in Japan did not provide enough evidence of the bomb’s true power. Quickly his voice echoed among several members of the military…

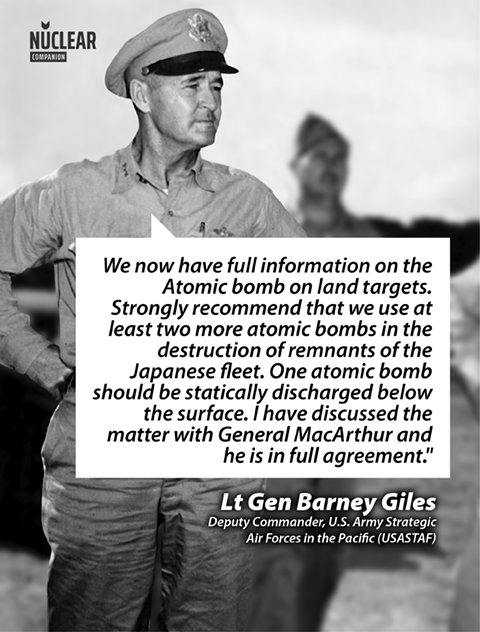

The Giles proposal

On September 14, 1945, Lt Gen Barney Giles, acting Commander of United States Army Strategic Air Forces (USASTAF), echoing Senator Brien McMahon elevates the idea to his superior, General Hap Arnold of the AAF:

“We now have full information on the Atomic bomb on land targets. Strongly recommend that we use at least two more atomic bombs in the destruction of remnants of the Japanese fleet.

One atomic bomb should be statically discharged below the surface. I have discussed the matter with General MacArthur and he is in full agreement.“

Four days later, Arnold raised the proposal to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He proposed the chiefs to determine military requirements for Japanese ships “suitable for future experimentation with conventional bombs, atomic bombs, guided missiles, and other possible new weapons”. Thus, opening these ships for use in tests involving atomic bombs.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff decreed that some of the Japanese ships to be preserved for experimentation. It was to General of the Army Douglas McArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander in Japan, to inventor and report back the status of such vessels. They still have to wait for the Secretary of State James F. Byrnes to return at the beginning of October for a formal agreement.

So, Nimitz’s idea of sinking the remaining Japanese ships became one with Giles’s idea of using them as atomic targets.

On 16th October, after Byrnes’s approval on the plan, Admiral Ernest King expanded the idea. He urged the test to be enlarged with U.S. surplus warships and suggested using the Carolina Islands as the test site.

Fortunately for them, the American, British, Chinese, and Russian governments got to an agreement on 31 October. Japanese remaining combat ships would be destroyed. Only thirty-eight destroyers would be divided among the allies.

On that same day, General Arnold gave his support to Admiral King’s idea of 16 October. With this agreement, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directs its planners (Joint Staff Planners) to create a plan to present to the president. This plan should be an outline of the type of tests, requirements, and recommended the agency to implement the tests.

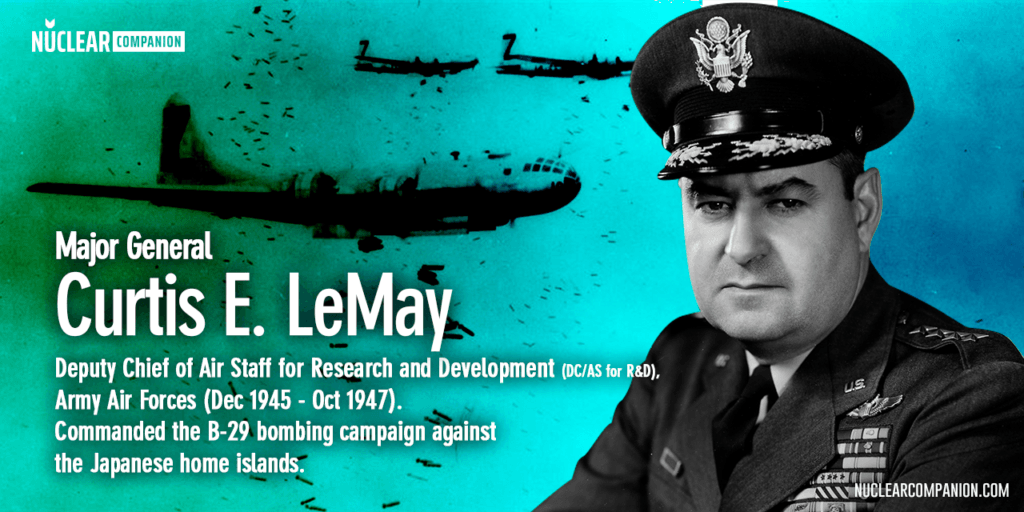

On 9 November the Joint Staff Planners turned over their work to a sub-committee of experts. This sub-committee chaired by Major General Curtis E. LeMay would show the first conflicts between the U.S. Navy and the Army Air Forces.

Sidenote. Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the moment were: General H. H. Arnold, General G. C. Marshall, Admiral E. J. King, Admiral W.D. Leahy

LeMay Subcommittee

The “LeMay Subcommittee” was key in the planning phase of Operation Crossroads. It had the job to coordinate and decide on critical aspects of the scheduled tests, including whether or not target ships were to have fuel and ammo. Appointed by the Joint Chiefs’ Joint Planning Staff, it was also the subcommittee doing to chose those to be in command of the operation.

- Major General C. E. LeMay (Steering Member)

- Brigadier-General W. A. Borden

- Colonel C. H. Bonesteel

- Captain G. W. Anderson, Jr. (Navy)

- Captain V. L. Pottle (Navy)

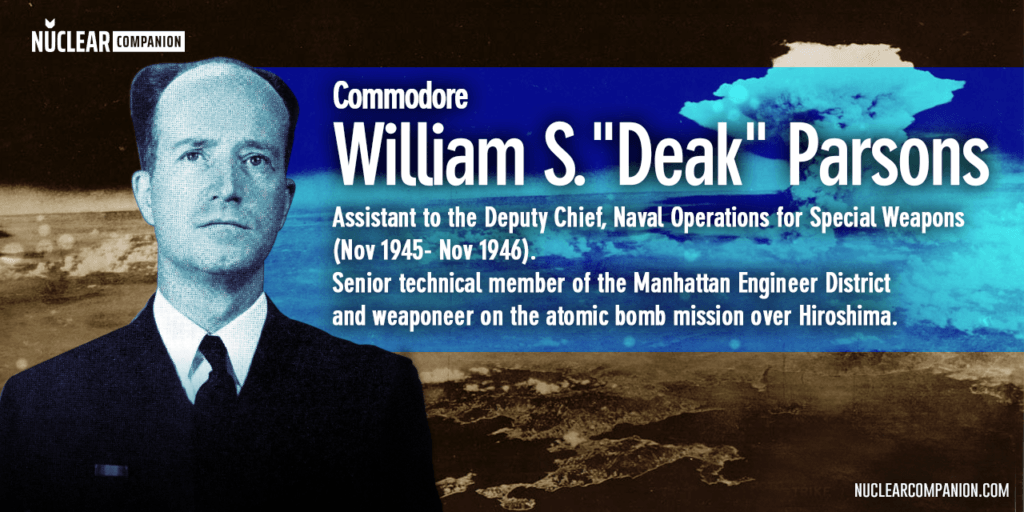

- Commodore (later Rear Admiral) W. S. Parsons

In front of the subcommittee was Major General Curtis E. LeMay from the U.S. Air Force. Representing the U.S. Navy, on the other hand, was Commodore William S. “Deak” Parsons. He was the weaponeer inside aircraft Enola Gay when the nuclear drop on Hiroshima took place.

But aside from the technical aspects of the operation, Parsons also had the responsibility of defending the U.S. Navy’s interests. The committee became part of a sort of dispute between him and LeMay himself.

LeMay wanted the U.S. Air Force to have control as they were providing the only capable aircraft of delivering a nuclear bomb at that time. He even went to met with U.S. President Truman to express his concerns about the operation.

Parsons, for its part, argued that despite the U.S. Air Force’s relevant role, it was the U.S. Navy who held most of the operation’s assets. Not to mention it also had officers expert in the nuclear field.

Parsons wanted the U.S. Navy to have the last word on making the decisions for the test. In this sense, the U.S. Navy had the Navy Atomic Bomb Group, which would take care of the preliminary arranges for the operation.

In Dec., LeMay proposed General Groves, previously head of Manhattan Project, to be at the command of the operation. Joint Chiefs, nonetheless, were fond of having a Joint Task Force One commander from the U.S. Navy.

Joint Chiefs agreed on Parsons in that most of the assets and human resources for the operation were indeed from the U.S. Navy. As such, they chose, on Parsons’ recommendation, Vice Adm. William H. P. Blandy for the position.

But this wasn’t the end of the dispute. The U.S. Air Force wanted to be in charge of the preparation, deployment and subsequent scientific analysis of the nuclear bomb’s effects. In this last regard, they wanted the bomb to be tested on U.S. Air Force materials.

That very same month, the U.S. president recommended the Congress to unify the armed services as a way to make them more flexible. As cooperation became an obligation, the dispute was settled.

On Dec 22. the Joint Chiefs received the test outline from the Joint Planning Staff. There were going to be three tests, each at a different explosive plain:

- One would be dropped from a plane. This would have as target all sorts of navy boats, arranged to receive different grades of damage. In this way, the army could reliably measure the damage at different ranges and to kind of targets. They would be able to measure the damage from the explosion itself and its radioactive effect.

- Other detonated at ground level and the third and final detonated thousands of feet underwater. The second and third explosions, for their part, had as objective to show ships’s reaction to them. Mostly, to measure at what range did ships sank or became inoperable. To identify these damages, ships would be inspected trough divers, and later on, on a drydock.

Lastly, the committee requested Joint Chiefs to appoint a military evaluation board for the operation. It was integrated by members of the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy, as well as participants of the Manhattan Project and civilian scientists.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the report on 28 December.

The outline of the testing was ready. It was time to execute it.

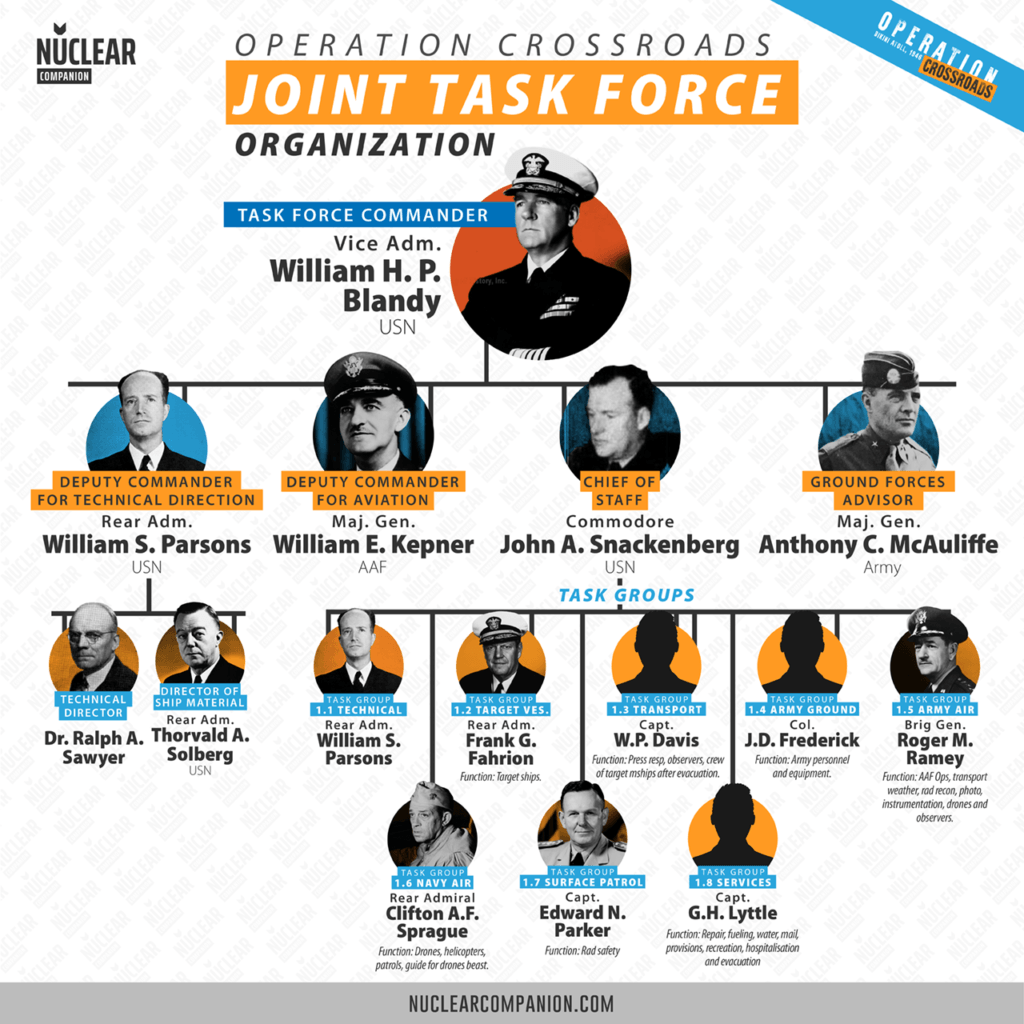

A Joint Task Force

On Dec. 29, 1945, President Truman appointed Vice-Admiral W.H.P. Blandy, USN, Commander of the Join task Force. This force would be in charge of executing the testing plan. Due to the importance of this operation, the Navy officer was to answer directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

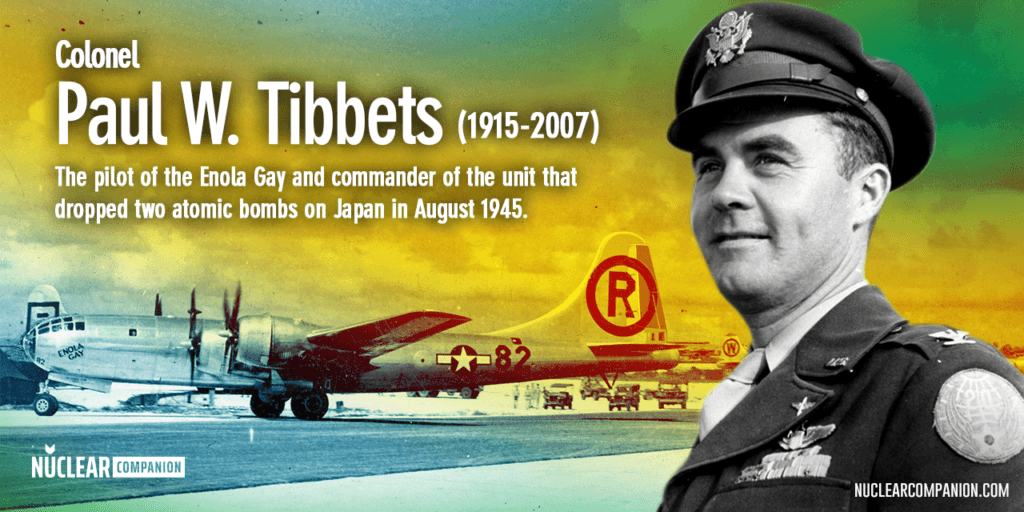

Alongside Blandy, two other names joined as well for advising him on technical subjects. One man from the U.S. Navy and another from the Air Force: Commodore William S. Parsons and Air Force Colonel Paul Tibbets Jr.

Preparations started immediately with namings for the main staff positions just a few days later. Brigadier General William E. Kepner joined first as Deputy Commander for Army and U.S. Navy Aviation. Brigadier General Thomas S. Power followed as Assistant Deputy Commander.

On Jan. 5, Blandy submitted his plan for the operation to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This was but a week after his appointment and even before the operation itself had presidential approval.

In his plan, Blandy suggested the name “Joint Task Force One” for his operational force. Likewise, he proposed naming the operation “Crossroads”. The name corresponded to the operation’s transcendence as the first public nuclear weapon test.

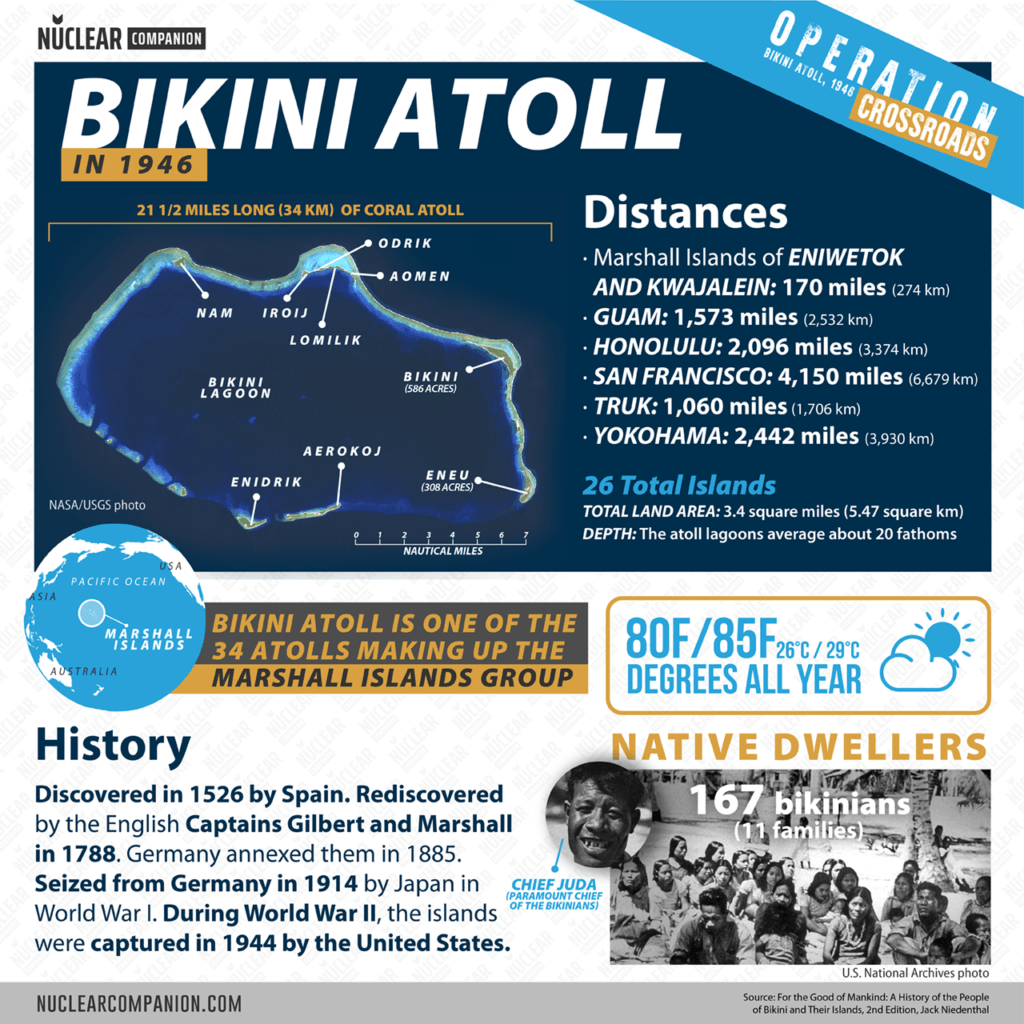

In choosing the dropping location, Blandy viewed the Marshall Islands as a sound choice. It was an isolated U.S. trust territory far from any considerably populated area that the bomb could compromise.

Within the Marshall Islands, Blandy studied Bikini Atoll as the ideal location for the explosions. For one thing, the local population was barely 200 people, so relocating couldn’t be an issue. However, this would prove to be more troublesome than initially considered.

