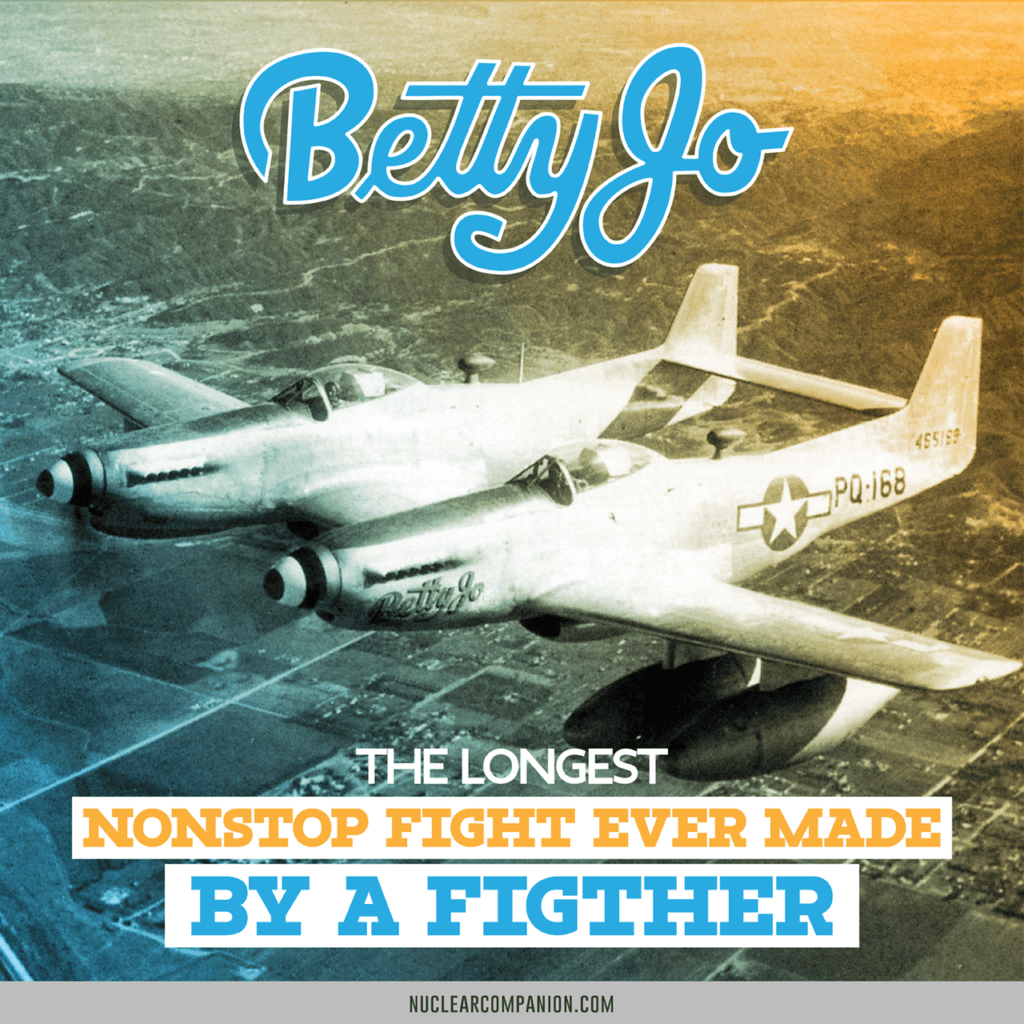

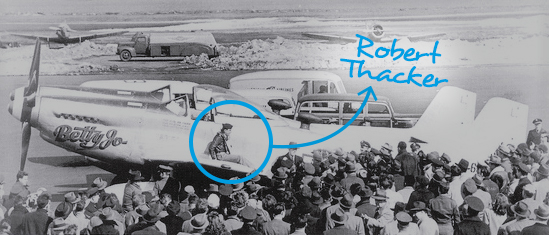

Today you’re going to see how in 1947 two pilots, Robert Thacker, and John Ard set a new record that still holds.

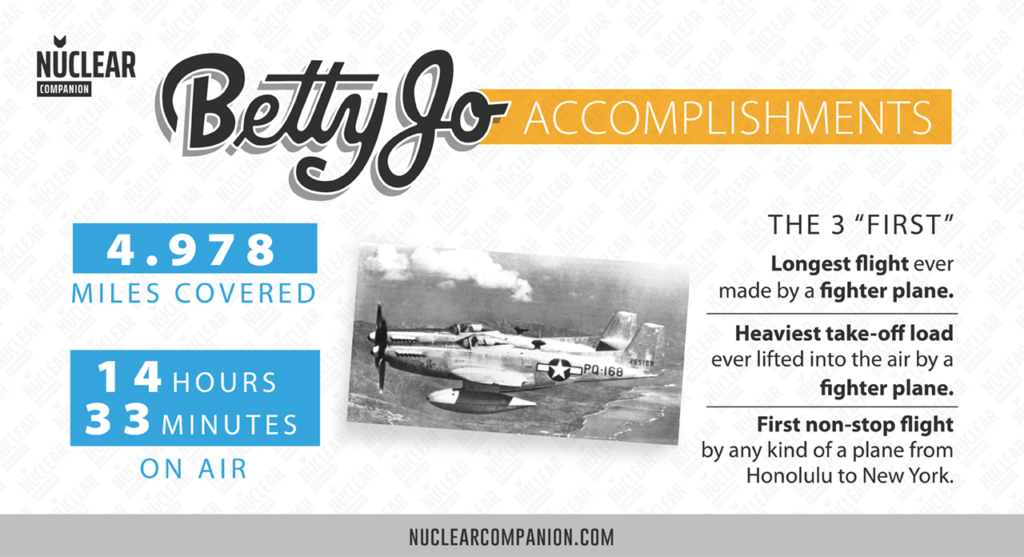

In an unprecedented event, they made the longest unrefueled nonstop flight ever flown by a piston-powered fighter aircraft.

The best part?

The plane used was an F-82 Twin Mustang. Possibly one of the oddest American aircraft to go into full production.

Sounds good? Let’s dive in.

The need for a new escort fighter

During the Second World War, the United States spent billions of dollars on mega projects.

One of these projects was the famous Manhattan Project to build an atomic bomb. It employed over 130,000 workers, took place in 30 secret sites and cost over 2 billion dollars.

But having the atomic bomb is not enough. You need to deliver the bomb to its target.

So, it would spend other billions in the production of superbombers to deliver them.

In fact:

The B-29 bomber was America’s most expensive weapon in World War II. And with its 3 billion dollars, it surpassed the Atomic Bomb.

But the United States still had another detail to solve:

The new bomber needed escorts fighters thought the flight in enemy territory.

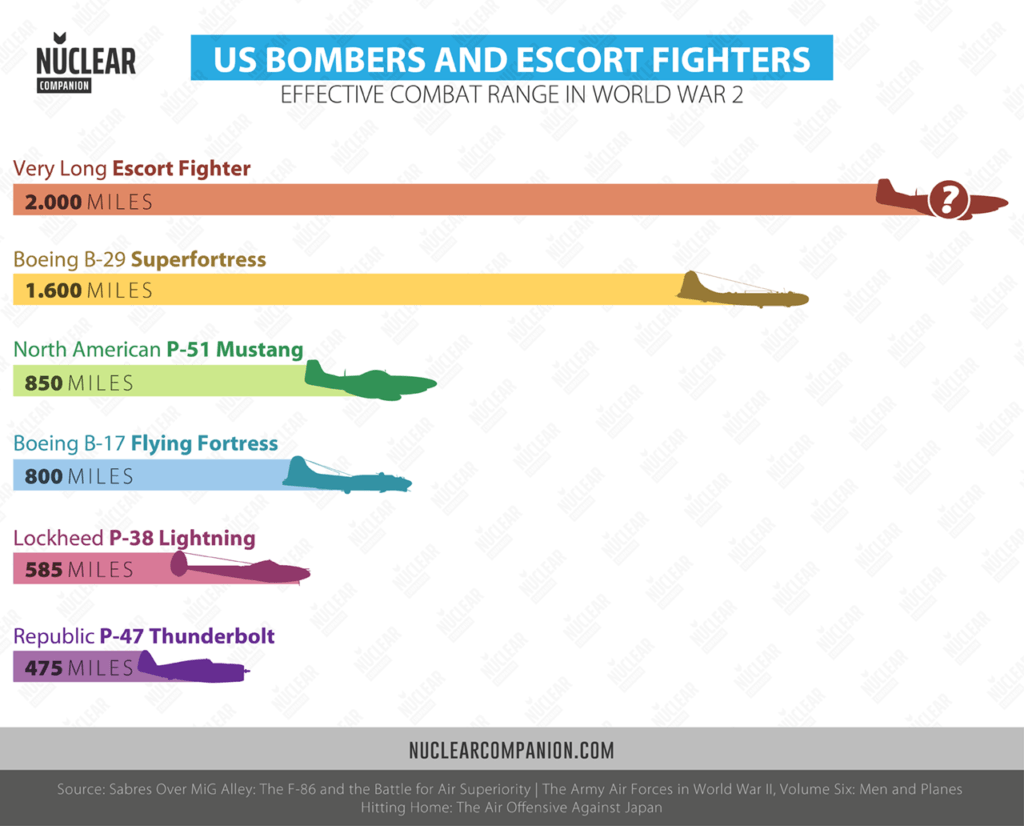

The Army Air Corps had capable fighters that could accomplish this mission in Europe. But it was another story in the Pacific Theater.

Indeed, the journey to Japan from the Philippines or the Solomons was a long one.

For example, the primary U.S. escort fighters were the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. But they could not make the round-trip without refueling nor could it fly at the desired altitude.

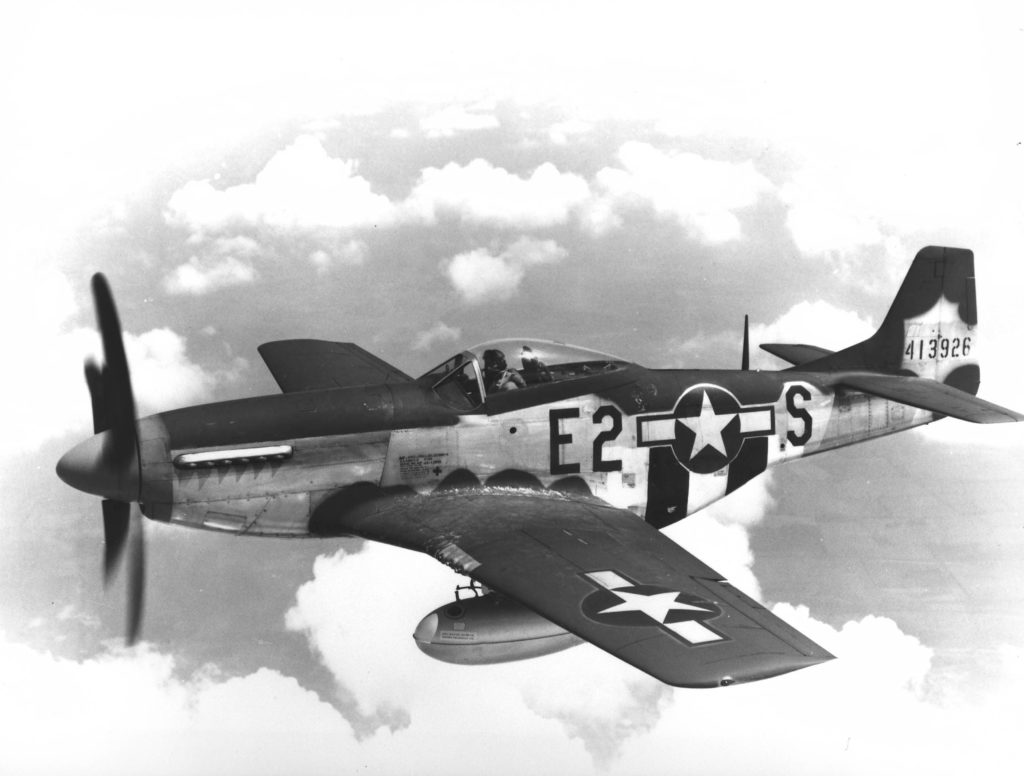

Neither could the famous Merlin-powered P-51 Mustang.

Could just the Army Air Corps add more firepower to the bombers to defend themselves?

It tried. The so-called “escort bombers”. But the result was disappointing.

Fewer bombs could be carried and they were less efficient than escorts fighters.

In short: It was necessary a whole new plane.

A plane that was fast and could cover 2,000 miles without refueling, while flying at above 30,000 feet.

And that leads us to…

The Birth of the P-82 Twin Mustang

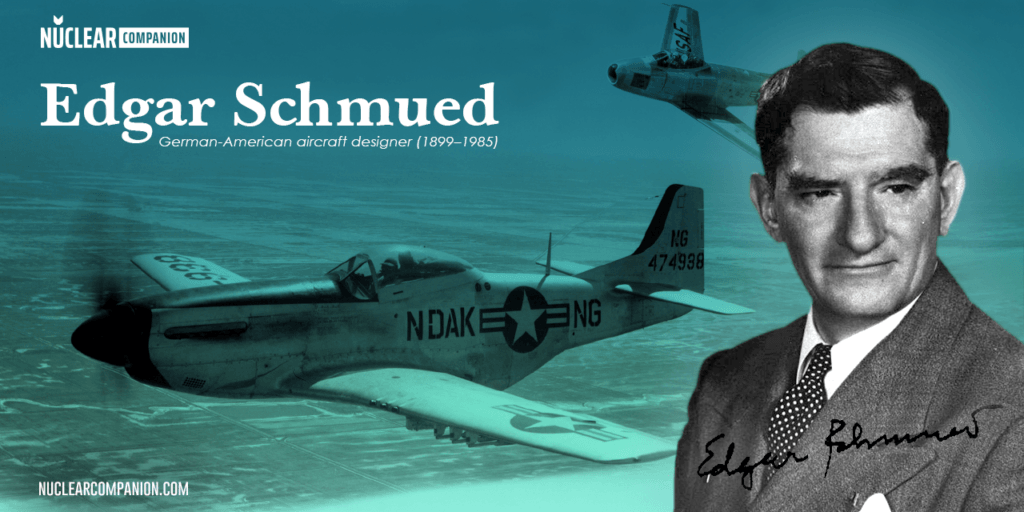

Edgar Schmued is one of America’s foremost aircraft designers. He designed classics like the P-51 Mustang, F-86 Sabre, F-100 Super Sabre, F-5 and T-38 Talon.