Besides, Bikini atoll’s lagoon was perfect for harboring Joint Task Force 1’s ships. Not so much for aircraft landing, though. Still, close atolls Kwajalein and Eniwetok were large enough for fitting the B-29s and drone aircraft B-17s for the test.

Now that Blandy had his staff and place, it was time for him to get into the details of the two initial explosions.

Blandy alphabetically named the tests “Able” and “Baker”. The first one would be a dropping; the second, a detonation at ground level. There was also the possibility of a third one, named “Charlie”.

Blandy’s plan recommended a dropping altitude of 30,000 ft for Test Able. Falling from there, the bomb would explode 600 ft before reaching the ground.

In this regard, some suggested using a balloon for greater precision in a mid-air explosion. An idea that fell through, given that the consensus was in favor of a B-29, invariably the first choice for the task.

For both planned tests, the target fleet would respect a radial formation around the detonation point.

On Test Able, an aircraft carrier would act as the target ship for the dropping. The carrier, for its part, would be surrounded by the other main, largest ships. The rest of the fleet would be mixed at different distances to test the effects of the bomb on each type of ship at different distances.

Moving to Test Baker, Blandy suggested attaching the bomb to a landing ship tank. This ship would act as the center of the target array. As for arraying the target fleet, Blandy had a few ideas.

- Anchoring them using a ground tackle;

- Using the atoll’s neighboring reef,

- To let them drift away while keeping them together with towlines. In this case, a bark could carry the bomb with the help of the wind.

Test Names

U.S. nuclear weapons tests were originally named in accordance with the international phonetic alphabet (most commonly used by U.S. military and federal agencies).

This practice eventually led to some confusion: there were four “Able” shots (in Operations CROSSROADS, RANGER, BUSTER-JANGLE, and TUMBLERSNAPPER), four “Baker” and one “Baker-2” shots (Operations CROSSROADS, RANGER, BUSTER-JANGLE, and TUMBLER-SNAPPER), two “Charlie” shots (Operations BUSTER-JANGLE and TUMBLER-SNAPPER; a “Charlie” shot planned for Operation CROSSROADS was canceled).

Starting in 1953, to avoid even more confusion in the future, shots were given unique names that were not based on the international phonetic alphabet.

For collecting explosions’ data, ships had close to 30,000 measuring devices. Much of them were modified or specifically designed for the test. Also, 6,000 test animals were to board different target ships.

The operation involved studying the effects of nuclear bombs on different materials as well. In this way, Blandy required the Army force to use Bikini’s coast and target ships’ decks for arranging their equipment and weapons. Still, aside from this matter, the Army didn’t play a large role in Crossroads.

The Air Force and U.S. Navy, for their part, saw on Crossroads an opportunity for testing both their hardware and themselves.

Five days after Blandy presented his plan, President Truman confirmed Operation Crossroads. The next day, the Chiefs of Staff approved Blandy’s plan.

JTF-1 Organization

Blandy’s next step was to build his staff with scientists and members of the three US Army forces.

By Jan. 11, JTF-1 enjoyed its own headquarters inside the U.S. Navy’s main facilities in Washington, DC. Among the first to secure their spot in the force were Kepner and Parsons, who had helped Blandy in his plan. Kepner became Deputy Commander for Aviation; Parsons, Deputy Commander for Technical Direction.

Major General A. C. McAuliffe completed the main staff list. He became Deputy Commander for Ground Forces.

The Chief of Staff of the force was Commodore A. J. Snackenberg. He had four assistants chiefs of staff:

- U.S. Navy Captain Robert Brodie, Jr., Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel.

- Army Brigadier General T. J. Betts, Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence.

- U.S. Navy Captain C. H. Lyraan, Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations

- Army Brigadier General D. H. Blakelock, Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics.

Joint Task Force 1 divided its deeds into eight groups, each with its own subgroups, accounting for a total of thirty-nine units. The eight main groups were Technical, Target Vessel, Transport, Army Ground, Army Air, Navy Air, Surface Patrol, and Service. Blandy and his three deputies had full control over these groups.

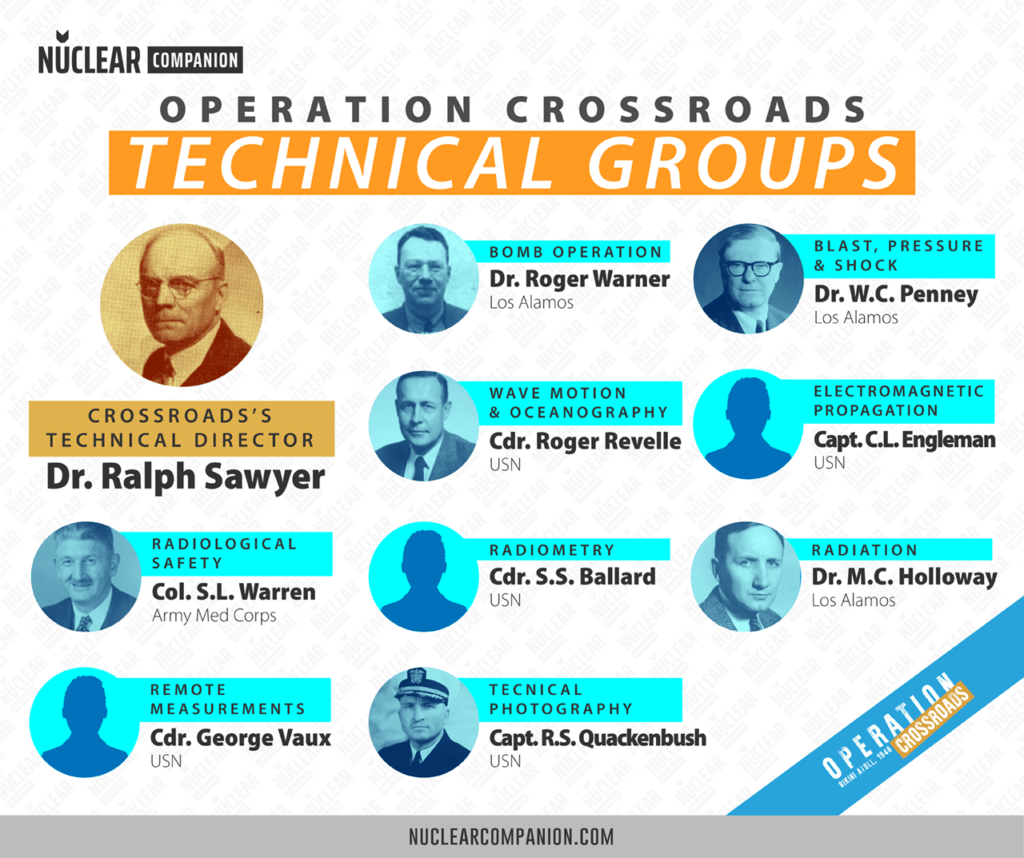

As Technical Director of the operation, Parsons incorporated U.S. Navy Roar Admiral T. A. Solderd and Technical Director Dr. R. A. Sawyer.

Sawyer chose a staff of seven assistants composed mostly of naval officers. He divided his office into nine groups, accounting for a total of thirty-two technical projects.

Considering the resources involved, Crossroads was the greatest scientific experiment at the time. In this sense, Joint Task Force 1 was responsible for the presence of 550 scientists in Bikini.

The Target Fleet

As preparations advanced, the target fleet arraying brought a lasting conflict between the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Navy.

For the U.S. Navy, proper recording of the explosions required setting instruments inside the target ships. For this method to work, arraying would have to secure some of the ships and let them survive the tests.

The U.S. Air Force, for its part, considered that the whole fleet had to be within a thousand yards from ground zero. A greater distance would compromise the 30,000-ft dropping, as missing the central target was a possibility.

The discussion between parties didn’t take long for reaching a dead end. Forces went to mediation. The Military Advisory Board deliberated for two months throughout different plans and solutions.

On Feb. 21 Blandy presented a new array model, (the fourth) to a troubled U.S. Air Force. Of a total of ninety-three ships, twenty-three of them would be within 1,000 yards from ground zero. Under this configuration, not all ships would suffer identical damage.

LeMay recommended the U.S Air Force to go with this plan, which wasn’t the last cause of disagreement between these forces.

During this stage, the target ships’ fuel and ammunition levels arose different views as well. In preserving the ship’s instruments, the U.S. Navy wanted to maintain the levels of these goods at a minimum.

On the contrary, the U.S. Air Force asked for fully loaded vessels. They wanted to know the effects of the explosion on as many materials as possible. Eventually, not all ships were fully loaded with fuel and ammunition.

Additionally, the marking of the target ship was still to be resolved. It had to be striking enough for the bombardier crew to see it from 30,000 ft of altitude. Looking from there, the ship at the center of the fleet would be hard to spot in the middle of the ocean.

All agreed that the best solution was painting the ship, USS Nevada, orange with white spots, while also fixing a searchlight.

The Movement of the Task Force Headquarters to Forward Area

Blandy’s plan also acknowledged the public interest. He encouraged inviting civilians to watch the nuclear explosions from the U.S. Navy designated points.

Initially, the U.S. government granted 200 invitations for observing the tests from Task Force’s ships. Blandy, nonetheless, concluded that the ships they initially had for hosting them wouldn’t be enough. Neither especially comfortable.

At this point, Nimitz had the idea of employing three additional ships for hosting guests. These additional ships made space for double the visitors and congressmen.

A total of sixty congressmen were to see the test. Plus, four additional congressmen moved to Bikini to work at the Evaluation Board Crossroads.

But so many congressmen moving from the mainland U.S. was surely going to affect the congress agenda. Especially, as Congressional elections were not far away.

At least that’s what Texas Speaker Sam Rayburn thought. He let the president know of his concerns, and a cabinet meeting took place on Mar. 22 for discussing the subject. Despite Blandy wanting to go with the schedule, the president agreed on delaying the test from May 15 to Jul. 1.

The news was ill-received by those involved in Crossroads. Joint Task Force 1, in the middle of their moving to the Pacific, had to wait until May to do so.

On May 8, JTF-1‘s staff boarded USS Mount McKinley, Blandy’s flagship, in San Francisco. Before reaching Bikini, the ship made a stop at Pearl Harbor the fourteen for officials to join. Among them were Blandy, Kepner, McAuliffe, and Parsons.

Shortly after boarding his ship, Blandy replaced the ships’ flag, then Snackenberg’s, for his own, assuming command of the Task Force.

The ship spent a whole week in Hawaii before departing. There, they made a proper check of all the equipment on the ship. They reached Bikini in Jun. 2. Able day was still a month away; yet, as we will see, they still had much work to do.

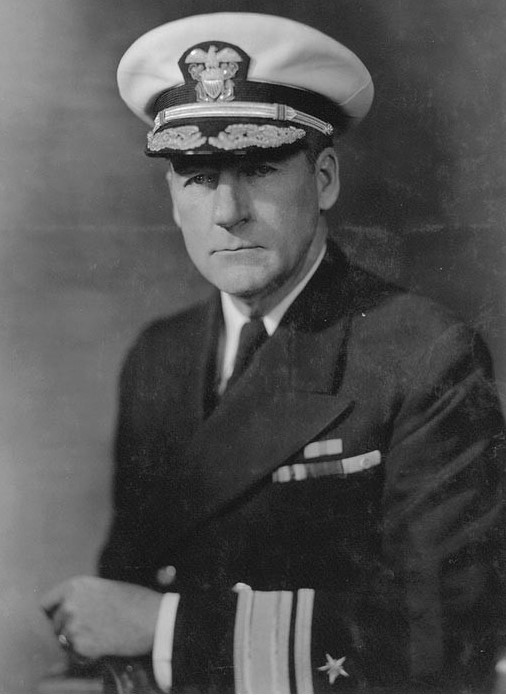

Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy (1890-1954)

The face of Operation Crossroads was Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy. Native from New York City, prior to Crossroads he had a long record on the U.S. Navy showing for his merit to achieve this position.

Blandy’s career started in Annapolis’ Naval Academy, where he was nicknamed “Spike” by his peers. During these days he excelled at fencing and graduated as Honor Man in 1913.

The very next year Blandy commenced his service in the U.S. Navy taking part in the occupation of Veracruz and in World War I subsequently. By 1935, Blandy was commander of Destroyer Division 10. In May next year, he made it into the Division of Fleet Training for the Chief of Naval Operations as Head of the Gunnery Section.

In Dec. 1938, Blandy became commander of the battleship USS Utah. By then, Utah was already retired from regular service and served as a radio-controlled target ship, used in many air bombing tests.

In 1941, Blandy was appointed chief of the Bureau of Naval Ordnance, an administrative position he kept until Dec. 1943. Shortly after, he joined the Pacific Fleet commanding Amphibious Task Group until Jul. 1945.

As a combat leader, Blandy was a very organized strategist. His first fighting operation was the Battle for Kwajalein (Jan. 19 to Feb. 6, 1944). During this time, he also participated in the capture of Peleliu and Angaur, as well as in the occupation of Ulithi Atoll.

Later on, Blandy became commander of the Amphibious Support Force. For his participation in the assaults of Iwo Jima, Okinawa Gunto, and Nansei Shoto the U.S. Navy awarded him Gold Stars. He also fought in the Kerama Islands, near Japan‘s main islands.

By July 1945, Blandy was in command of all cruisers and destroyers on the Pacific. Following that year, he became Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Special Weapons).

Throughout his career, Blandy served on different U.S. Navy fields both on land and sea. It was thanks to his experience in naval ordnance and construction, though, that he was appointed for Operation Crossroads. After the operation finished, Blandy was promoted to Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet(CINCLANTFLT).

Bikini: Land of Coconuts

The Testing site

Let’s take a look now at where the tests took place and how the U.S. Navy chose this location.

The Trinity test, the first nuclear test, and the only one before the Japan droppings took place on U.S. soil (New Mexico). However, now that the war was over the authorities could become pickier on where to perform their new testings.

In this sense, the U.S. Navy started to look at other factors like the weather. The wind had to be predictable for avoiding a potential nuclear deviation.

At the same time, the place had to be isolated enough to not provoke a fallout on continental U.S. territory. Also, stormy sites were to be avoided for personnel to work properly.

This reduced the possible places greatly. Not to mention that B-29s, the only aircraft capable of delivering the bomb, could only work under 1,000 miles from one of their bases. In this way, the Pacific was where the U.S. Navy looked for the ideal scenario.

For their part, Pacific atolls, ring-shaped coral islands formed by the erosion of former volcanoes, were ideal. In their inner lakes, the U.S. Navy could gather and anchor the target ships before the tests. It had to be not merely a Pacific atoll but one part of US territory.

Lastly, the location could not have more than a small local population who could be moved away without much trouble.

With all these factors taken into account, Admiral Blandy announced the election of Bikini Atoll for the tests in Jan. 1946. Far from Hawaii and any Asian big city, Bikini Atoll was the ideal place.

Located in the Marshall Islands, it had merely 167 inhabitants at the time. As such, moving them to another close atoll wouldn’t be a problem, at least logistically speaking.

A little history

But how did these islands came to the U.S.’ hands?

The Marshall Islands had more than one abroad ruler, starting with Spain, and later on, Germany. At the beginning of World War I, Germany lost possession of them to Japan, who kept them de iure since 1919 and until the end of World War II.

Japan kept a trade route and development of the islands until the thirties. In that decade, the Japanese began to adopt a fortifying policy closing the islands to the exterior world.

World War II saw locals became laborers helping in the Pacific defense against the US by turning Bikini into an outpost until the end of the war. Bikini atoll, then, alongside the rest of the Marshall Islands, passed to US hands. The US rapidly took care of the local population with supplies, public services buildings, and a new form of communal government.

As such, Bikinians had they overlord country in high regard, at least enough for consider it their Irioj Alap, that is, their highest chief. The trust was mutual, and the U.S. Navy was surprised by the fact that they didn’t even have a figure for murder punishment as there were not such.

Bikini’s name

Bikini´s name origins from the time it was part of German New Guinea. The german word Bikini derives from the native name “Pikinni”. Pik means “surface” and ni means “coconut”. This “land of coconuts” refers to the huge groves of trees visible on the horizon as one approaches the atoll.

Meet the Bikinians

But who were these people?

The small Bikini population was led by the twelve heads of the main families, directed as well for a general ruler.

At the time of Operation Crossroads, such position was held by a dark-skinned, muscular middle-aged man called Juda. Juda, of bad teeth and short height, rightfully held this position as male heir of the first conqueror of Bikini named Larkeloft.

On the other hand, Bikinians were Protestants. In the 19th century, they were visited by New England missionaries resulting in natives turning into their religion.

They were not Catholics despite the Spanish reached the islands first in the 16th century. Strange enough, Catholicism, was the faith kept in the Caroline Islands, despite being reached first by the British.

Bikinians had education in high regard, and children were taught both Marshallese and English.

In the name of God

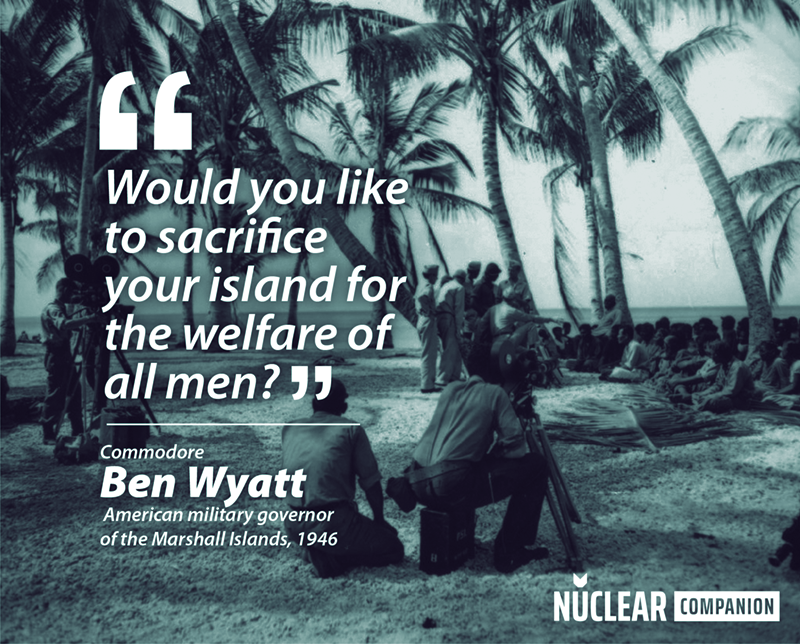

Shortly after Blandy confirmed Bikini to be the place for the tests, on Feb. 10 its inhabitants were formally requested to leave their homes.

Making the request was the job of Commodore Ben Wyatt, the deputy military governor of the Marshalls. Along with him came a set of photographers, film crews, and journalists.

Wyatt invited locals to form a semicircle around him. Possibly drawing upon that Sunday church service has just ended, Wyatt‘s speech didn’t lack a religious tone. Religion was certainly what they had most in common. Wyatt quoted the bible, a book locals were fond of, and the Jewish exodus as parallelism of their current situation.

Wyatt would later refer to the speech as a “tough job”, as he wanted to avoid the scenario in which even only one of them would be against moving.

Wyatt explained to them not about what the tests would be about. Instead, he gave a meta image of atomic energy and its possibilities to help humanity. He told locals that they were to play a role in this development by leaving their houses and moving to another island.

After discussing the proposal, the twelve leaders came to the conclusion that if it was for a greater good they couldn’t reject moving. Wyatt‘s speech was successful.

Bikinians had not moved yet and ships, aircraft, and personnel for the operation began traveling to the islands. Along with them came the media, wanting to capture the process. Wyatt even had to repeat his speech for the camera.