In 1935, years before he got his fame, a young Edgar O. Schmued had the idea to create an aircraft company. Together with some friends, he created a brochure that contained some planes designs. One of those was a twin-fuselage fighter.

In the end, he was not successful in creating his company and left the designs in his home.

Bur years later, working for North American Aviation, he found a way to revive his design.

Schmued had already established himself in the company.

In fact, he had risen to Chief of Preliminary design. The P-51 Mustang, one of his creations, would go on to bring down 5,000 enemy planes during WWII.

He presented his twin-fuselage fighter to the top directors, and it was a direct hit. And so in October 1943, work began on a very long range escort fighter.

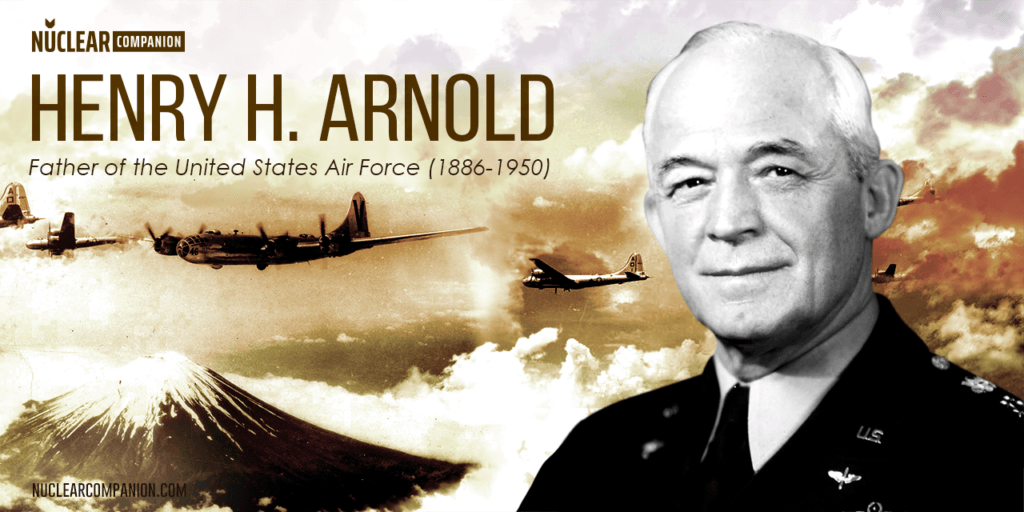

On January 7, 1944, General “Hap” Arnold, Commander of Army Air Forces (AAF) was visiting the plant. Schmued presented him the new proposal, and it was also an instant success.

As Schmued indicated the new aircraft advantages to Arnold:

- This plane would only need two pilots (The P-38 has a crew of three).

- Having two pilots would allow one to rest while the other is flying.

- If one pilot was to get injured during the flight, the other would see the mission through.

- Being the fuselages very close made the aircraft very maneuverable.

Did it work?

Some days later, the Army Air Force had already approved procurement of the new plane.

The name of the new fighter? P-82 Twin Mustang.

At a glance, it looked like two P-51 Mustangs joined together. But the internal structure would say otherwise. Beyond similarities, it was a new design.

Indeed, the engineers at North American Aviation did a very remarkable job:

- With a flight ceiling of 40,000 feet, the Twin Mustang could even fly higher than the planes it had to escort.

- Exceeding 2,000-mile range, they also had over delivered on distance.

- And the plane was fast – almost as fast as the P-51H, but had twice the range.

- The extra-wide plane had ample fuselage space and plenty of room for firepower.

It was already a historic achievement. But…

Too late to fight!

In August 1945 US drops the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrenders to the allied forces almost a month later. The war was over.

In November, NAA deliverers its firsts P-82Bs to the USAAF. Too late to show its high capabilities.

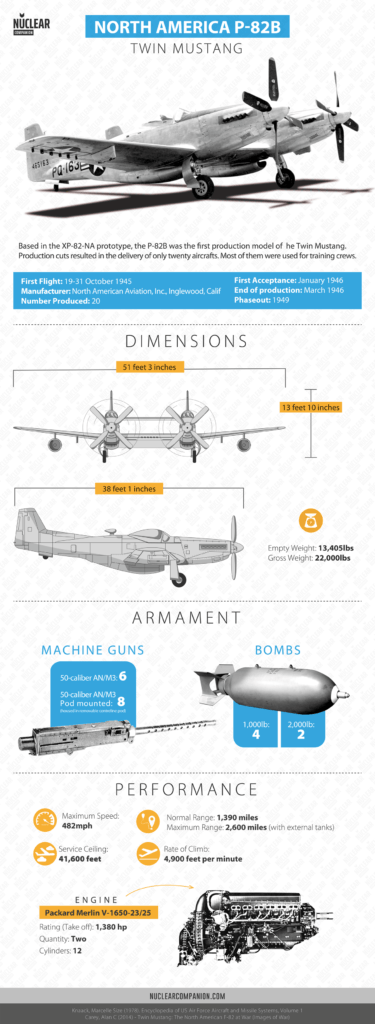

The P-82B was the first production version of the Twin Mustang. It had British Merlin engines and it was derived from the XP-82 prototype.

It would be the last piston-engine fighter made by NAA. And the last one bought by the United States Armed Air Forces (USAAF).

After the war ended, the USAAF brought down the order for the planes to only 20.

Two of these would get repurposed as interceptors and reclassified as P-82C and P-82D. The P-82Bs left didn’t get to field service as operational fighters.

Instead, the USAAF used them as trainers and guinea pigs, for different trials.

But it was at Wright Field testing ground that the P-82Bs true potential would shine.

Not Just Any Odd Plane

At the end of Wolrd War 2, Wright Field was the testing yard for the United States Armed Air Forces. More than 200 different types of aircraft were being tested there.

When the P-82 arrived at Wright Field, the USAAF didn’t doubt to push the new plane to its limits.

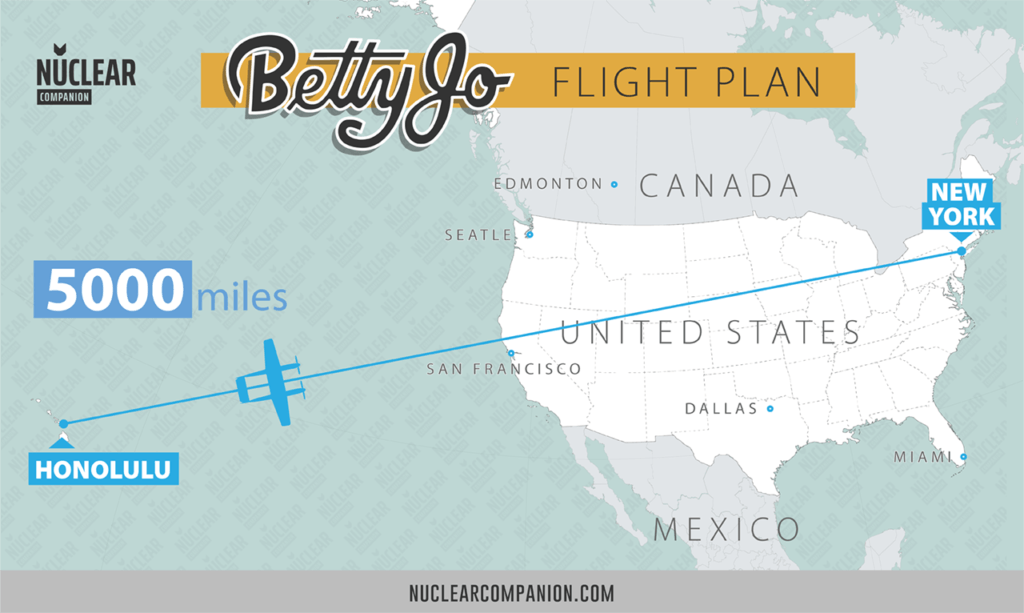

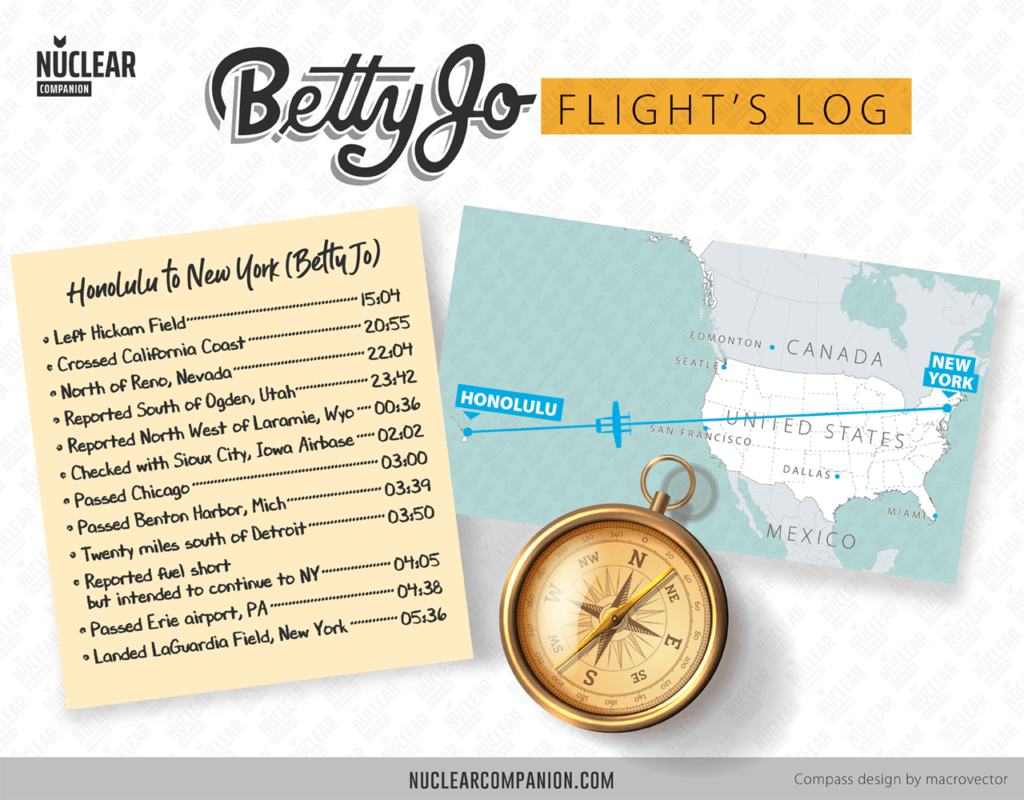

The Plan? Fly the P-82B all the way to New York from Hawaii.

In this way, the US would show its aerial superiority. This flight would prove that the Air Force was capable of protecting its bombers in the Soviet land.

North American Aviation (NAA) was also in need of positive publicity.

So, it would not be difficult to gain support from them.

The Coriolis Force

Why from Hawaii to New York? Why not a flight from east to west?

The reason is that prevailing winds at 20,000 feet are from the west. They can reach speeds as high as 60 to 100 miles an hour over the continental limits of the United States.

This is due to the deflection of the air caused by Coriolis force (rotation of the earth).

Meet the crew

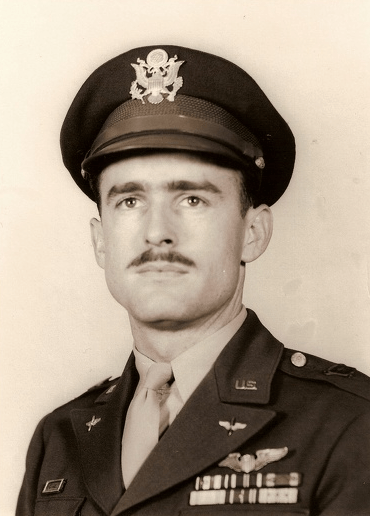

For the job, the Army Air Force choose Colonel Robert Eli Thacker. He was one of a few pilots who flew in both Europe and the Pacific theaters during World War II.

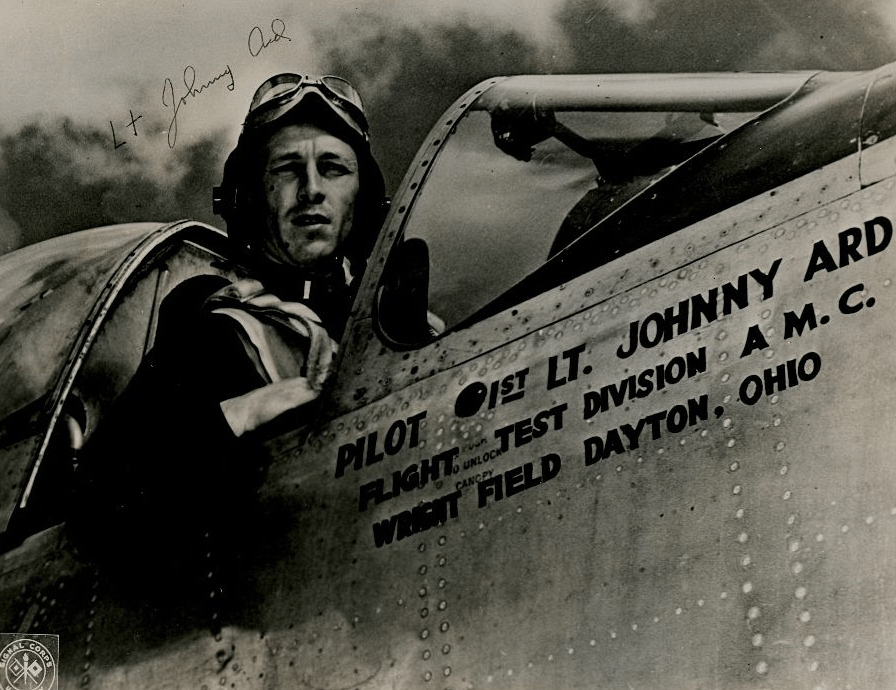

As co-pilot, Thacker chose 1st Lt. John M. Ard. He was assistant operations officer in the accelerated service test section

Ard who was from Inglewood, California, had fought with the Eighth air force as a fighter pilot. He had accumulated 270 combat hours.