Natives, for their part, were also part of their show. They decorated the islands’ community center and made a ceremony to honor their ancestors which they had to repeat for the cameras as well.

Likewise, natives held the church service three times for better images. All these media requirements delayed the natives’ departure a whole day.

The journey to Rongerik Atoll

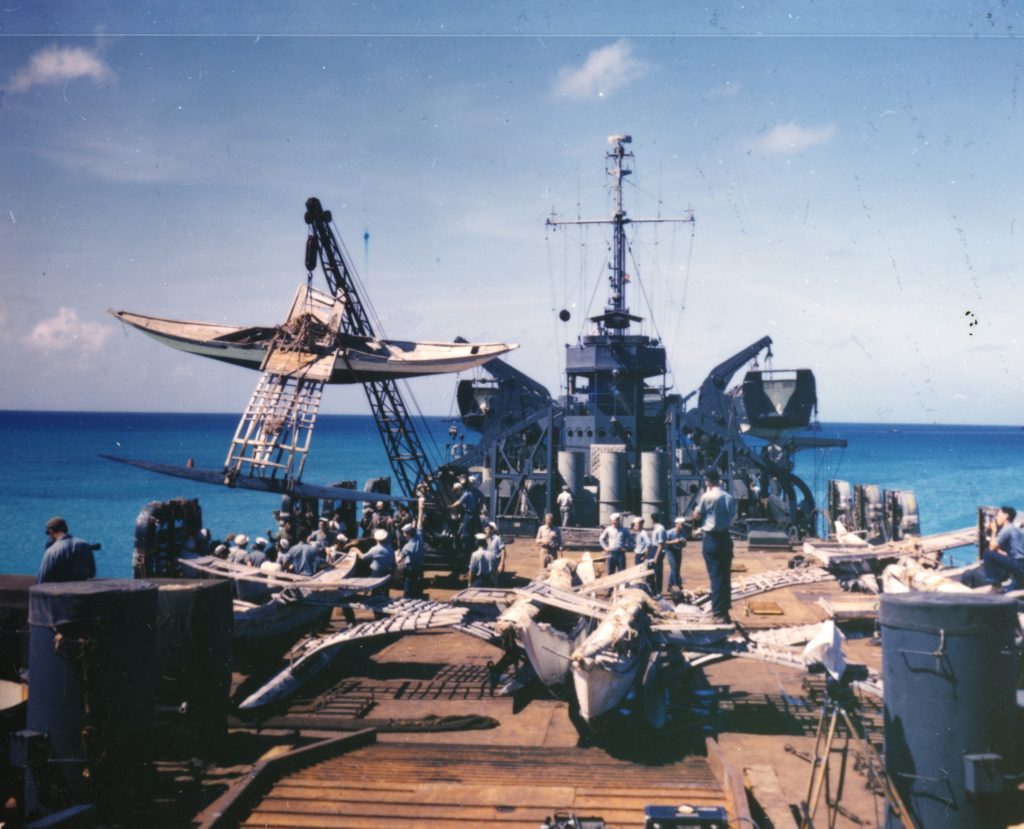

But where did they go? Chiefs decided by vote to move their people and belongings to at the time inhabited Rongerik atoll. With the help of the tank landing ship USS LST-1108, they also carried with them their outrigger canoes and houses.

There was the promise of returning but without a specific date for doing so. Bikinians moved as fast as the next month, Mar. 7, in order for the tests to have placed on the planned time.

The US government took care of constructing the public and private buildings for the new island. Wyatt’s chief of staff, Harold Grieve, also a civilian architect, designed the new village.

According to Grieve, these new islands were above Bikini‘s in terms of food natural sources. Plus, natives received two months’ worth of food and water supplies; enough time for Bikinians to develop their own stocks.

But Grieve’s prevision could not be further from the truth. Despite having chosen Rongerik as their new temporary home, among Marshallese existed the legend of this atoll as the home of demonic spirits. And while we cannot assure a supernatural power had any real influence, natives live there ended up being far from decent.

To begin with, Rongerik’s 17 islands felt short when compared to Bikini’s 36: a total of just 0.63 square miles against 2.3. Less soil meant fewer resources. And while agriculture was not viable, fish were naturally poisonous.

The press, on the other hand, kept the image on the matter of a new paradise destiny for them. From their perspective, they were in the first place pleased with contributing to end worlds’ wars, and that was that for them.

US Officials promised their deportation would be temporary and they soon started asking to return home. Unfortunately, most of them would not see their home again.

We will detail the bikinians‘s exile and hardships later in this article.

The Bomb

Now it’s time to focus on the bomb.

The bombs dropped during Crossroads were not expressly designed for the test.

They were two of the nine implosion-type nuclear bombs the US had in stock in 1946. At Los Alamos, the MK III and MK IV stood out as the favored bombs for featuring in the operation.

The 21-kt yield bomb used at Nagasaki was an MK III, as well as Trinity Site‘s. Meanwhile, as its name suggests, MK IV was the successor of the MK III.

At the time, the MK IV had yet to be tested. Thereby, using it at Crossroads was necessary for this weapon development. Lab experts, nonetheless, were more inclined to use the MK III bombs.

They had a number of reasons for backing up their decision. Firstly, the MK III bomb had not been tested enough times. Testing it again would provide great feedback for comparing its different recorded explosions. Coming up with an expectable range of power and new data from various scenarios was extremely valuable.

Another point for choosing the MK III was that the test was not about testing a type of nuclear bomb but nuclear weapons themselves. Then, a more reliable device would be more apt for such a task.

Lastly, common sense granted that a newer and untried bomb wasn’t the best option. In case of not working properly, anything going wrong would detonate negative views on public opinion.

Crossroads was the first public exhibition of nuclear weapons. In this sense, it was perceived as possibly the greatest military test in terms of catching the civil interest.

Gilda & Helen of Bikini

Scientists and engineers christianized the ABLE shot’s bomb as “Gilda”. This was Rita Hayworth’s latest movie and according to the Scientists it “kept us awake nights”. Three painters painted the words “Gilda” and a reproduction of a photo of Hayworth wearing a low-necked black evening gown. When asked about it, Rita Hayworth felt so honored that she said: “that I still haven’t come down to earth”.

Baker’s Bomb bore the nickname of Helen of Bikini, in a subtle allusion to the Trojan war and to that explosive mixture of seduction and destruction that patriarchy attributes to women as a great privilege.

As such, MK III Fat Man finally made it to the test. MK IV had to wait for its turn. At least that was the message.

MK IV‘s development had worse problems than not taking part in Crossroads, nonetheless. The team in charge of developing the MK IV was known as Z Division, divided between Los Alamos and Albuquerque. But with Crossroads, its most prominent members from both locations were transferred to the nuclear tests’ teams.

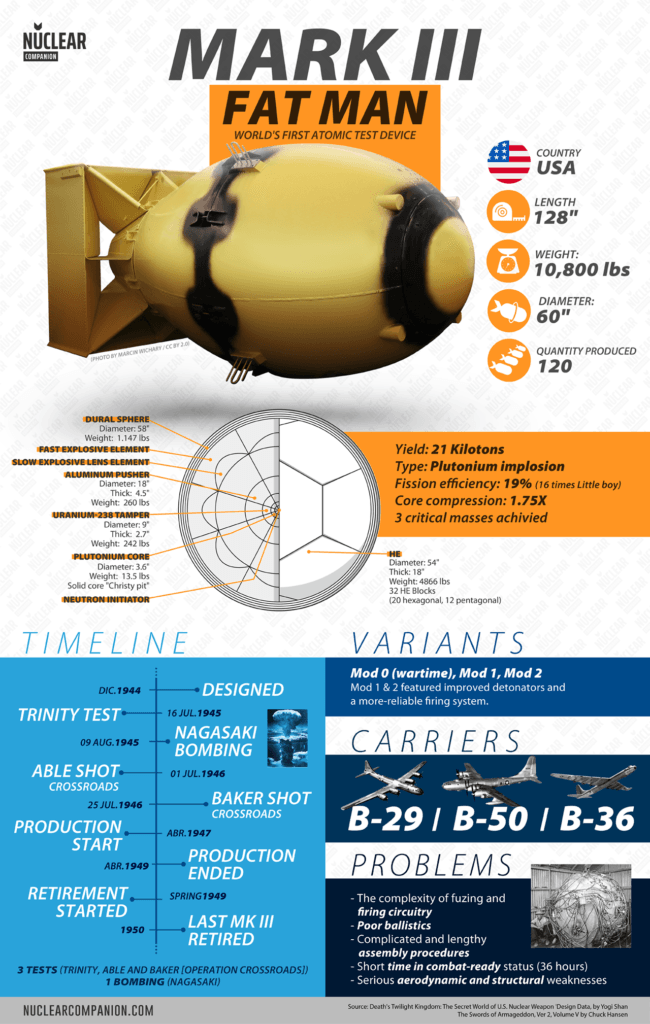

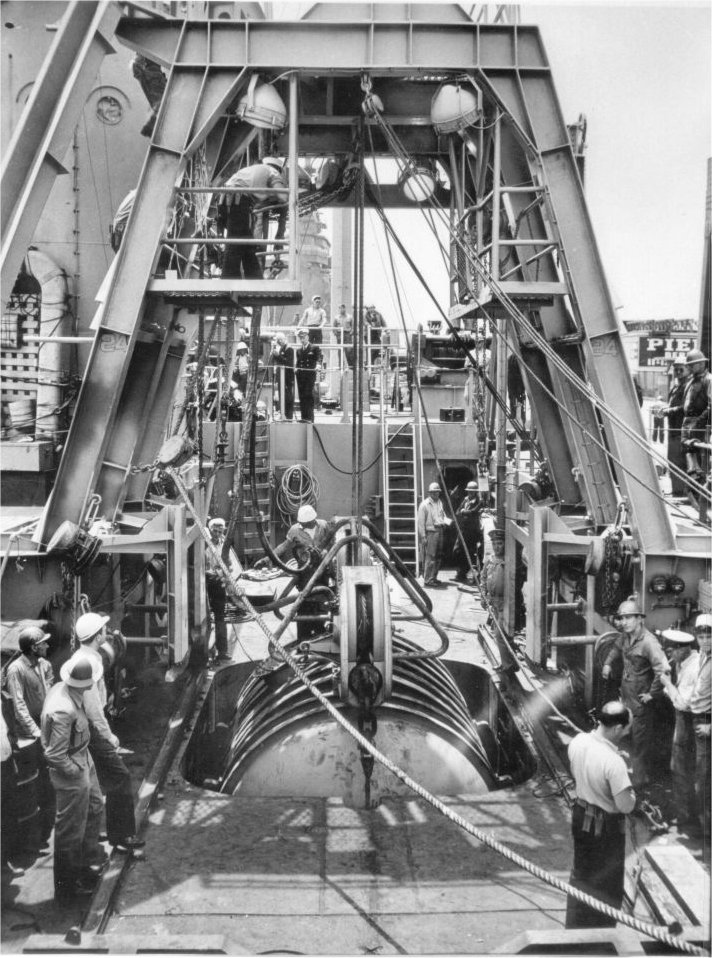

The Fatman Mark III

The bombs at Crossroads were two MK III Fat Man.

These were 12 ft long, 60 inches diameter bombs. Of their weight of around 10,800 lb, only 6.2 kg was plutonium. Through ignition, this plutonium rapidly compressed and imploded reaching supercritical mass.

Now, despite making it to the test, the design of the MK III had its flaws. It didn’t fly well, being aerodynamically unstable at reaching its terminal velocity (.9 to .95 Mach). In this case, the bomb wavered, losing landing precision.

The improvised solution, as it was the case for the one used in the warn was a set of drag plates added to its tail box. These in most cases succeeded in slowing down the weapon to a controllable speed.

At the same time, these bombs were handmade, taking a full crew of 39 engineers two days for assembling each one. After that, the bomb had to be used within 48 hours, or else the batteries of the bomb’s fuses had to be changed.

Los Alamos participation

Los Alamos National Laboratory received notice of its participation in Crossroads in Dec. 1945. The institution was expected to provide nuclear devices and technical support for the test.

Given the role Los Alamos played in nuclear weapons development, it was without a doubt the most competent office for the job. By calculating the possible outcomes of the Operation’s explosions, the Laboratory was to aid the U.S. Navy in preparing the test. Likewise, its technicians were trusted with preparing and assembling the bombs.

By Jan. 1946, Los Alamos and the U.S. Navy finished outlining the operation details. During their meetings, Los Alamos chose Dr. Ralph A. Sawyer for the position of Technical Director of Crossroads.

Alongside Sawyer, another two important names from the laboratory went to Bikini: Dr. Marshall Holloway and Mr. Roger Warner.

Holloway, from the B-Division, was head of Los Alamos experimental groups. The U.S. Navy conditioned craft USS Cumberland Sound (AV-17) as his team’s laboratory.

The experimental group, under Dr. Marshall Holloway (B-Division), had the following responsibilities:

- overall recommendations;

- to prepare an account of expected phenomena;

- to estimate the equivalent high explosive yield.

- provide instrumentation and make measurements of bomb performance.

Warner, for his part, part of Z-Division, was in charge of the weapons preparations groups. His ship was USS Albemarle (AV-5), modified for bomb assembly groups to work properly.

On the other hand, the weapon assembly group under Mr. Roger Warner (Z-Division) was in charge of:

- to prepare the firing circuits for the underwater test as well as timing system;

- to prepare and provide the atomic devices.

Los Alamos also provided medicals teams to Crossroads under the supervision of James F. Nolan and Louis H. Hempelmann. Both doctors’ teams were to examine the effects of radiation on test animals.

During the course of the operation, a C-54 connected Los Alamos’ headquarters in Santa Fe with Washington, D. C. In this way, techs at both offices were able to maintain proper communication.

In terms of nuclear weapons, Los Alamos offered a few models the Joint Taskforce could choose from. As we saw earlier, for practical reasons nuclear experts agreed on using the same type of bomb dropped at Nagasaki.

Participation in Crossroads cost Los Alamos one million dollars from its own budget. Still, its greatest sacrifice was human resources. One-eighth of Los Alamos staff, 150 technicians, dedicated entirely to the operation.

In this way, until Crossroads was over the laboratory remained short of employees for its other projects. Z division, key in nuclear weapons design, lost many of its most competent members to Crossroads, delaying the development of bomb Mark 4.

This was also the case of nuclear weapons composite cores. Such technology would only be tested in 1948 during Operation Sandstone, alongside levitated pits. Ironically, Sandstone would also require the help of the Z division, halting Mark 4’s development once again.

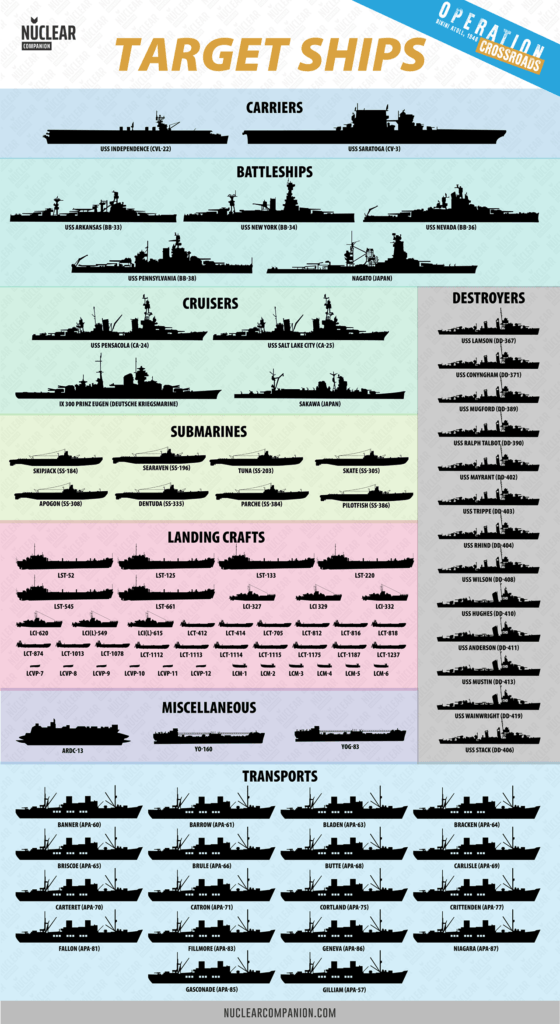

Target Ships

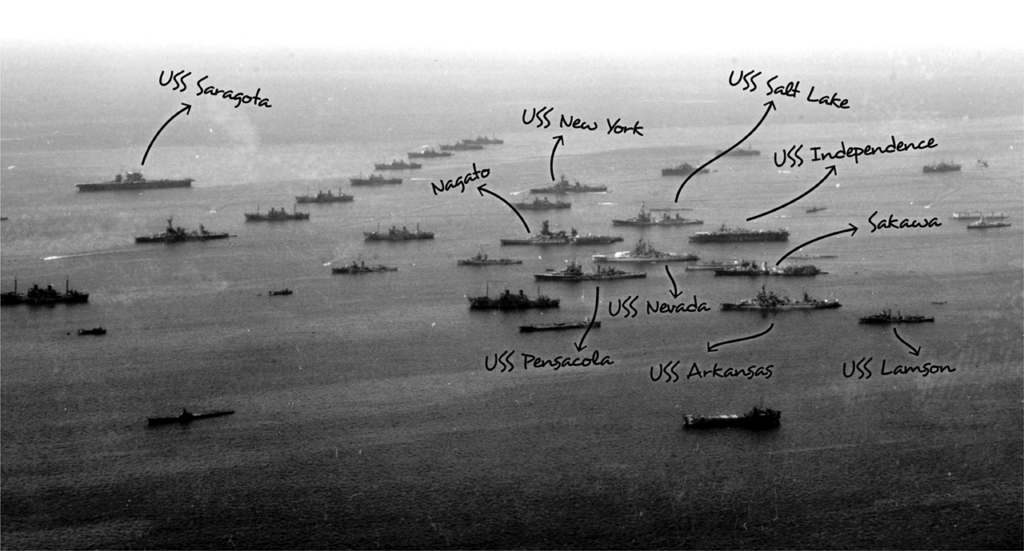

One of the most interesting points of the test was the target ships’ selection itself.

We can imagine that such selection was not, by any means, left to chance. It was, indeed, related to the objective of the experiment.

In knowing how would U.S. Navy assets stand against nuclear attacks, targets were not simply expendable and old ships. Rather, the US military chose the vessels that represented most of what the U.S. Navy had to offer.

At the same time, with the end of the war came the time for the US army to decommission several war assets. In this case, warships. As a consequence, many of the very ships that served as targets had a military history and renown of their own.

In total, almost a hundred US vessels were part of the test. The test ship’s final list, featuring three last-minute submarines, appeared on Jan. 24th:

- 2 aircraft carriers

- 4 battleships

- 2 heavy cruisers

- 16 destroyers

- 8 submarines

- 15 transport ships

Apart from testing their naval war top potential, the US wanted to expose to the nuclear explosion to a wide range of vessel types as well. In this sense, adding to the main selected crafts were a total of 47 different boats of all sorts, including landing and patrol ships.

Battleships

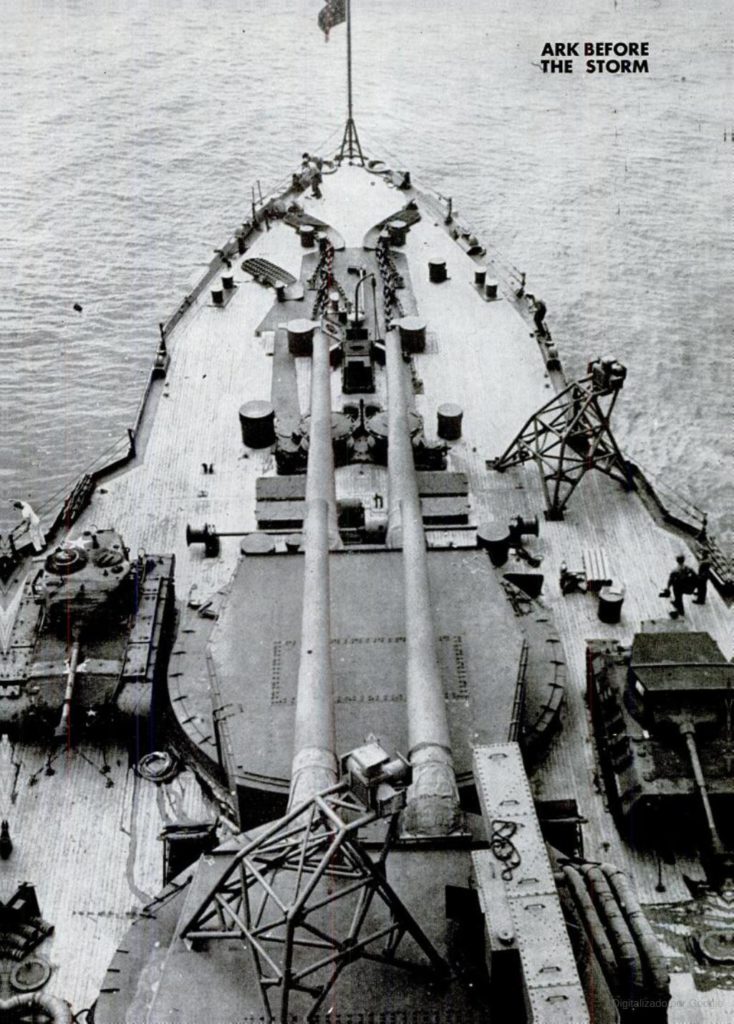

Among these ships, the most iconic ones were the four battleships.

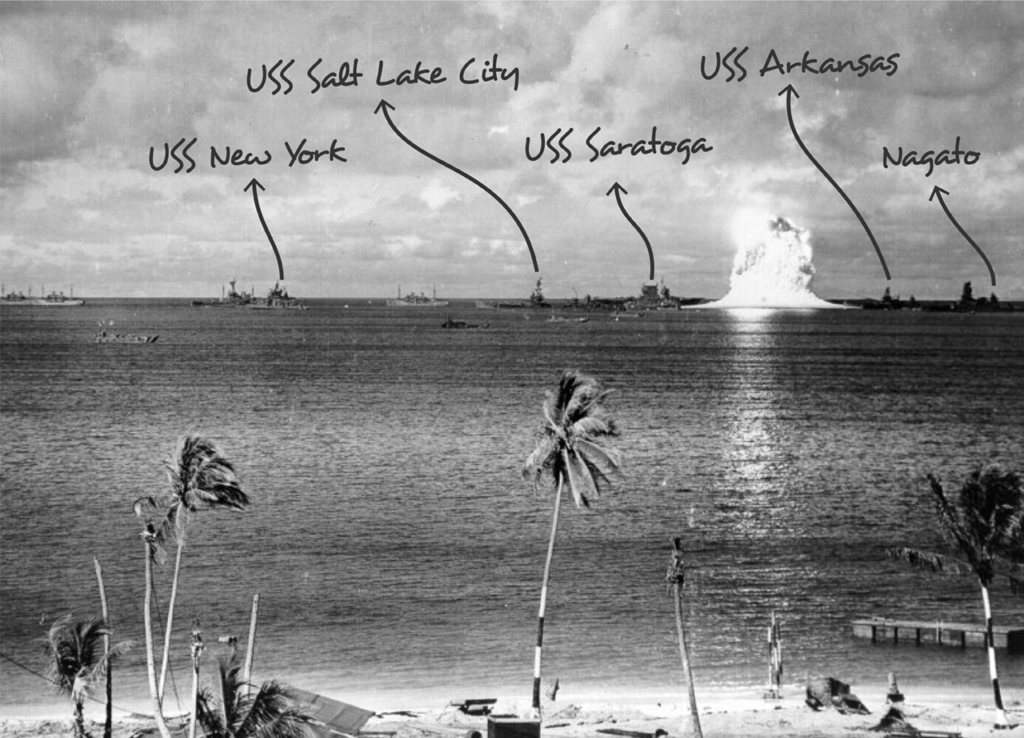

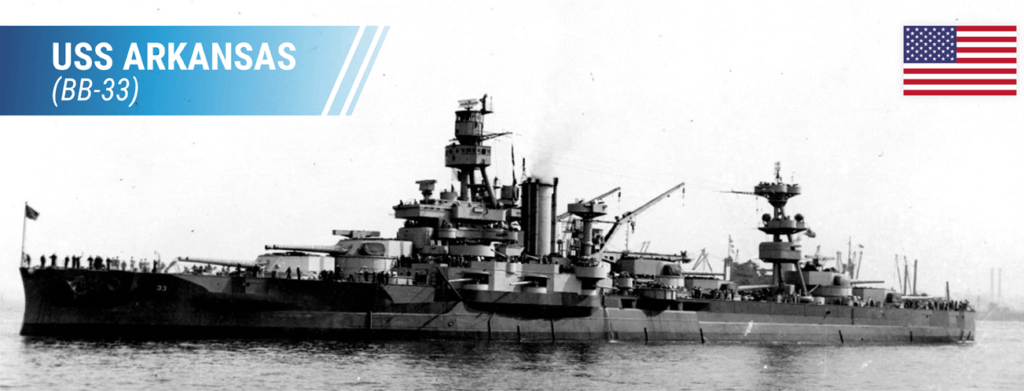

26,100-tons USS Arkansas (BB-33) or “Arky” was by then U.S. Navy’s oldest ship. As such, it had seen action in the two world wars, participating in allied campaigns on Africa and north and south of France.

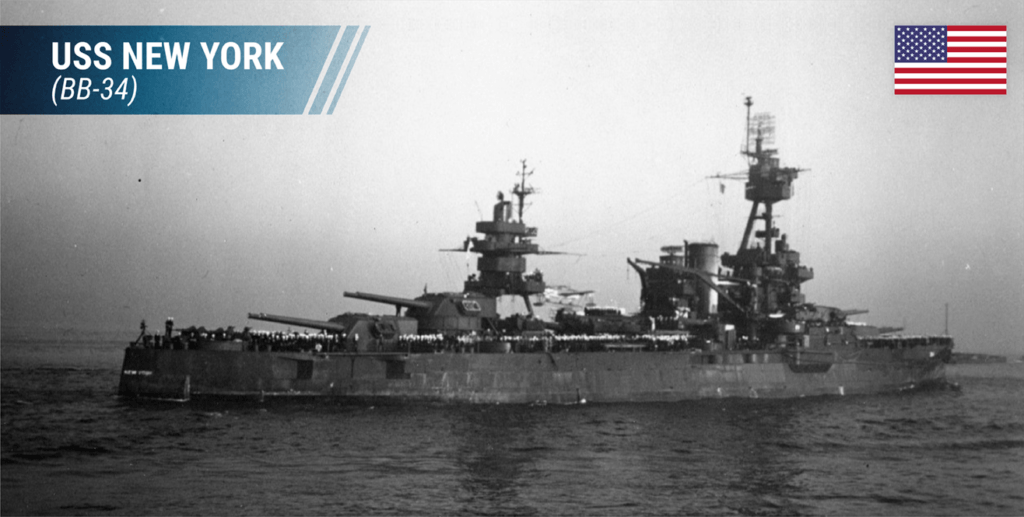

Similarly, USS New York (BB-34) had a long history of naval conflicts, participating in both world wars as well. This 27,000-ton battleship fought its toughest battle on Okinawa, where it kept shooting during 76 of the 82 days the attack lasted. Despite its constant presence on the battlefield, New York survived the war suffering no severe damage.

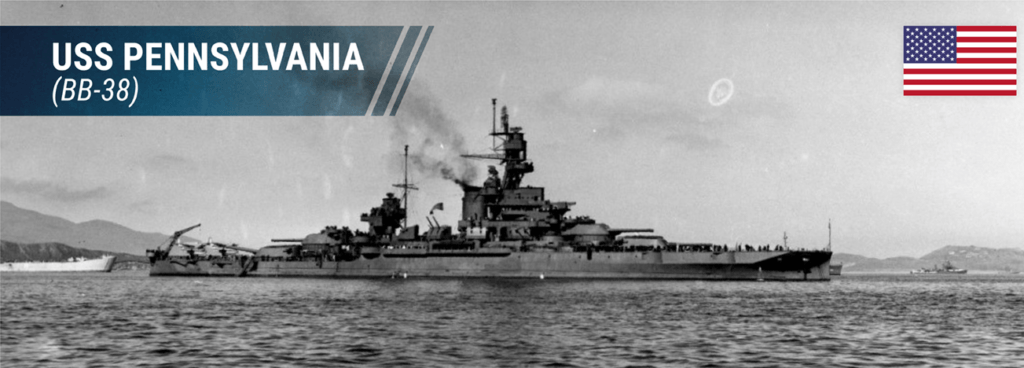

There were also two ships that were taken down on Pearl Harbor. They were 31,000-tons USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), part of 13 amphibious landings, and 29,000-tons USS Nevada (BB-36).

Nevada was possibly the most transcendent of these battleships. 30 years old at the time of the test, it was the first US oil-burning dreadnaught. It was also the first one to feature a three-gun turret.

Having survived Pearl Harbor, Nevada saw action on Normandy and later on in the Pacific. In Pearl Harbor, it was the sole battleship able to maneuver, which allowed it to survive the intense Japanese attack.

Honoring its fame, Nevada was the bullseye of the first test bombing. As such, it was painted in a bright reddish-orange combination.

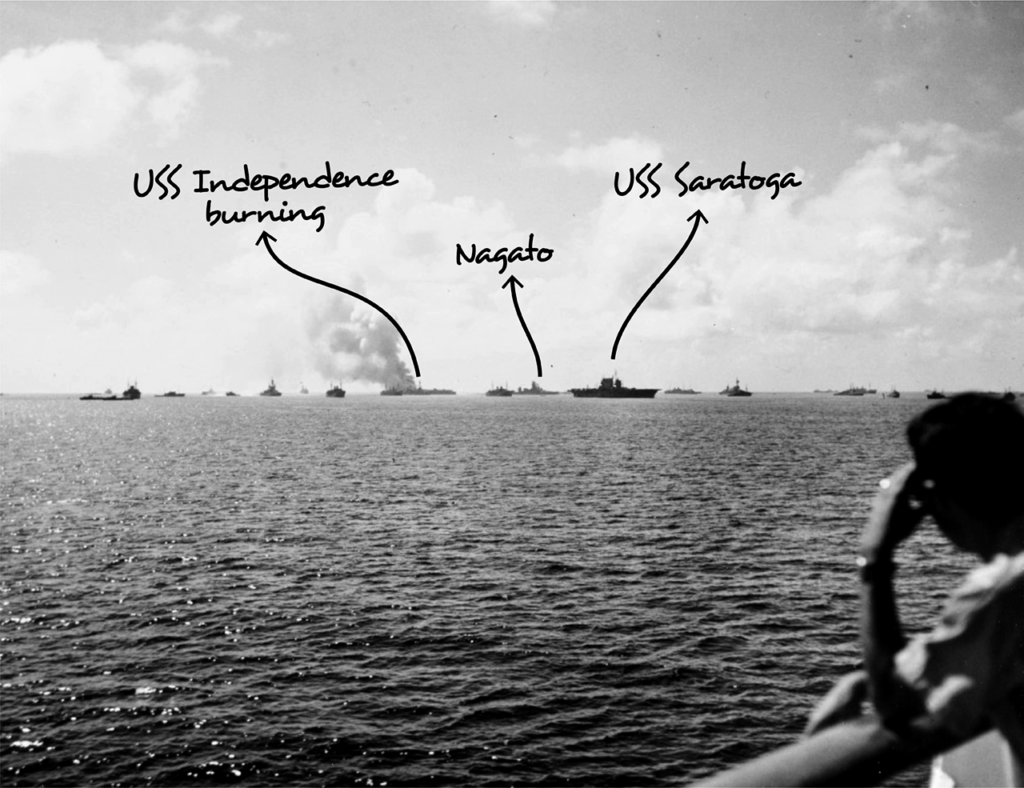

Carriers

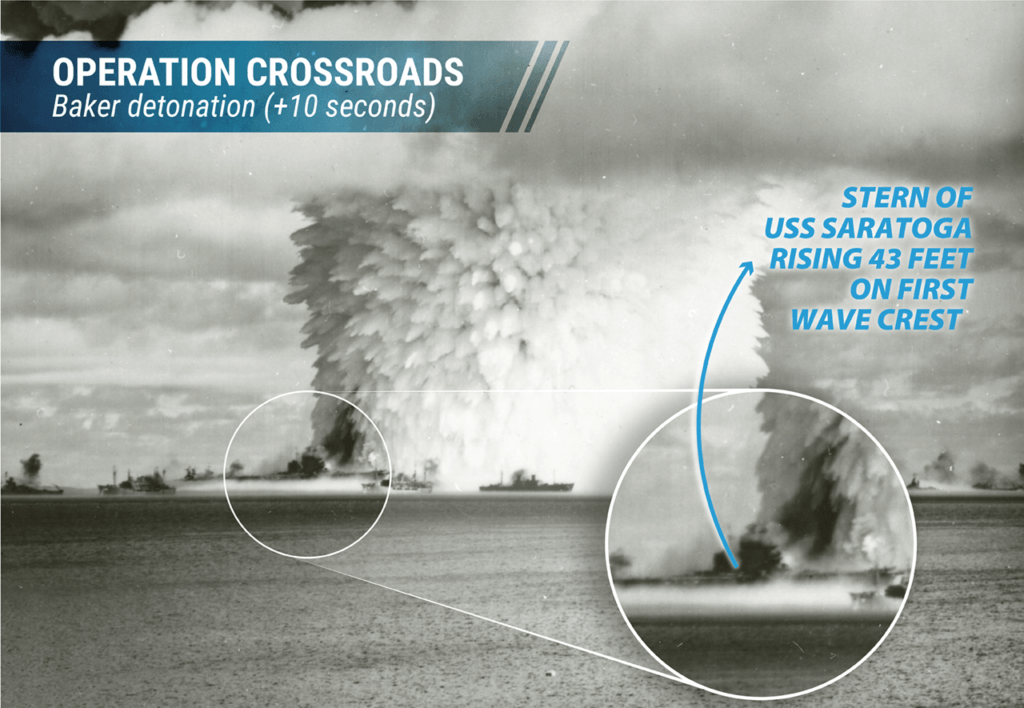

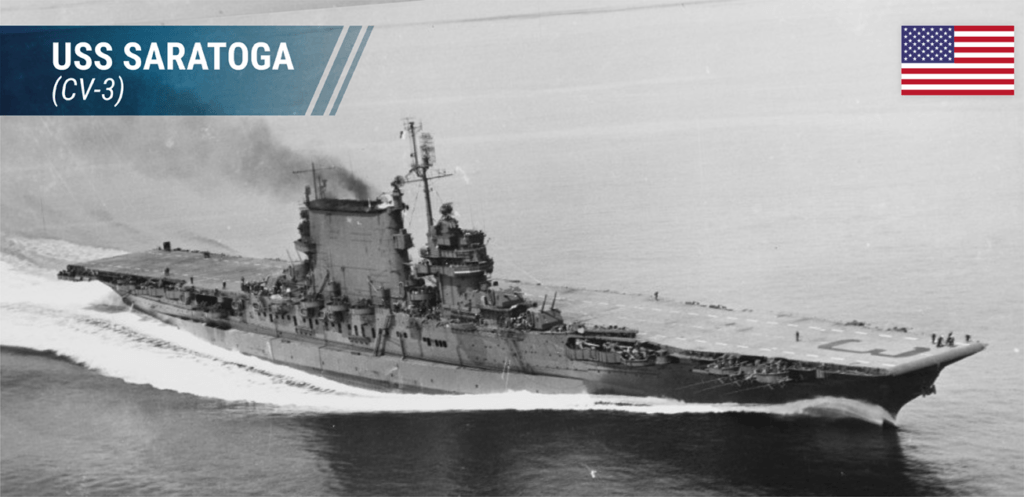

Regarding carriers, 33,000-tons USS Saratoga (CV-3) or “Sara” had made a name of its own by having been allegedly sunk a total of seven times by the Japanese. In its numerous fights in the Pacific, it endured a fire in Okinawa like no other surviving ship. After participating in attacks on Tokyo and Iwo Jima, a kamikaze attack in Feb. 1945. made Saratoga finally unfit for battle.

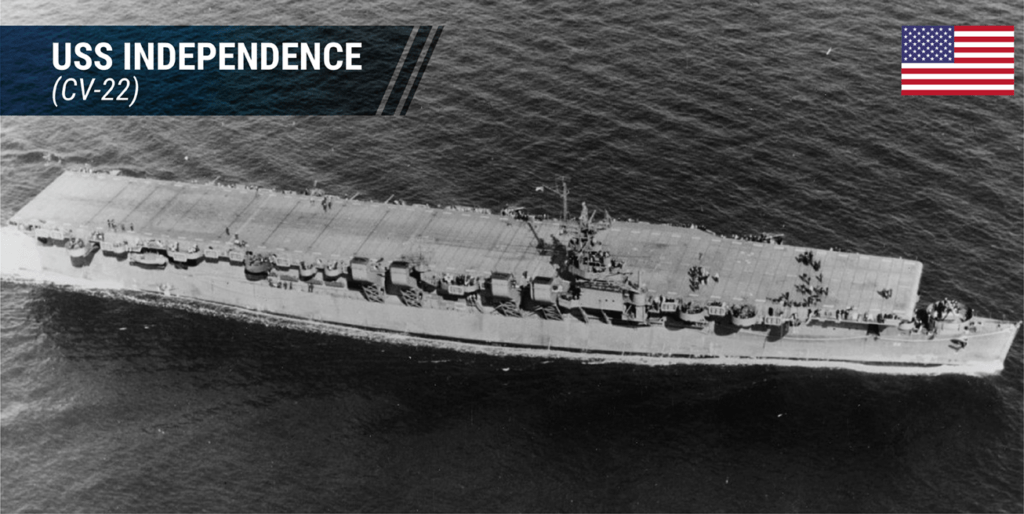

On the other hand, the other carrier, USS Independence (CVL-22), was among the youngest ships included in the test. Finished in 1943, this 11,000-tons ship acted as a fighter carrier in night missions.

Like Saratoga, Independence was used at the end of the war to bring US soldiers back home in the so-called Operation Magic Carpet.