The two pilots selected for the record attempt were exact opposites except physically.

The Colonel

With 3,000 flying hours on his back, Thacker was a confident, almost cocky, bomber pilot. He was a colorful extrovert 28-year-old with a wry sense of humor.

But, just let me go back some years before the flight. You really need to know Colonel Thacker Story.

Thacker passion for flying has been sky–high ever since he was a kid. At the age of 10, he already was a model aircraft leader in El Centro Central Union High School.

After graduating from Central Junior College with a major in engineering, he enlisted in the Air Corps as a flying cadet. He graduated as a second lieutenant in 1940 at Kelly Field, Texas.

Robert E. Thacker wearing his uniform. (Quentin Bland Collection, via 384thbombgroup.com)

His first assignment as an officer was to the 88th Reconnaissance Squadron. He relocated to the squadron base at Hamilton Field near San Francisco.

He didn’t know it, but his name was to gain soon some reputation…

On December 6, 1941, elements of 88th reconnaissance squadron left the continental US. They were to deliver several b-17 to the Philippines. The flight plan called for a fuel stop at Hawaii on December 7.

They didnt know it but they arrived in the peak of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Thacker flew through anti-aircraft and enemy machine gun fire to land at Hickam. He only blew a tire during the landing.

Next, he served in the Pacific Theater of Operations, where he flew 44 missions as a B-17 pilot. And He was one of the pilots who helped evacuate MacArthur’s staff from the Philippines.

In total, the Coronel logged more than 420 combat hours before returning to the US in December 1942.

He returned as commanding officer of the 88th Recon Squadron. For the next seven months, he trained B-17 crews.

But stay with me.

He felt he could do more to help win the war… and he volunteered for service in Europe.

There, he joined the Eighth Air Force in England. So, he served as deputy commander of the 384th Bomb Group, First Bomb Division.

16 August 1944, Delitzsch airfield. Thacker as Commander of the crew of the 44-8007 Screaming Eagle (Quentin Bland Collection, via 384thbombgroup.com)

He flew 30 missions over Europe before returning to the United States.

Finally, the end of the war found him awaiting rotation back to the Pacific.

In 1945, he became commander of the accelerated service test section at Wright Field, Ohio.

He became one of the first men in the Air Force to fly a jet aircraft when he tested the Bell P-59 Airacomet. Also, he tested or was under his supervision the F-80 Shooting Star and the P-51H.

Then, the P-82 arrived…

The fighter pilot

Ard was a shy 26-year-old fighter pilot. He was quiet, rarely said a word and would blend with the background.

But the Armay Air Forces had rated him as one of top experts on fighter planes.

John was born in Hawarden, Iowa on 18 October 1920. His father, James Alden Ard of Tyler-town, Minn., was a telegraph operator. Her mother was Adrianne “Ada” Mieras.

He graduated from high school in Maurice, Iowa in 1939. Shortly Afterward, he moved to California. There, he studied for one year at Compton Junio College.

Ard enlisted in the Air Force in September 1942. He received his wings and commission in December 1943.

He was assigned to the thunderbolt 353rd fighter group at RAF Raydon, an Eight AAF fighter station in England. On November 1944, John ended his tour of duty over Europe.

In total, John had engaged in 68 missions and 270 combat hours. He was credited with downing three enemy planes.

353rd Fighter Group During the Second World War

“Flying P-47D Thunderbolts and later P-51D Mustangs the 353rd’s appearance in the skies over occupied Europe witnessed growing American air power and helped to change the course of the air war.

From mid-1943 until the end of hostilities in Europe, the 353rd participated in all major aerial battles from the 1943 Regensburg and Schweinfurt raids to ‘Big Week’, the attacks on Berlin, and the support of the D-Day landings and Normandy campaign in 1944.

They went on to win the Distinguished Unit Citation during the Arnhem operation of September 1944 and after converting to P-51 Mustangs they continued to play a full and prominent role in the final smashing of the Third Reich from the air.”

from Graham Cross – “Slybirds: A Photographic Odyssey of the 353rd Fighter Group During the Second World War”

For this service, he received four Oak Leaf Clusters besides his Air Medal.

He won his decorations for “exceptionally meritorious service in aerial flight over enemy occupied Continental Europe. The courage and skill displayed by this officer reflect great credit upon himself and the armed forces of the United States.”

Since his return to the United States in December 1944, he served as an army test pilot at Dayton, O.

On May

The “flying gas tank” “

The flight “cooked” for six months.

First, they needed a plane.

The chosen one was P-82B USAF s/n 44-65168. Lt. Col Thacker named it “Betty Jo” after his wife, the former Betty Jo Smoot of Palm Springs.

But, NAA misspelled the name of the aircraft as ‘Betty Joe’. And the plane went through a lot of publicity shots before it was finally corrected.

Now, the distance that Betty Jo was to cover between Hawaii and New York was about 5,000 miles. It just could not do it in “combat” conditions.