Cruisers

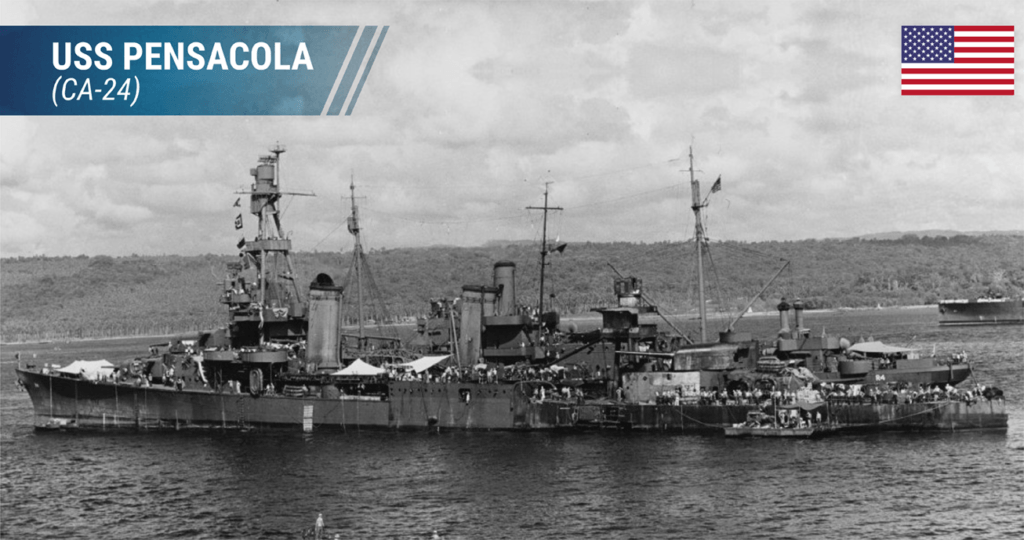

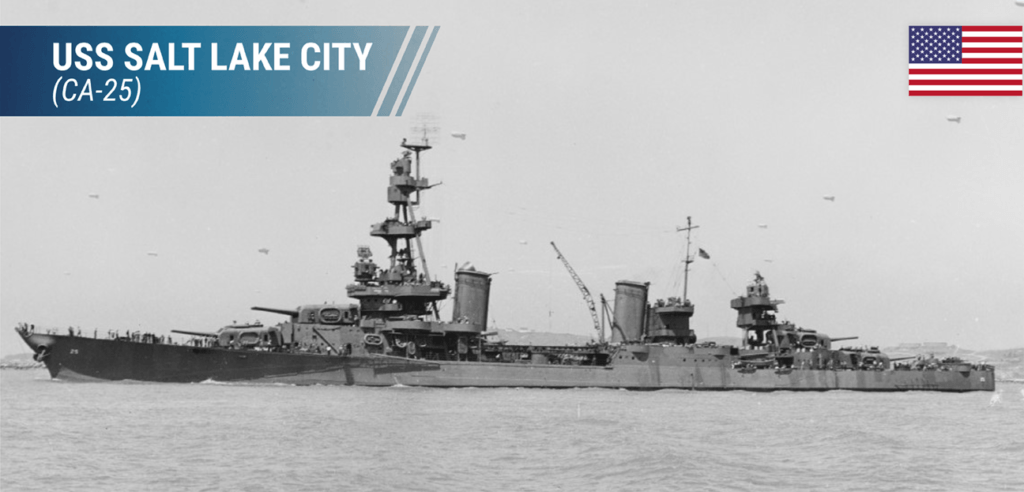

The target heavy cruisers were USS Pensacola (CA-24) and USS Salt Lake City (CA-25). They were the oldest in the U.S. Navy, and both of them had seen action in the Pacific at that time.

Remarkably, Salt Lake participated, during its 17 battles in the Pacific, in the sink of fifteen ships and the damaging of another ten. For this reason, it became known as the “one-ship fleet”, plus after helping USS Boise to escape from Cape Esperance in Oct. 1942.

Destroyers

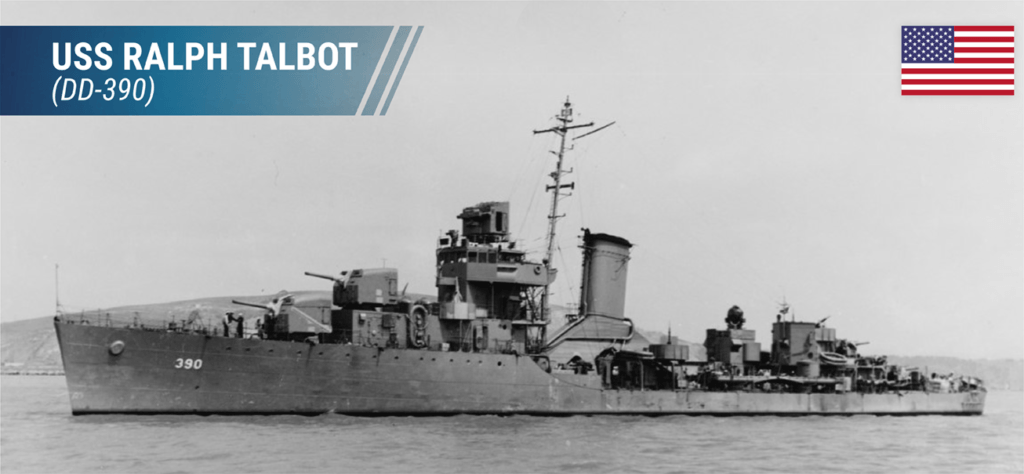

Target destroyers’ were similar inbuilt, as their weight ranged from 1,450 to 1,570 tons.

USS Ralph Talbot (DD-390) had on its achievements fourteen stars for its war service. USS Bagley (DD-386), for its part, won eight engagement stars; in earning those, it took down 11 enemy aircraft. It also participated in the rescue of almost five hundred survivors of the Battle of Savo Island.

USS Helm (DD-388) only absented two months from World War II, while USS Stack (DD-406) was part of many campaigns in the Pacific and a survivor of several attacks. Similarly, USS Hughes (DD-410) took part in nothing less than 25 operations such as occupations and raids.

USS Flusser (DD-368) was part of the ships that attempted to intercept Pearl Harbor’s attackers. Likewise, USS Mugford (DD-389) participated in taking down three attacking planes during that same battle.

Aside from its fighting capabilities, USS Trippe (DD-403) stood up acting as an escort for President Roosevelt’s conference trips.

The rest of them, USS Wainwright (DD-419), USS Mayrant (DD-402), USS Lamson (DD-367), USS Anderson (DD-411), USS Conyngham (DD-371) and USS Mustin (DD-413), held great fighting records as well.

Submarines

Last but not least: the submarines. As the destroyers, the submarines for the test were of similar built, going from 1,450 to 1,525 tons.

USS Parche (SS-384) was responsible for producing several losses to the Japanese. In six patrols, it caused 108,220 tons of damage to Japanese shipping.

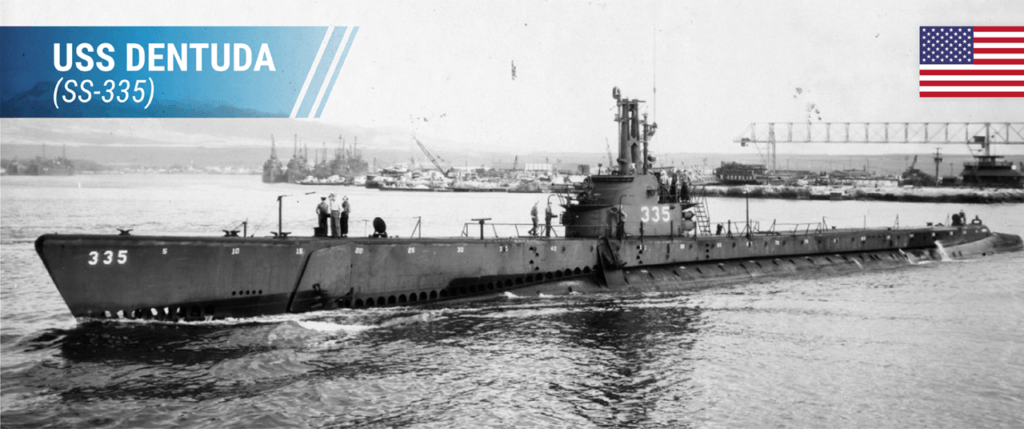

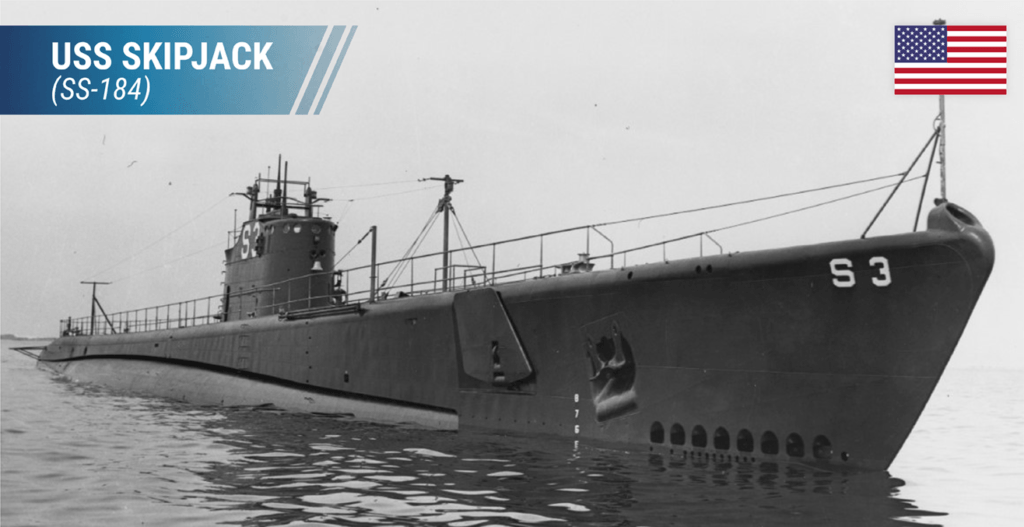

USS Dentuda (SS-335), for its part, was actually one of the newest submarines at the time. USS Skipjack (SS-184) had on its record having sunk four enemy ships, and USS Searaven (SS-196) participated in the rescue of 32 Australian soldiers.

Adding to them were the submarines USS Tuna (SS-203), USS Skate (SS-305), USS Pilotfish (SS-386), and USS Apogon (SS-308).

Foreign ships

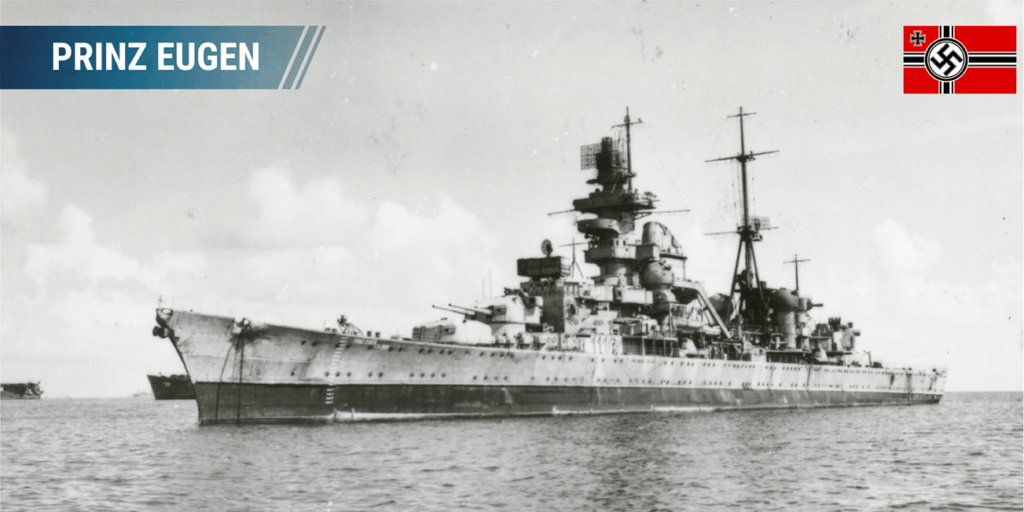

There were also the not so well-known but very interesting foreign warships, the Japanese Nagato and Sakawa and the German Prinz Eugen.

Prinz Eugen was a 10,000-tons heavy cruiser captured by a British force prior to been turned it to America. It was the largest surviving German vessel to making it out of the War.

She was named after Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663–1736), an Austrian field marshal who fought France and the Ottoman Empire. This ship made headlines in the early years of the war:

- First, in May 1941 by assisting the German battleship Bismarck sinking the HMS Hood. The Hood was the oldest and best-known capital ship in the entire Royal Navy.

- And then, together with battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, she participated in the dash through the English Channel (Operation Cerberus) in February 1942.

Prinz Eugen surrendered to the British at Copenhagen, Denmark, 7 May 1945.

From the Japanese side, there was the light cruiser Sakawa. This 6,000-tons ship never actually saw battle. In this sense, it was the only World War II light cruiser that made it to the end of the war without suffering any damage.

Sakawa was commissioned at Sasebo on 30 November 1944. She replaced the sunken light cruiser Tama as the flagship of Destroyer Sentai (squadron) 11 in December 1944.

Fuel shortage preventer her from participating together with Battleship Yamato in Operation Ten-Ichi-Go (Heaven Number One). Operation Ten-ichi-go, was the most ambitious suicide mission of the war. Yamato, light cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers were sunk by US aircraft while attacking the U.S. Navy‘s invasion force at Okinawa.

The light cruiser remained in the Inland Sea on training duties until July 1945 and surrendered intact on 15 August 1945.

An then there was Nagato, the last surviving Japanese Battleship.

This 32,720-ton battleship was very special for the US. It was from Nagato that Yamamoto planned and commanded the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

She was also special for the Empire of Japan as as we will see in the next section.

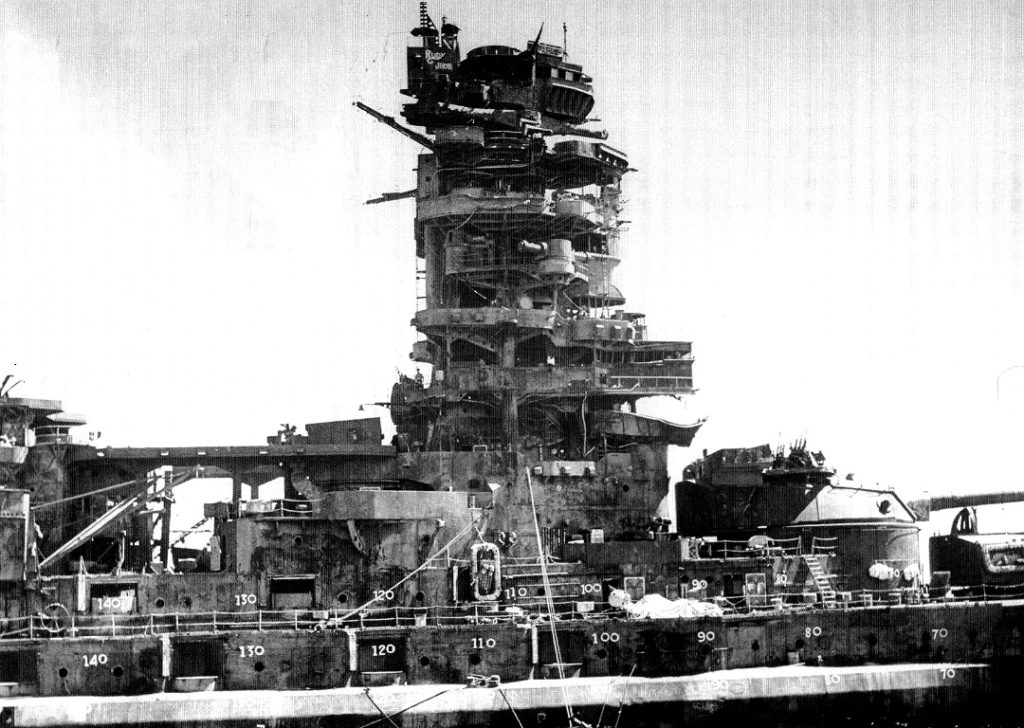

Nagato

The battleship Nagato represented a milestone in Japanese naval construction.

Hiraga Yuzuru, the most famous Japanese naval architect, designed the ship. He turned away from the British model that Japan had previously adopted for capital ships. As a result, he created a ship that for some decades was the ultimate expression of Japanese naval power and prestige.

For instance:

- She was the first battleship in the world to carry 16” guns

- At 32,000 tons she was one of the largest battleships in the world

- She was the largest yet built for the Imperial Japanese Navy.

- She was able to counter the American Colorado and British Queen Elizabeth classes.

Nagato namesake

The Imperial Japanese Navy christened its Battleships after ancient provinces(Yamato, Fuso, Yamashiro). On the other hand, Battlecruisers were given mountain names (Haruna, Kongo, Kirishima). In this case, Nagato was the name of a province in pre-Meiji Japan. It was home to one of Japan’s most powerful warrior clans.

On commissioning, Nagato instantly assumed the role of the fleet flagship. She began the peacetime career of most of the world’s capital ships: exercises, training, protocol, and foreign visits.

During the 1920s and ’30s, Nagato together with this sister Mutsu were the national pride of Japan. That changed only with the commissioning of the battleship Yamato in December 1941.

Nagato wartime service

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. On that same day, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto took formal command of the Combined Fleet onboard his new flagship: Nagato. Then, Yamamoto on his cabin in Nagato, utilizing maps and intelligence summaries, prepared the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Finally, on December 2 1941 Nagato sent one of the most famous messages in naval history:

NIITAKA YAMA NOBORE 1208 (“Climb Mount Niitaka 1208”)

In other words, proceed with hostilities against the USA, Great Britain, and the Netherlands on 8 December. So, signaling the attack on Pearl Harbor.

During the war, she participated in the battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf. In the latter, Nagato took several bomb hits. As a result, she was drydocked in Yokosuka, but materials and fuel were scarce. The old ship finished the war as a floating anti-aircraft platform in Yokosuka.

On August 30, 1945, she was boarded by U.S. Navy personnel.

Nagato’s journey to Bikini

This list of events taken from Steve Wiper’s Warship Pictorial No. 38 – IJN Nagato Class Battleships:

29 August 1945: USS Missouri (BB-63), Iowa (BB61), numerous minesweepers, destroyers entered Tokyo Bay, anchor at Yokosuka.

30 August 1945: U.S. Navy boarded NAGATO anchored in Yokosuka, capture Nagato, symbolized unconditional surrender of IJN.

2 September 1945: Official surrender of Japan held aboard MISSOURI.

15 September 1945: Removed from U.S. Navy List.

1-14 March 1946: Nagato made three test runs in Tokyo Bay.

18 March 1946: Nagato departed Yokosuka for Eniwetok with a U.S. Navy crew of 180 men, with light cruiser Sakawa . Only 2x of Nagato’s 4x screws operation, best speed 10 knots.

26 March 1946: Nagato’s hull unseaworthy, pumps cannot keep up with leaks. Nagato shipped 150 tons of seawater in forward compartments, stern compartments counter-flooded with 260 tons water to maintain balance.

28 March 1946: Sakawa broke down. Nagato set tow-line to Sakawa, then Nagato ran out of fuel. Both ships stopped in bad weather.

30 March 1946: Two USN tugboats arrive from Eniwetok. Nagato taken in tow by USS Clamp (ARS-33). Without power, Nagato took on more water and a seven-degree list to port, towed at 1 knot.

4 April 1946: Arrived Eniwetok, flooded compartments pumped out, repairs to hull and machinery.

May 1946: Steamed at 13 knots, 200nm to Bikini Atoll.