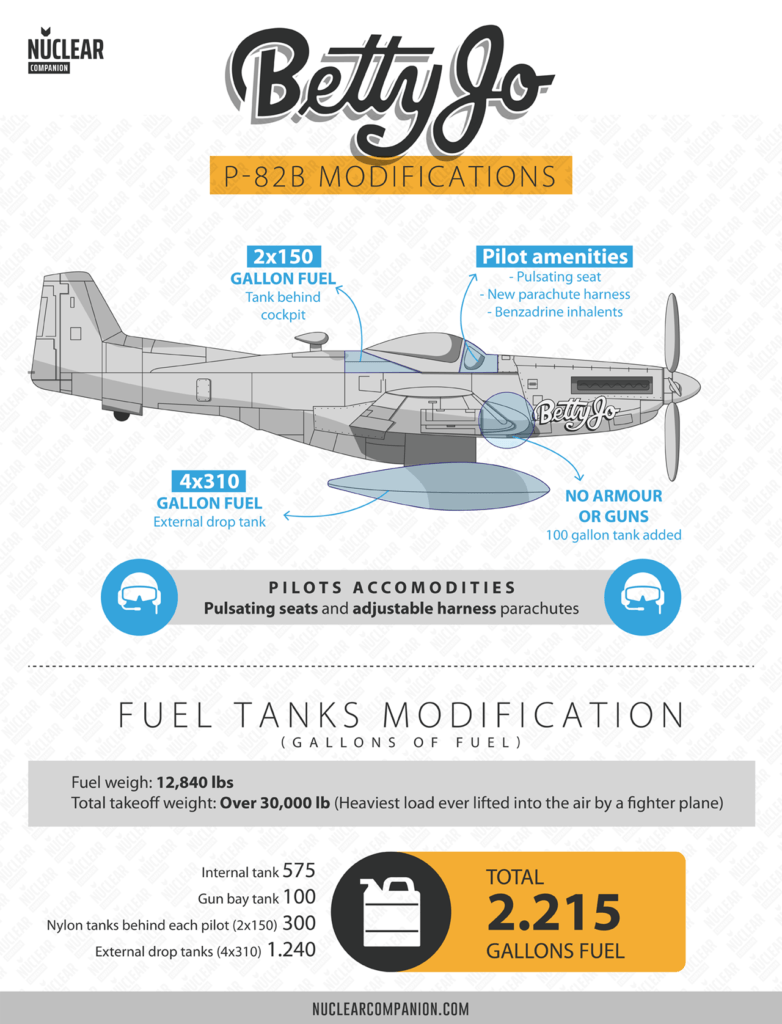

So, NAA had to make some changes to the aircraft to reach that range. Literally convert Betty Jo in a “flying gas tank”:

- No armor nor guns were left.

- A 100-gallon fuel tank in the gun bay.

- Behind each pilot would be a 150-gallon Nylon fuel tank.

- Underneath the plane, it would carry four external 310-gallon drop tanks

The Nylons tanks were rather new to the Air Force. They expand when filled with gasoline and contract as the fuel flows out.

All this would bring total fuel to 2,215 gallons.

All this fuel weighted 12,840 lbs. And this made for a total takeoff weight of over 30,000 lb, which was 5,000 lb beyond the maximum load capacity.

The drop tanks were only to be in the plane as long as they were useful. The pilots will drop them as soon as the plane spents its fuel.

They calculated that they would release the first two external tanks 1,800 miles from Hawaii. The remaining two on the city park at Laramie, Wyoming.

But NAA made Further adjustments to the materials and equipment on-board. These changes would make the flight bearable for the pilots:

- Pulsating seats

- A new design of parachute harness

- A benzadrine inhalent, instead of tablets, to keep them awake.

The seats, designed to ease the strain of long hours in a sitting position, expand and inlate automatically. Thisy way, they keeping circulation going in the back and posterior.

The parachutes had adjustable harness leg straps. These kept loose during the flight. In case of an emergency, a quick pull in two cords would tighten them for quick operation.

Thacker and Ard wanted to make sure the plane could do the flight. Both pilots took the aircraft on a number of test-hops in California as in the following picture during 1946.

“One long sit”

On 27 January 1947, the Army Air Force revealed the projected distance record in a press conference. On it, Thacker and Ard told the plan for the forthcoming attempt.

“Compared to a combar mission, this will be just one long sit”, Colonel Thacker said.

“This is no a glamor trip, but a research flight to determine the P-82’s ability to escort long-range bomber missions.”

They told they planned to make the long flight in less than 16 hours at a speed approaching a 370 mph. average.

Since Betty Jo had no autopilot both pilots would alternate hourly on the flying chore.

Also, sleep for the fliers would be imposible as they will be on oxygen during the entire trip. A trip without food and on instruments for at least five hours.

olonel Thacker would handle the navigation and keep the flight data on cruise control and engine performance.

This way, the Air Material Command would use this data to study long-range flight problems.

After reaching California, Betty Jo was to follow the great-circle route. She would cruise over Reno, Nevada; Rock Springs, Wyoming; Detroit, Michigan, and Erie, Pennsylvania.

No definitive date had been set but the Colonel would take Betty Jo for Honolulu, about February 5. Then leave Hickam Field for New York as close to February 10 as possible.

Aloha Hawaii

On February 12 of 1947, Thacker and Ard flew the plane from California to Honolulu, Hawaii. They departed from Muroc Army Air Base and arrived at Hickam Field at 6:04 on Wednesday evening.

SIDENOTE: In 1949, Muroc Army Air Base would became Edwards Air Force Base.

The plane made the Pacific flight in 11 hours and 43 minutes. They flew at 10,000 feet and a ground speed of 235 miles an hour.

This westward crossing was the first transoceanic flight by a fighter type arcraft. It was described by both pilots as “very comfortable”.

But, she didn’t fly alone. A B-29 accompanied Betty Jo, the “Pacusan Dreamboat”, loaded with spare parts.

The Pacusan Dreamboat

On 20 November 1945, this historic modified B-29 (44-84061) broke the distance record. It made it from Guam to Washington DC in 35hr and 5 minutes.

Next year, on October 4-6 1946, it flew from Hawaii to Cario by way of the North Pole in 39 hours 35 minutes. It provided useful information for long-range flights across polar routes.

Betty Jo’s flight marked the first spectacular army airforces since then.

The B-29 also carried army technicians, and a civilian factory representative. They would help make ready the twin mustang for her record hop.

At the “Pacusan Dreamboat”‘s controls was Col. Alfred Boyd. He was the project engineer for the Honolulu-New York record.

Brig. Gen. Donald E. Stance, commanding general of the 7th Air Force, greeted the pilots. And greeting them, was Col. Thomas H. Chapman, commander of the Hawaiian Air Material area.

Then, they waited for the first favorable break in the weather to take off. The date of the flight had to be changed three times, due to adverse weather conditions.

In the end, Thacker waited in Hawaii for two weeks until he had a 20-knot tailwind

Take off at last

The day was February 27th, 1947.

The skies were clear and Betty Jo had parked at the southwest end of Hickam field.

“We’ll make it in less than 15 hours”, Colonel Thacker said before he climbed into his portside cockpit.

Like Ard, he had leis of carnations around his neck. They were in high spirits and seemed confident of success.

At 3.04 p.m. of Hawai, Betty jo started moving with Lt. Col Robert E. Thacker and his co-pilot Lt. John M. Ard. Thirty-nine seconds later and more than a mile down the runway, it took-off.

Brig. Gen. Donald F. Stace, commander of the 7th Air Force and hundreds of spectators watched the plane to get away.

They headed toward the Koolau mountains. Then, Betty Jo passed over Pearl Harbor and continue over downtown Honolulu. They disappeared into the ocean after they passed over Diamon Head.

Thirteen minutes after takeoff, Robert reported the Betty Jo was up to 13,000 feet and climbing.