1 July 1946: Operation Crossroads, Bikini Atoll.

Support Ships

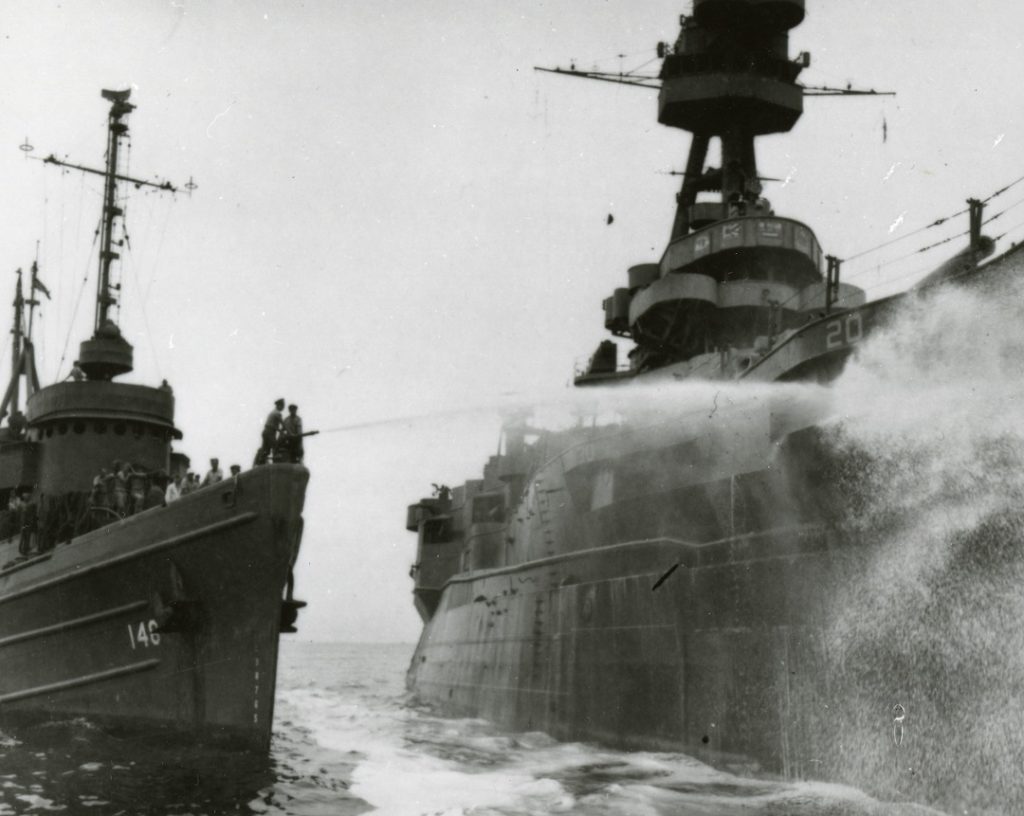

Organizing the target ships was the job of Rear Admiral Frank George Fahrion (1894-1970). This group of the operation was the Joint Task Force 1.2.

Not all the ships from this group were target ships, although most were. Nontarget ships supported the preparation, placement, and salvage of the targets. It was also among Fahrion’s duties to provide safe transport to scientific recognition of the ships after the explosion.

During the test, Fahrion was aboard USS Fall River (CA-131), the flagship of his task group, and one of the newest US heavy cruisers. It was so new that, finished in 1945, it did not even make it into World War II.

Rear Admiral Frank George Fahrion (1894-1970)

Native from Pickens, West Virginia, Fahrion graduated from the U.S. Navy Academy in 1917. After serving aboard USS South Dakota in World War I, he achieved a master’s degree in Science at MIT.

During World War II, Fahrion was in charge of different destroyers’ divisions in the Atlantic as well as in the Pacific. He was given command of the USS North Carolina in 1944. Being this ship one of the newest at the time in the U.S. Navy, his appointment to command was a sign of his leadership ability on the water.

In 1945 Fahrion participated in the Okinawa campaign commanding the Cruiser Division Four. With the end of the war, he was in charge of transporting Allied prisoners from Japanese soil. During this period, he also commanded the first American soldiers to enter Kyushu when the war ended.

When Admiral Blandy reached him for communicating his role in Operation Crossroads, he was acting as commander of a task force in Japan.

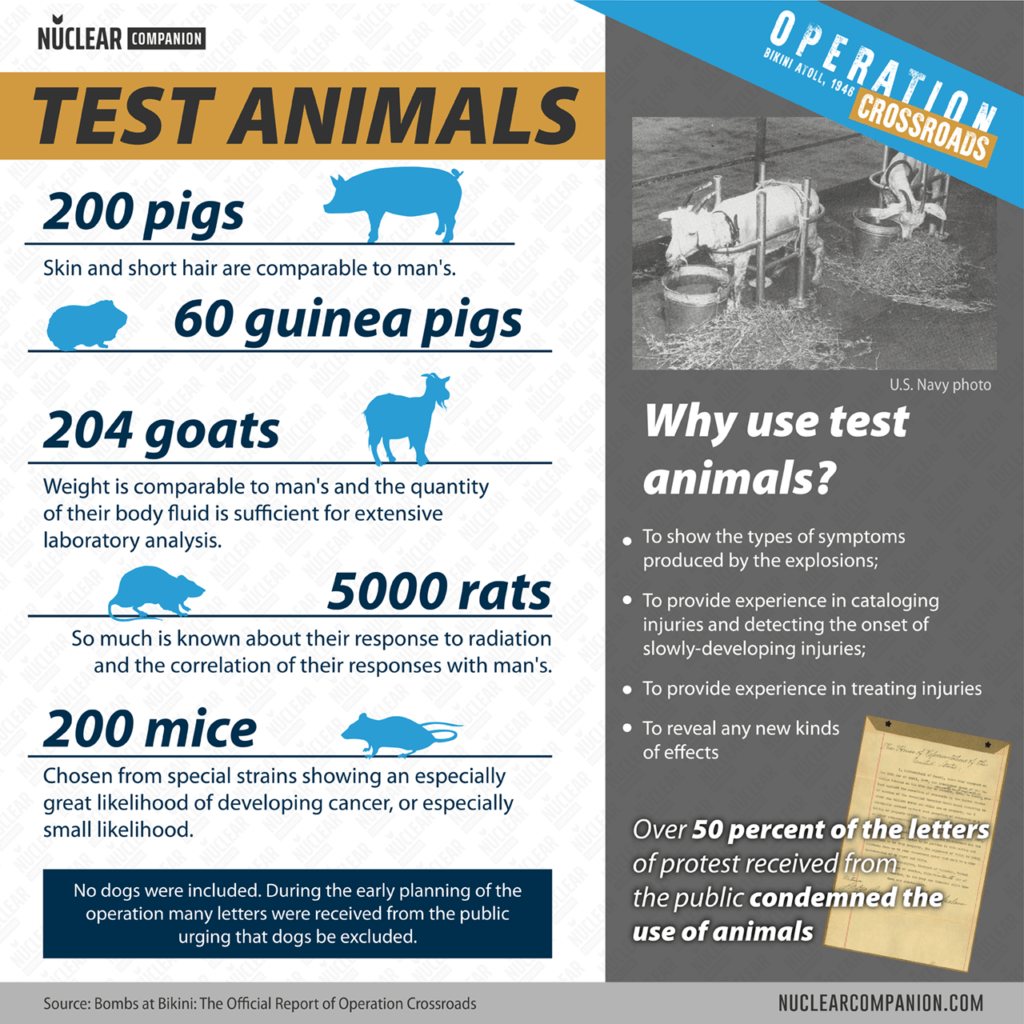

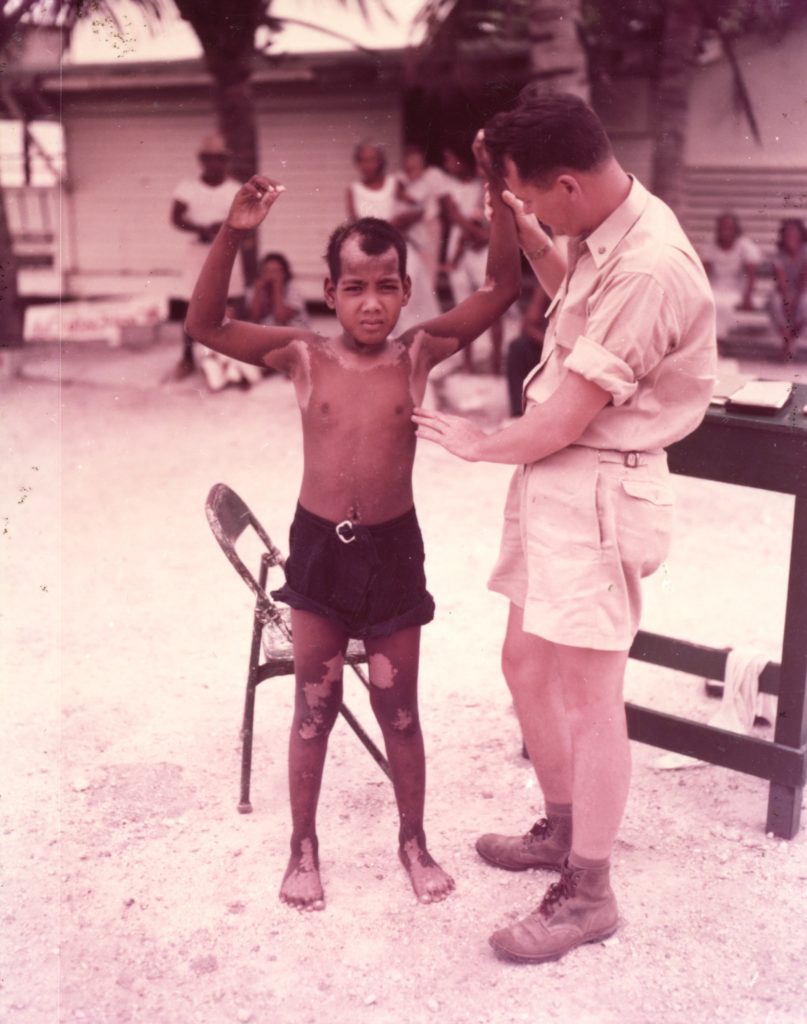

Testing in Animals

Another part of Operation Crossroads had as objective to recognize the nuclear explosion’s effect on biological beings. Most of all, the army wanted to know about the damage these new weapons could do to them in the short and long term.

It is true that the nuclear bombs detonated on Japan did show a great number of these deadly effects. Nonetheless, the US army wanted to measure them this time in a controlled environment.

The chaotic war scenario made it difficult to know if a certain wound or illness was due to the bomb itself or to a previous or posterior cause. In this way, the U.S. could study the bomb effects without the interference of other variables.

This is why the U.S. Armed Forces included live animals in the test as a key component of it after scientists insisted on it. Their inclusion was firstly denied by Blandy, yet he had to admit later that they were indeed part of it.

“The important thing to bear in mind is that this aspect of the test will save men’s lives in the next war—should there be one. Our doctors feel that they cannot draw complete deductions on what may happen to man by instruments alone; therefore, they desire the use of animals.”...“

a minimum number of animals will be used. We regret some of these animals may be sacrificed, but we are more concerned about the men and women of the next generation than we are about the animals of this one.“

Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy

Surely, the use of animals brought global attention from animal rights groups against the cruelty of the experiment. In this sense, although dogs were ready to be part of the test, public pressure in the form of letters made Blandy desist from introducing them.

Animals

The list of animals involved goes like this:

- 5,000 rats

- 204 goats

- 200 pigs

- 200 mice

- 60 guinea pigs

- Thousands of fruit flies

Pigs were chosen specially for their skin, similar to humans, allowing scientists to know how would it react to radiation. Likewise, goats made it to the test for their human-like weight and respiratory system. Of these goats, four had particular psychoneurotic behaviors that would also become part of the research.

At the same time, the scientist chose to test goats due to the particular properties of their blood. Goat’s blood has a higher density of red cells than humans, which are also considerably smaller. This would provide a distinct object for examining the effects of radiation in blood.

Operation Crossroads also included seeds and soil samples located near the explosion. These were relevant in knowing what kind of lasting effect radiation has on human basic resources such as land and farming. Even viruses, toxins, hormones, and vitamins had their place on the test.

The U.S Armed Forces ere indeed interested in taking as much valuable knowledge of the test as they could.

In this way, for this large biological research, the U.S. Navy created the Naval Medical Research Section. In it were many U.S. Navy officers and members of the Chemical Warfare Service and Biological Warfare Division of the U.S. Army. At the same time, adding to them were civilian scientists such as physicians and veterinarians.

In charge of the medical research team was R. H. Drager. His team was in charge of performing autopsies on the animals’ bodies. They were looking for two radiation-related afflictions: cancer and radiation hereditary defects.

In this sense, cancer was the reason why mice were in the test. Moreover, the operation was actually backed up by the National Cancer Institute.

The experiments also included the testing of potential medicine for radiation poisoning. Among them were penicillin, iron compounds, folic acid, and blood hemoglobin derivatives.

Physicians also wanted to experiment with medical practices like liver extractions. They also tested the hypothesis that blood injections could have saved many lives in previous nuclear explosions.

Animals began to be loaded in May 1946 from San Francisco and set off the first of Jun.

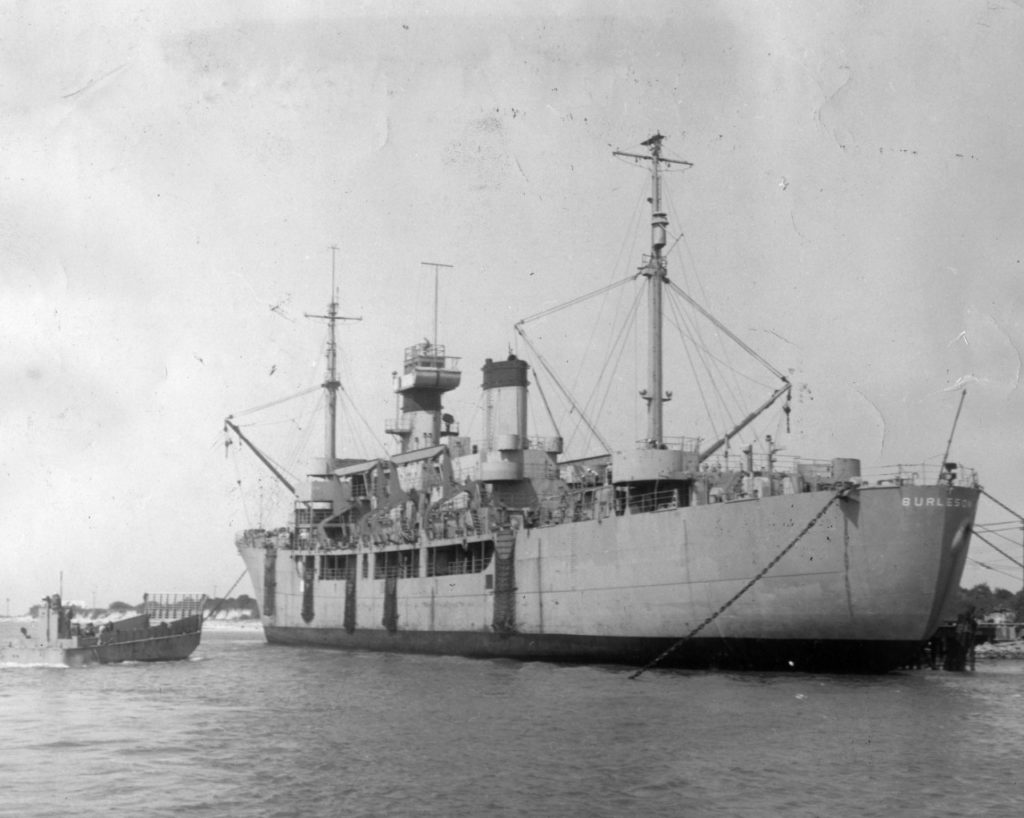

A modern Noah’s Ark

Attack transport ship USS Burleson (APA-67), named after the Texan county, arrived at Bikini with all the animals for the test. This ship had set sail for the first time in 1944 to serve in World War II. At that time, the ship could ship as many as a thousand fully equipped troops.

Yet, after the war, Burleson mutated to serve as transport for the animals of Operation Crossroads in the Joint Task Force 1. Burleson’s transformation included a visit to the Hunters Point Navy Yard (California). There, engineers added to the ship its onboard research laboratory.

At the end of the adjustments, Burleson’s specialized staff had everything they needed for dissecting the animals. In this sense, at the time it had most likely the top-notch onboard research facility in the world.

Burleson was also equipped with dedicated rooms for the animals to drink, sleep, and eat. As a matter of fact, it transported around 90 tons of animal food like hay and grain and a large enough water supply from evaporators.

Big mammals, goats, and pigs even had their own wooden pens where before were quarters for transient troops. Each of these mammals had their ears notched and tails tattooed for numbering. Rats, for their part, had their cages racked in a separate room.

Burleson’s deck, on the other hand, was specially adapted for the animals. It was covered with concrete for better footing and had drainage and disposal chutes aggregated. As a result, this ship became, in words of an army general, a “great, dirtless farm, a palatial hotel for animals”.

C. F. Stillman, captain of the ship, shared this view. Despite their fate, army care for the animals was the highest. Stillman, who declared himself to be an animal lover, put a lot of emphasis on the animals’ comfort as if they were regular passengers.

Experienced Handlers

Two divisions took care of the animals’ integrity. The crew was composed specifically of personnel from the 12th Naval District with a background in husbandry.

In this way, besides the regular crew of 190 individuals, an extra of 25 volunteered for taking care of the special passengers. Most of them had experience dealing with animals, and in the rather short time they spent with them they ended up petting them.

Main Veterinarian

The head veterinarian was Captain Dr. Robert P. Wagers. Graduated from Ohio State University in 1936, he was a former Kansas State college faculty member. Before the operation, he had spent five years in this position in the School of Veterinary Medicine.

In 1942, Wagers left the institution on military leave of absence as he had an interest in animal research. As such, he became an assistant in the chemical laboratories at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland.

The ABLE day Bombing competition

Operation Crossroads was not simply a routine test for recently created Strategic Air Command. It was, in any case, a test on its own capability. Representing the US Army aerial nuclear force, it was SAC‘s very first nuclear weapon deployment official test.

It’s not hard to grasp, then, how SAC had the highest concern in finding a bombing crew to match up. Those in charge of the dropping had to be but the very best the US Air Force could offer and had the experience to back that up.

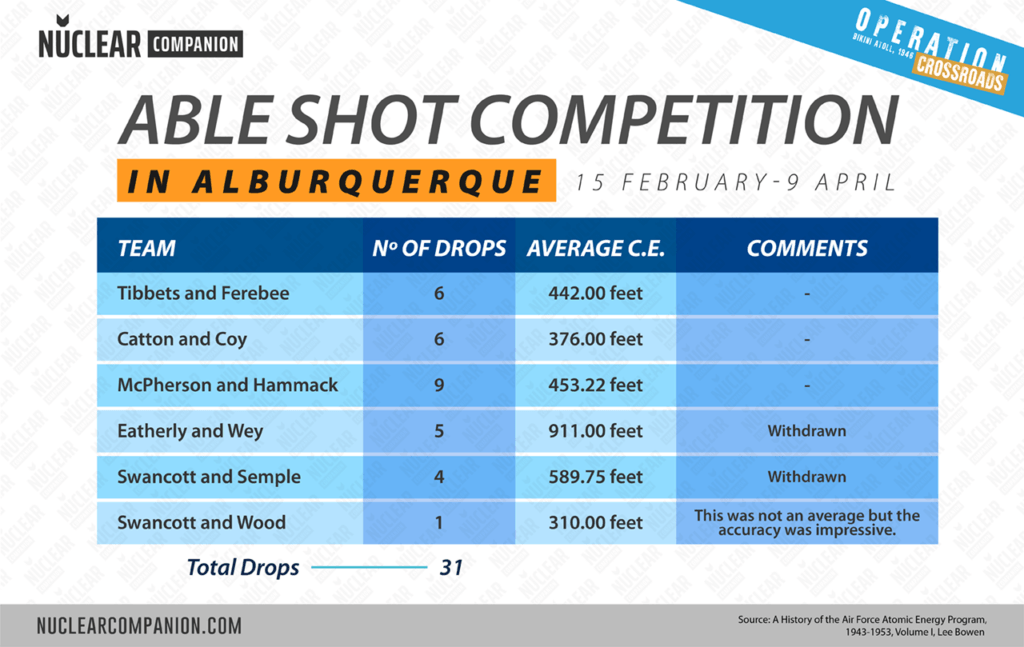

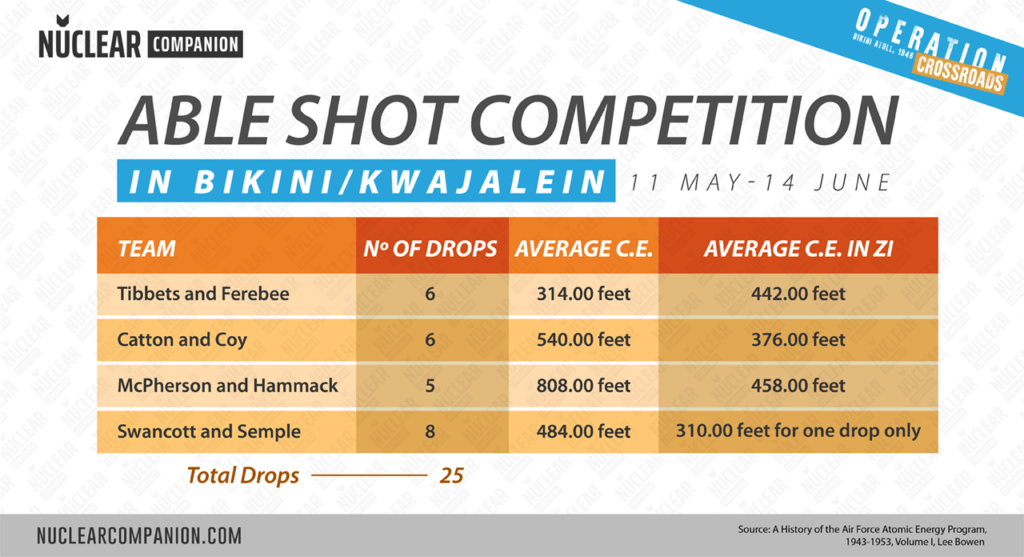

The Air Force’s headquarters decided to determine who would perform the nuclear dropping by a bombing competition. After an extensive selection process, five crews made it for determining who will make it to Operation Crossroads. SAC chose five bombardier crews for the Air Attack Unit, assigning to each one the required crew personnel for a B-29.

The Pilot/ Bombardier teams were:

- Colonel Paul W. Tibbets / Maj. Thomas W. Ferebee

- Maj. Claude R. Eatherly / Lt. Franklin Wey

- Maj. Jack J. Catton / Lt. C.L. Coy

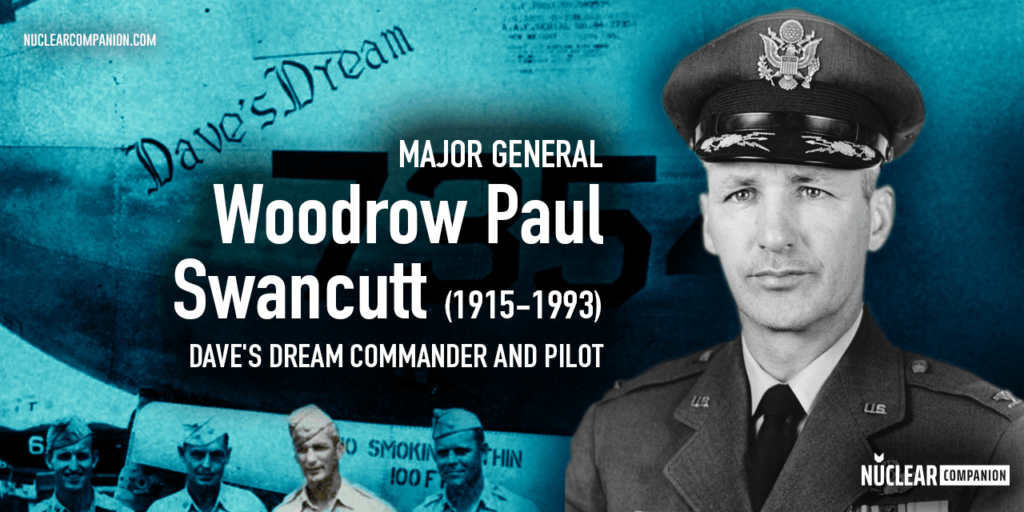

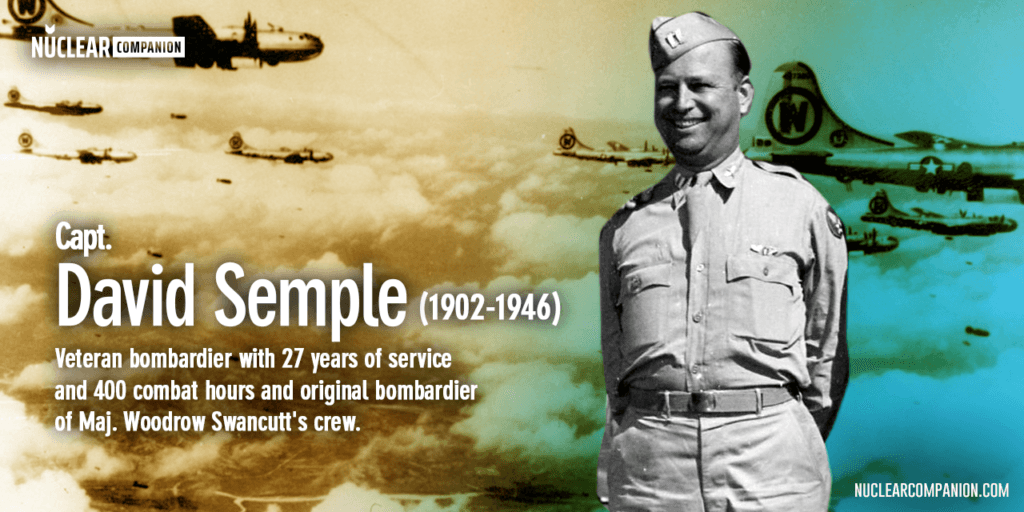

- Maj. Woodrow Swancutt / Capt. David Semple

- Maj. W.R. McPherson / Lt. C.R. Hammack

One of these crews was the same in charge of the Hiroshima dropping. Col. Paul Tibbets was in front of it, alongside Tom Ferebee (bombardier) and Ted Van Kirk (navigator).

Considering their unique experience, Tibbets and his crew were anyone’s first option for the job. But why organizing a competition in the first place, then?

We should consider that the Air Force had an interest in having more pilots trained in these sorts of weapons, that is, nuclear weapons. In this sense, the competition’s secondary objective was to make more aircrews used to the know-how of nuclear droppings.

Another relevant crew was Cap. David Semple and Woodrow P. Swancutt’s. Born in Riverside, California, Semple had meritoriously been part of the 19th Bombardment Group. Before the competition, he had earned the Legion of Merit for his 400 hours of air service.

Swancutt, for his part, had been a B-29 pilot in the 40th Bombardment Group for the 20th Bomber Command. This was the unit in which the B-29 bombardier entered World War II. Swancutt’s flight experience led him to Asian countries like China, Burma, and India, as well as to the Pacific.

In these locations, Swancutt participated in a total of 49 missions. Among them was the first b-29 daylight bombarding, which was on the Yawata Steel Mills in Japan. His unit received the Presidential Unit Citation for this particular mission.

Albuquerque

From Feb. 15 to Apr. 9, the competition’s first part took place in Albuquerque’s desert. The crews had at their disposition many practice bombs in possession of the Manhattan District. This was the same engineering district in charge of the famous Project Manhattan.

On the ground, following and analyzing droppings’ data were an SCR-584 microwave radar as well as RC-294 plotting equipment. Each inside its own van.

These eight weeks in Albuquerque resulted in a lot of bombing. The crews made a total of 40 simulated droppings of which 31 were written down as successful, proficient drops.

Albuquerque’s desert offered great visibility to recognize targets set for droppings. Plus, New Mexico had ideal steady winds at different altitudes. These winds were great not necessarily for maneuvering but for more precise bombing calculations.

Furthermore, Manhattan engineers benefited a great deal from these practice droppings. With so many test drops, they were able to learn about the firing mechanism of the bombing process.

In fact, when the competition started the Manhattan district had the only bombing tables made for this bomb. However, the data they had was no good for the crews.

Fatman’s tables, containing the dropping settings for Able test’s bomb, were only for low altitude targets. As such, they couldn’t be reliable for the test droppings been made in Albuquerque.

These tables were put together by Captain Semple himself when he was part of the Manhattan District the year before. Likewise, it was him who noticed, after the initial droppings, that these tables wouldn’t be of help. Semple then started to work on contingency tables specifically for Albuquerque’s atmospheric conditions. Soon enough, Semple’s calculations eliminated 75% percent of dropping errors.

But for getting rid of more flaws in the bombing process it was necessary to have more information on the composition of the bomb itself. In this sense, since day one the crews required all the ballistic information of the Fatman bomb.

This was, nonetheless, top-secret information in the hands of the Manhattan District. The Manhattan District was reluctant to provide such information. Ballistic tables for the Fatman bombs arrived at Kwajalein Atoll only by May 8, yet in time for the second part of the competition.

Sadly, Semple wouldn’t make it to Kwajalein. He died on Mar. 7 when he crashed in a B-29 near the small village of Las Lunas, New Mexico. He was only 45 years old.

With Semple’s death, the Task Force and Task Group 1.5 lost an important asset in the test course. At the time of the accident, he was still working on the new tables for the bomb.

Yet, the greatest loss was for Semple’s team. From Feb. 19 to the 23, they had made four different drops and were still in the run for winning the competition. But Semple’s death left them without a bombardier and on the verge of having to abandon.

This would have been the case if not for Maj. Harold E. Wood, aka “Lemon Bar”, the nickname he received from other officers for his luck with the slot machines.

As a bombardier, Wood fought in 24 missions in World War II. He was part of two Air Force leads, as well as four and five Division and Wing leads respectively.

Once a grocery clerk in Bordentown, New Jersey, Wood was awarded two Purple Hearts for his participation in the Normandy invasion. Wood took Semple’s place by the end of Mar. With the rest of the crew, and they completed a valid drop on Apr. 2 avoiding getting out of the competition.

Aside from these droppings in the desert, there were another three tests to be made before departing to the Pacific. These were long scale tests and required the help of many of the Task Group’s aircraft from Operation Crossroads and of the Manhattan District. The first two took place on Mar. 8 and 9, respectively, and the third on the 14.

Operation Zebra

This last one, known as Operation Zebra, set a more realistic scenario. While the first two took place on Albuquerque’s bombing range, the third was a hundred miles offshore of San Diego’s coast. The mission consisted of a simulacrum of the actual bombing elements and procedures to take place in Bikini. As such, they used an actual Fatman bomb (of course, without nuclear components).

Aside from the B-29 carrying the bomb, another three from Kirtland Air Force Base took part in the operation. These additional B-29 carried and deployed pressure recording instruments.

One of these B-29, though, had to abort its participation at the start of the operation. Also, eight F-13 from the Roswell Base were summoned for photographing the test.

A Landing Craft Infantry or LCI was the U.S. Navy’s chosen target. Yet, due to weather conditions, it had to wait until the next day to start the operation.

When the time of the operation came, the LCI proved to be not an easy target to find. It was but a little thing on the immensity of open waters and its whitecaps and waves. Radars, for their part, couldn’t be used, so bombardiers had to rely on coordinates rather than sight.

According to the measurements, the bomb exploded 1,000 feet before reaching the water. In terms of testing the equipment and the mechanism of the operation, the engineers of Manhattan District were pleased. They agreed that Operation Zebra’s outcome was richer than that of the tests made at Albuquerque.

During this time, on 22 Mar., the Eatherly-Wey crew was dismissed from the competition. Their drops finished always in the last place, as no one even made it to the 500-feet error mark. In fact, three of them were as off-target as more than 1,000 feet.

Kwajalein

As we said earlier, the second phase of training took place not in the mainland U.S. but in the Pacific. The initial scenario was to be Bikini Atoll itself.

Yet, the wind, highly unpredictable at all altitudes, was not on the test’s side. It was hard for navigating and ballistic correction. The cloud-capped sky didn’t help, neither the very few ground checkpoints available.

The crews didn’t take long to notice, though, that droppings’ accuracy was way lower than the marks made in Albuquerque.

From May 11 to Jun. 14 training continued at Kwajalein Atoll. Shortly after, Ramey, at arriving at Pearl Harbor on May 14, saw the performance reports. He was not happy with how the tests were going.

Ramey’s own analysts made their way to the tests’ atoll and take a look at Holloway’s bombing tables. On May 28, Kepner arrived at Kwajalein and caught up with the situation. He concluded that the bad results were related to poor visibility along with the previous interruption of training in Apr.

Yet, the main problem was the wind. The local wind, to be precise.

Despite the little time they had, analysts came up with a detailed study of atoll wind shears by Jun. 8, only 23 days before Able detonation. With this data, bombardiers were able to adjust their sight according to the wind properties. As a result, the tests’ marks improved greatly.

These last days, between Jun. 11 and 14, the teams completed 25 drops. To Ramey, the time to finish the competition started by the end of May. Only a month away from the start of Operation Crossroads.

The crew selection

The decision was of critical importance for Task Group 1.5 as well as for the Joint Task Force. In fact, for the whole Air Force reputation. Even the U.S. Armed Forces’ public image could be damaged, considering that the whole operation has cost an enormous amount of money.

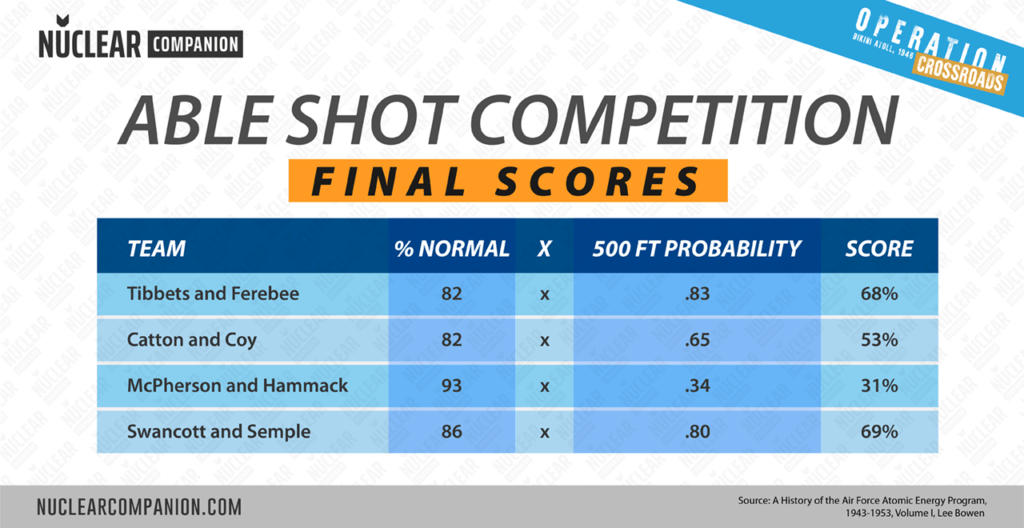

The objective of the test was to achieve the 500-feet accuracy mark. Failure was not an option.

On Jun. 13, Ramey received Blanchard’s word on the matter. In other words, his recommendation for declaring Swancutt-Wood’s crew as the winner of the competition.

Blanchard justified his decision in the fact that Swancutt’s crew had the privilege of having worked with Semple and learned a lot from him. At the same time, Blanchard acknowledged that Wood himself had a long record of experience as a bombardier.

To Blanchard, Wood was in fact not a mere replacement but a perfect addition. He considered remarkable Wood’s character of facing adversity and his curiosity for learning. On a technical level, he recognized him as exceptional in following bombing procedures.

Lastly, Blanchard suggested Col. Tibbets’ crew be the backup crew. This was, of course, in case the last tests for the next days didn’t change anything, and this wasn’t the case. The subsequent three drops made on Jun. 14 resulted in the confirmation of Blanchard’s recommendation.

The next day, Ramsey presided a meeting exclusively for the members of the participating crews and for the Operations Staff. He then announced Swancutt, Woodrow, and the rest of their crew as winners.

It’s worth noticing that despite being the favorite, Enola Gay’s crew was not the winner. Tibbets stated later that on paper he had actually won the competition, yet the test was rigged. According to him, test droppings’ results were deliberately altered for displacing him from the first place.

Tibbets said that in the droppings from 30,000 ft. he averaged an error of only 237ft. These numbers would have put him and his crew even above B-29 Norden bombsight’s capacity itself and above the rest of the participants. Yet, he declared that his score was affected by the inclusion of “ballistic wind” into the equation, putting him and his crew in the last place.

Going back to Swancutt-Wood’s crew, considering their abilities and experience we cannot think of the underdog. In fact, in facing the death of Semple by continuing with the competition they showed great tenacity.

At receiving the news of their winning, they decided to rename the crew’s B-29 (no. 354) as Dave’s Dream, honoring deceased Captain Semple.

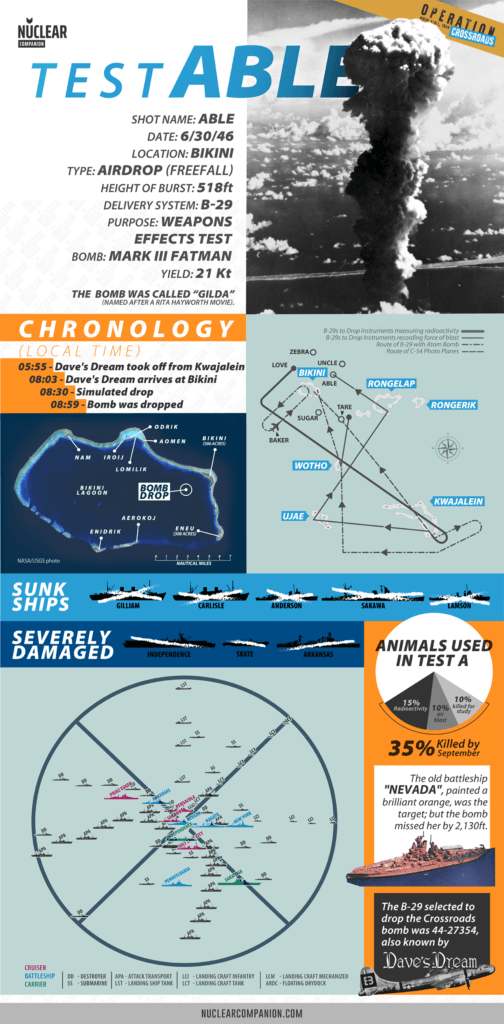

Test ABLE

Preparation

As the day for Test Able approached, all ships had arrived at Bikini Atoll. 92 US and 3 foreign ships of all forms and sizes.

The smallest ships were concrete barges and 36-foot large landing crafts. Among the largest were cruisers, five battleships, and submarines. There were even two carriers, including 888-foot Saratoga.

Some of them were surviving ships from almost all relevant World War II naval battles. The list includes Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, Midway, Leyte Gulf, the Solomons, the Aleutians, and the Bismarck breakout.

Considering its size, at the time the target fleet was the fifth largest in the world. Yet, this fleet wasn’t in form for battle.