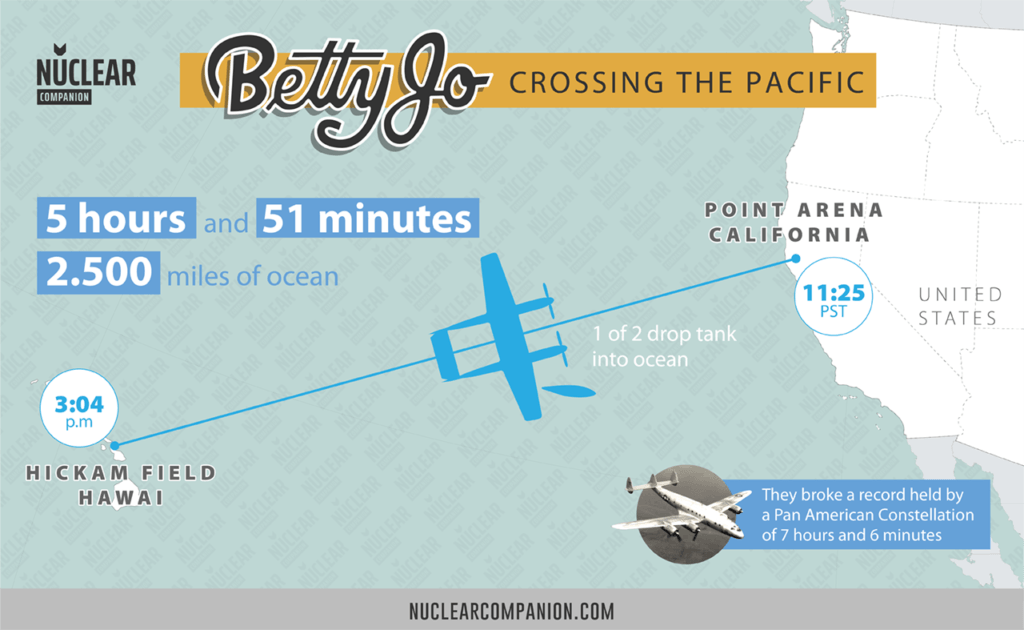

Crossing the Pacific

Three and a half hours later, Betty Jo reported her position. It was 60 miles north of a rescue vessel stationed midway between Honolulu and San Francisco.

She reported making excellent time, with a ground speed of 348 miles an hour.

After exhausting the outer external drop tanks they attempted to release them. But, they had difficulties dropping them into the sea.

Hopefully, the left wing tank was dropped near California’s coast. But the right wing one stayed.

This caused a drag that held the Betty-Jo’s airspeed below 400 miles per hour. The Colonel put his leg over the stick for leverage.

The Oakland municipal airport control tower was the first contact on the Pacific coast. Thacker and Ard reported crossing the California coastline in darkness.

They were 125 miles north of San Francisco, in Point Arena at 20,000 feet. Time was 11:25 PST.

Thanks to a strong tailwind the Pacific flight lasted 5 hours and 51 minutes. To reach the coast of California they spanned 2,483 miles of ocean.

Doing so, they broke a record held by a Pan American Constellation of 7 hours and 6 minutes.

They still had 2,568 miles to go in the circle route to New York.

The great-circle route

The plane hit the coast about 17 miles south of Point Arena flying at 20.000 feet, with” a strong tailwind.

It crossed Sonoma county and dashed on between Fairfield and Williams on route to Reno.

It crossed Nevada passing north of Reno at 1 a.m. PST.

At 3:12 am MST, the plane checked with Hill Field control tower while passing 45 miles south of Ogden. She reported 440 miles per hour.

At 6:06 am New York time, the Betty jo was 85 miles north of Laramie wy, flying on instruments at 22,000 feet.

The plane hit another snag when it got to its second drop point near Laramie, Wyoming, as the third and fourth tanks failed to drop.

But, the most serious malfunction was the failure of Ard cabin heat. He would not have heat during half of the flight. And also, his cockpit instruments became ineffective which rendered the navigational instruments useless.

It passed over Sioux City at 6:32 am. It communicated with the Municipal airport who got its position and gave some weather data.

Fuel worries

Roaring eastward over the great plains, the ship swept over Chicago at 6:49 am, hitting a ground speed of 320 miles an hour.

Soon afterward, Thacker, announced theirs worries over the radio.

The extra drag of the empty tanks was reducing their speed below the 400 miles which he had hoped to average.

Also, Betty Jo had consumed more fuel than the planned over the Pacific, he said.

He also indicated that they might seek to land in other fields.

The authorities alerted the airports along the route. At small airports across Ohio and Pennsylvania, men gazed at the sky. They expected the flight to end in their own fields.

When Betty Jo got to Pennsylvania, it met headwinds of 65-miles-per-hour. It decreased its speed even further.

So, Thacker considered coming down at Wilkes-Barre, Pa. But Ard insisted, “Colonel, we can do it”. And they decided to shoot for La Guardia Field.

We’re going to take a shot at New York,” they said by radio over western Pennsylvania.

Emergency equipment lined the runway of La Guardia Field. They prepared themselves for an emergency landing.

“Hey, look out! That’s my wife! ”

With only 60 gallons of gas left, on the 28th of February, 1947, at 11.06 a.m., Betty Jo landed at La Guardia Field in New York.

It had enough gas for only another half-hour of flight.

As they landed, a large crowd of people watched its arrival. It consisted of friends, military officials, and the press.

When Betty Jo taxied to a standstill, Thacker jump to a wing, he was looking for his wife.

Ard stood frozen on his seat. He was stiff and couldn’t get out of the plane for several minutes.

“Hey, look out!” Thacker cried, leaping to the ground, “That’s my wife!

He put his arms around Betty Jo and kissed her.

Lt. Ard also leaped to the ground, almost into the arms of his wife, Doris.

They deserved it:

They had flown 4,978 miles in 14 hours, 31 minutes and 50 seconds for a new world record.

It was the longest ever non-stop flight by a propeller-driven fighter.

And, this flight was more than twice the greatest distance flown by any fighter on a mission during World War II.

The average speed was an incredible 342 miles per hour. But the drag caused by the drop tanks had slowed the plane down by 25-30 miles per hour.

Despite this, the flight landed 29 minutes ahead of schedule. It was fortunate as the plane was almost out of gas.

“There was nothing heroic about it,’’ Colonel Thacker told newsmen as he rubbed his tired eyes. “There was nothing to it. Please don’t make a hero out of me.”

Both Lt. Col Robert E. Thacker and Lt. John M. Ard received the Distinguished Flying Cross. Betty Jo had made its owners proud and had proven what it could do. Other personnel that worked on the operation also received commendations.

One thing they had to do when arriving was to try a new K ration. The goal was to see whether it was effective in restoring energy after the fatiguing mission.

But, that experiment never came off. Soon after the plane landed in New York, someone in the crowd lifted the rations as souvenirs.

What happened to Betty Jo?

Well, first she got a change in category.

In 1948 the recently formed Air Force changed the designation of the Twin Mustang from P-82 to F-82. The P standing for Pursuit and the F for Fighter. The new Fighter category covered more operations than the old one.

So, Betty Jo became an F-82 fighter.

Then, she would see no action during the Korean War, unlike other Twin Mustangs.

But, she would be instrumental in tests. In September 1950, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) acquired Betty Jo. She was re-designated as EF-82B, with the code NACA-132.

It was the third Twin Mustang acquired by NACA.

It would use her for ramjet studies at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. Which is now the NASA Glenn Research Center.