Some of these ships had several instruments for measuring the explosion’s shock wave power and velocity. For this task, the navy made use of 5,000 pressure gauges, 25 radiation measuring instruments, 750 cameras, and 4 TV transmitters.

Yes, TV transmitters. Due to its importance and singularity, Able Day was on live television and radio worldwide.

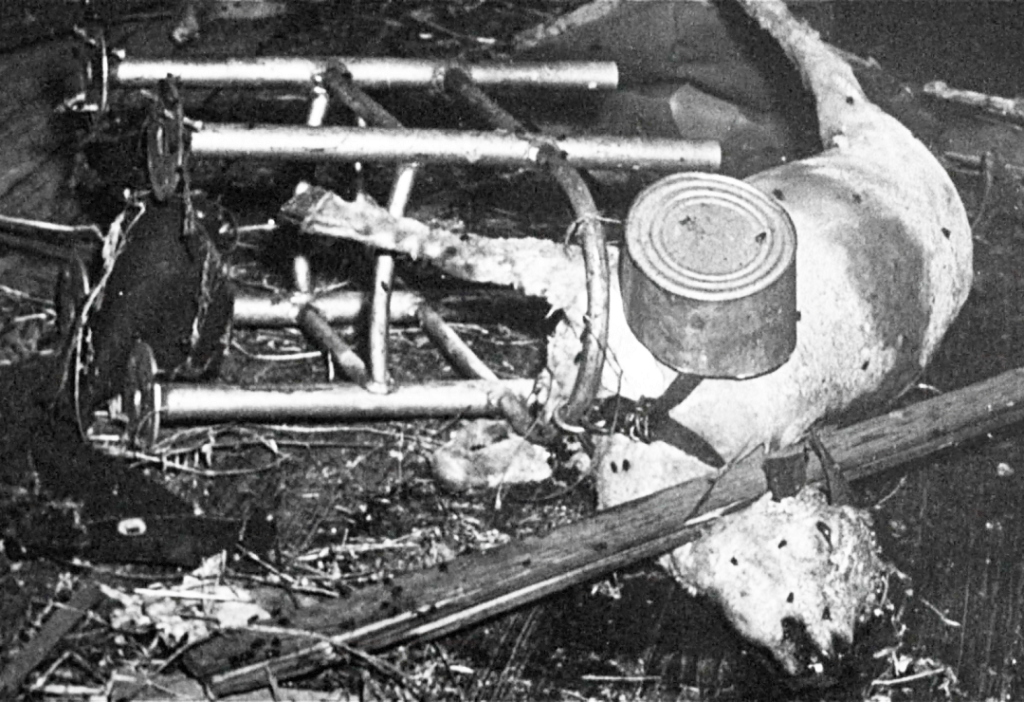

At the same time, the navy loaded 22 ships with fuel, ammunition, and all sorts of equipment. They wanted to know how would radiation affect not only warships themselves but also what you would expect to see inside of them. Things like radios, fire extinguishers, telephones or gas masks, watches, uniforms, and canned and frozen food.

Even heavy vehicles like tanks, tractors, and airplanes had their place on these ships. A total of 71 airplanes, to be precise, including two tied up seaplanes. All these extra objects accounted for a total of 220 tons of weight.

The U.S Navy set ships of every category at different distances, from the closest to the explosion to 4000 yards away. This was to learn how similar ships would take damage at different distances.

23 ships were within the 1,000-yard radius of the explosion. Arriving at Bikini in the last days of May, Battleship Nevada was the chosen target for the dropping. As we said earlier, for making a better target, it was painted bright chromite red and orange.

Support ships, for their part, were gone from Bikini on the sunset of Jun. 30, the day before the test. They went to their positions for the test: around 15 miles off Bikini from east to northeast. These positions used car models as codenames, e.g. Hudson, Packard, Soto, and Studebaker.

Just hours later, by midnight, the bomb was load into its bomber in Kwajalein. This was, as we said earlier, B-29 “Dave’s Dream”, number 44-27534.

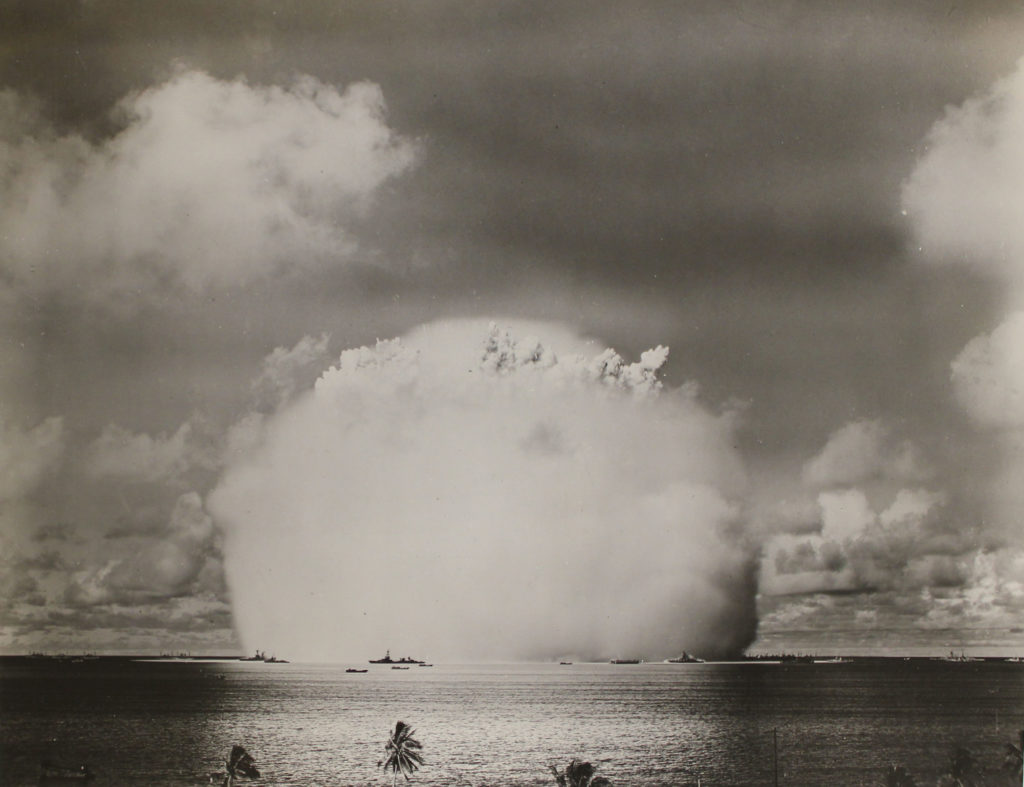

Bomb away, and falling!

Early in the morning of July 1, at five to six, to be precise, the bomb began its flight and reached Bikini at three past eight at an altitude of 32,000ft.

Following Dave’s Dream for scientific purposes were other aircraft. These were U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats and U.S. Army B-17 Flying Fortresses drones we mentioned before. Along with them were also 79 aircraft around the atoll, some of which carried VIPs and press members.

All was in place to start, but Dave’s Dream made a few practices runs before the actual bombing.

The first practice run was for checking wind velocity by radio from the aerological group. The second, at twenty past eight, was timed by a radar beacon from 50 miles away. This was for the plane crew for making adjustments for meeting the studied approach time and course.

This last practice bombing took place at twenty-nine to nine. The bombing crew had the additional help of a flashing lamp on Nevada. The visibility was perfect.

By this time, all crews of the operation were on deck, ready for watching the actual bombarding. At ten to nine, 50 miles from its target, Dave’s dream began its flight for the bombing run.

In Appalachian were also the media ready for covering the story. Cloth swatches on plywood sheets server for facing the blast. They also had special goggles for the blinding-intensity of the explosion.

Just seconds before 9 o’clock, Wood announced by radio:

“Mark! Bomb away, bomb away, bomb away, and falling!”

followed by other crew member’s:

“Listen, world, this is Crossroads!”

The bomb was dropped from 28,000ft.

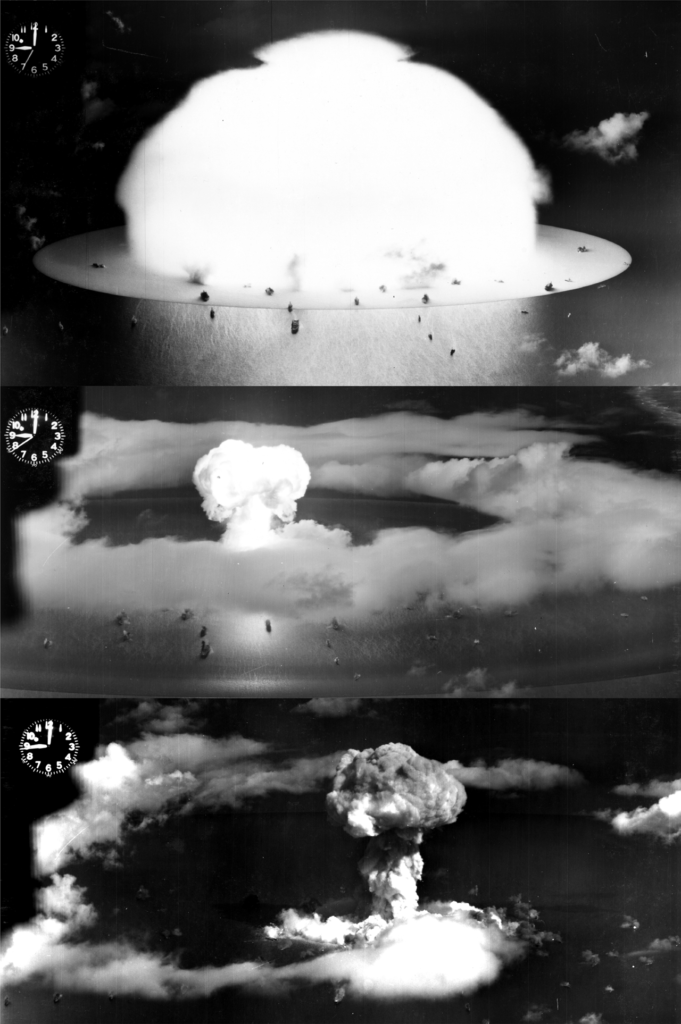

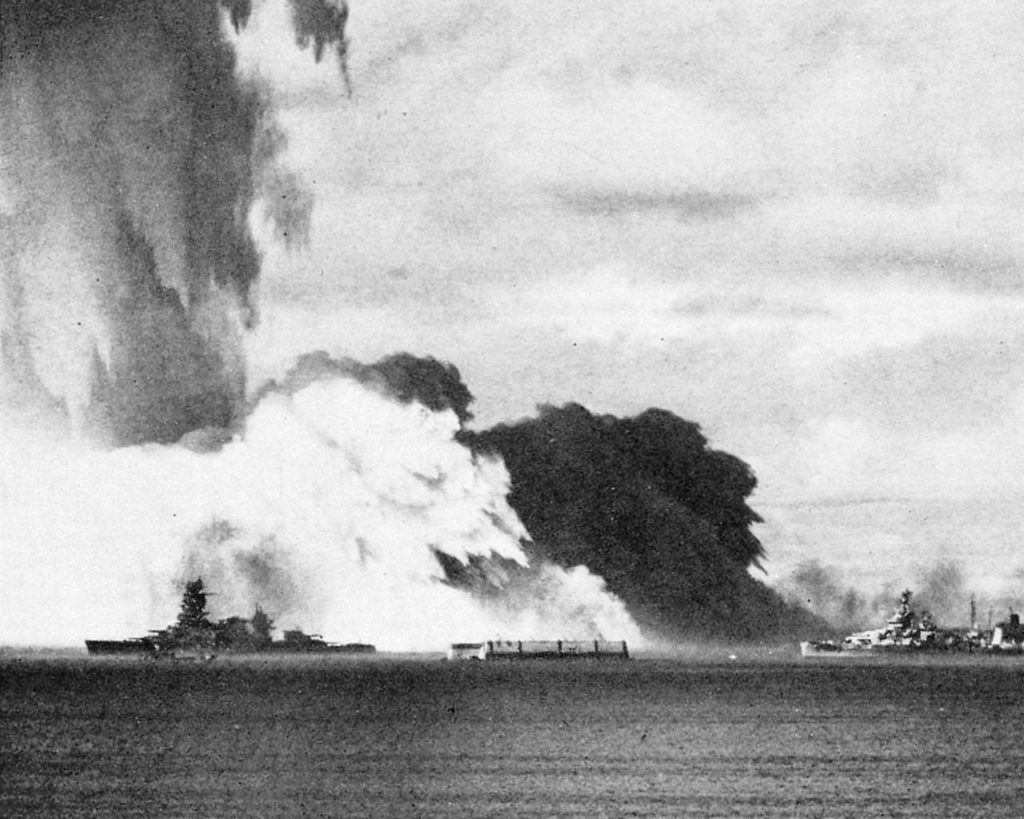

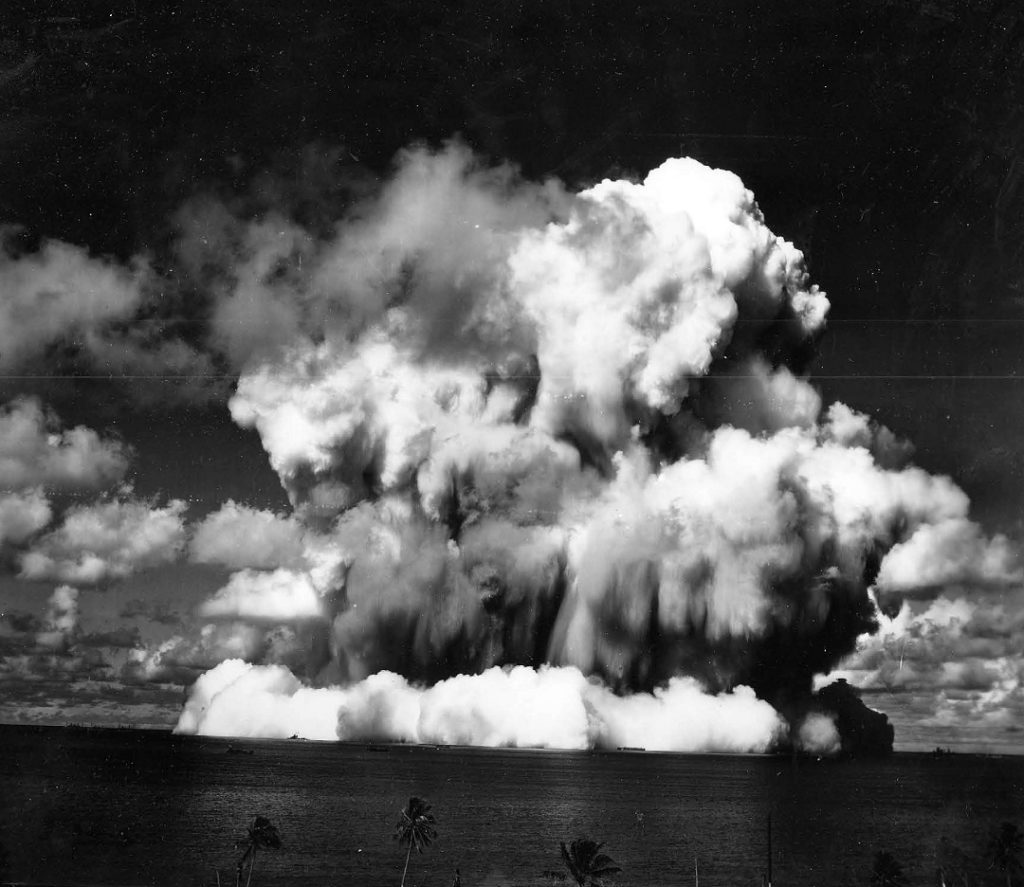

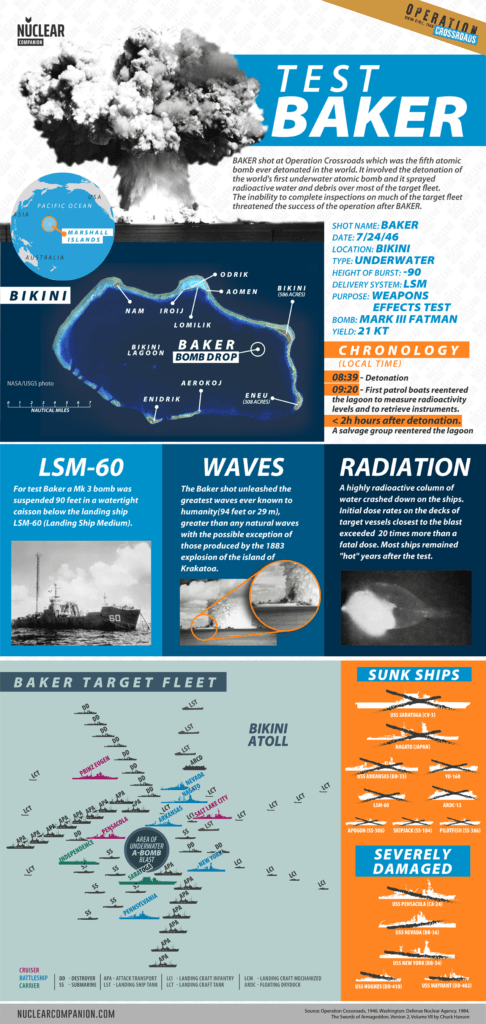

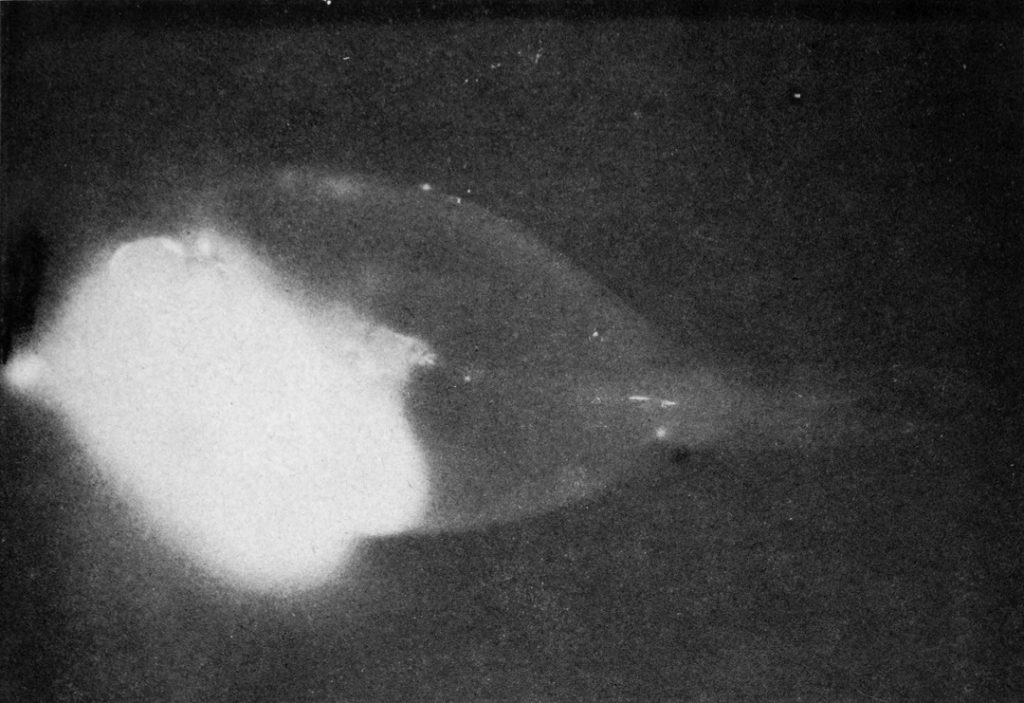

The explosion