NACA placed the Ramjets in-between the two fuselages of Betty Jo for testing. She also would have to launch 16-inch missiles.

Seven years and a damaged wing later, NACA donated Betty Jo to the United States Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio.

For Betty Jo’s final flight was the trip to the museum. In that occasion, the pilots were Joseph S. Algranti and Andrew David Balazi.

She served as a static display outside the museum for the next fourteen years. In 1971, the Museum built a new building. And on the 17th of October, it moved Betty Jo to the Cold War gallery, where she remains to this day.

Equipment and clothing from the flight are also part of the display. Including the jacket worn by Lt. Col Thacker.

SIDENOTE: The Museum changed its name to

What Happened to our Heros?

After the flight, Colonel Thacker continued his colorful military career.

As a fighter pilot, he was successful. He had more than 1000 hours flying jets, and a had a record. But, as before, his primary interest was strategic bombers. Not fighters.

So, he graduated from the Air Command and General Staff School at Maxwell AFB, Alabama.

He also participated in the Korean War and Vietnam.

Finally, he retired from the Air Force in 1970.

He currently lives in San Clemente, California. There, he continues to this day his old passion for aircraft modeling.

Sad to say, his wife, the real Betty Jo, passed away in 2011 with 91-year-olds.

Ard continued as a test pilot for some years.

Then he retired from the Air Force and in 1954 he moved to Fort Pierce in Florida. There, he worked as a civil engineer with St. Lucie County until his retirement.

He died on 13th November 1997 in Fort Pierce. Ard was survived by his wife Doris; three sons: Randy, Dennis, and David and his daughter Sandra Pauley.

Now it is your turn

What do you think of Colonel Bob Thacker, John Ard and their record?

Or maybe you have a question.

Let me know by leaving a quick comment below right now.

Brilliant article. Couldn’t find anything as in-depth as this one.

Thanks Gab! Much appreciated. I still have to tweak some parts and add others (e.g. Bibliography).

John Ard was my Grandfather, my mother is Sandy. He was always helping people and as a child really allowed me to take things apart and put them back together.

He passed when I was 18 years old and I’m glad I got to learn from him.

Thanks Summer. This kind of comment is very important to me.

Your Grandfather is one of those unknown heroes that need more publicity for what they did.

Phenomenal article! Very informative. I was unaware of any of this information about the flight or the plane. I had heard about “Betty Jo” in response to a plane on a comedy show I love and I looked it up to understand the reference and found this page.

I just wanted to point out that there are a number of grammatical errors in the article from spelling to proper wording. You might want to get someone to proofread it to correct those problems. Otherwise, thanx a million for the info.

Thank Corey! I’m glad you enjoyed the article and I’m sorry you got to see any grammatical error. Thanks for pointing that out.

Hi, This was a very informative article that has made the family of John Ard proud. Just wanted to let you know you forgot Dennis Ard-his middle sons name! LOL!

Hi Wendy! Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it and that it could bring some light regarding John Ard’s life. His family really should be proud.

I checked my notes and John’s post AF life info came from an obituary in The Palm Beach Post from 1997 that incredibly doesn’t mention Dennis at all. 😀

I will add him. Thanks!

Great article ,I am Dennis Ard the second Son,somehow was left out of this information, the Drop tank released fine when they landed, Dad said Bob Thacker did not pull the right lever,have Original photos of Flight and Newspaper clippings,please contact me Paul Dent ,thank you Dennis Ard

Hi Dennis. You’re welcome. I have no words to describe how it feels about being contacted by John Ard’s family. I really enjoyed investigating and writing about your father. Any contribution to enriching his story is welcomed! Let me send you an email. Thanks!

I read Thatcher’s obituary today in the NY Times, and found your excellent research. Many thanks for it.

The New York Times reported in December 2020 that Robert Thacker died on November 25 at his home in San Clemente, CA. He was 102. The death was confirmed by his daughter. The Times obituary prompted me to do a Google search on the P-82 aircraft, and that search eventually led me to this article about the record-setting Honolulu-to-New York flight. What stood out for me, a four-decade former resident of Honolulu, was the time it took for the Betty Jo to reach the mainland — just under 6 hours from Hawaii. Passenger jets take about 5 hours today, so the tailwind for the propellor-driven plane on that flight was truly impressive. Thanks for this well-written article.

In the article about “Betty Jo”, there’s an unfortunate literal (that’s a proofreader’s name for a mistake). The word is “manurable”.

Oops!

Thanks John for commenting about it and sorry for the literal

Saw this amazing aircraft in person a few months ago. Did not know the story behind it. Amazing! Thank you for writing this, very enjoyable read.

Mr. Dent Thank you for taking the time to write about this historical flight. It ads a lot of meat to the bones of what I read on Wikpedia. They didn’t even mention Lt. Ard. Looks like Col Thacker chose the right day to make the flight, since they didn’t run into any weather until they were almost to their destination. Makes you wonder how much faster they would have been without the drop tanks that didn’t eject. That was a lot of extra drag. I’ve been a long time aircraft enthusiast and history buff, especially pertaining to aviation. I’ve been to Wright Pat and have pictures of Betty Jo buried in a shoe box somewhere in the house. It was a quick self guided tour as we were traveling from Virginia to California, so I did not know the particular history of that aircraft until today. Very cool. Again, thanks for the extra info, I’ll be sharing that with some of my aero-buff pals. Sincerely Jon Bybee Sacramento CA

I wish someone made a decal sheet for “Betty Joe!” I’m surprised since its in Dayton at the AF Museum that

no ones done so. Fabulous accomplishment to say the least.

I have Original Photos and News clipping still my Father Quit flying after being Black balled I am still very proud of my Dad , met Bob Hover and Dad use to say he was the best Pilot ever , talk with Pete Mitchell ,thank you Dennis Ard

really good stuff. thanks so much for doing the research necessary to produce such a great piece.

I have one comment about the take-off from Hawaii. I have given some thought to your description of the take-off, and this being an endurance flight, I thought I would comment on that portion of the flight. Depending on the direction of the take-off from Hickam AFB, and probably receiving clearance to “climb on course.” To adhere to this clearance, their route of flight would take them over Honolulu and Diamond Head. To fly over Pearl Harbor would require that they deviate from their, “climb on course” clearance, and waste precious fuel.

I’ll say again, great story. Great effort. P.S. in case you are curious, I am a retired USAF KC-135 Boom Operator

usaf

As a resident of San Clemente I would often see the Colonel out for his daily walks even approaching 100 he was doing 5 miles a day. My wife and I were driving one day towards the pier and I saw him walking and pulled up next to him to say hello. He came up to the car and reached in to take my wife’s hand and asked Is this your wife? He proceeded to tell me that I had married way over my head. Very much missed by all who knew him here.

Hey Paul,

Great job on this, and thank you for writing it.

My family and the Ard family have intertwined as my two older brothers and sister went to school with Randy, Dennis and Sandy. Then a few years later I met David one of the best friends anyone could have.

John was truly an AMERICAN HERO.

Thanks again for helping all to know.