Introduction

The United Kingdom’s Trident warhead equips the Royal Navy’s Vanguard-class submarines, armed with the Trident II D5 ballistic missiles. Designed by the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) at Aldermaston and Burghfield, this warhead closely follows the U.S. W76 warhead design.

Featuring selectable yield from less than one kiloton to 100 kilotons, the warhead utilizes the Mark 4 re-entry vehicle (RV) provided by the United States.

Between 200 and 225 warheads were produced, with the first batch completed in September 1992, in time for deployment aboard HMS Vanguard. Production costs escalated significantly from initial estimates of £250–£300 million to over £1 billion due to deficiencies in planning, control, and liaison with the main Trident program.

Current operationally available warheads number fewer than 160, sufficient to arm 48 missiles on three out of four Vanguard-class submarines. Typically, only one submarine is on patrol at any given time, carrying up to 48 warheads. In 2010, it was announced that operational warheads would be reduced to a maximum of 120, with 40 warheads on patrol at any given time.

The overall nuclear stockpile is expected to decrease to no more than 180 warheads by the mid-2020s.

Warhead Design

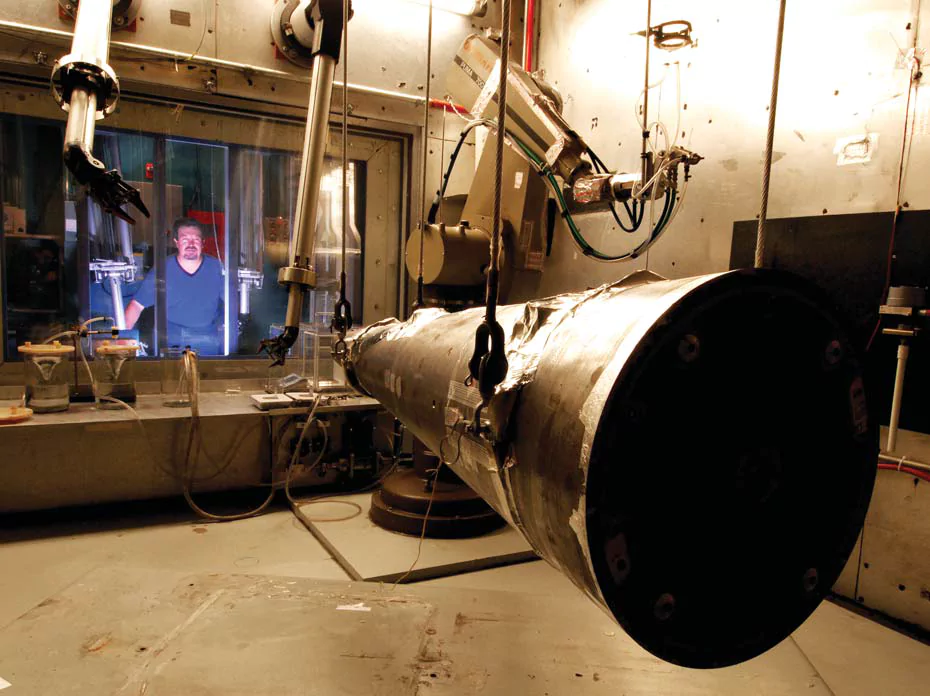

The British Trident warhead, known as the Holbrooke Mark 4, closely resembles the U.S. W76 warhead, making it integral to the W76 engineering, design, and evaluation schedule. Designed to fit the Mark 4 RV, a cone-shaped structure approximately five feet (152 cm) in length and 16 inches (41 cm) in diameter weighing about 212 pounds (96 kg), the British warhead was based on U.S. blueprints.

Preliminary design began in 1980 at AWE Aldermaston under Denis Dracott as Chief of Warhead Design, with the final configuration completed in 1987. Despite being developed and manufactured domestically, the UK relies on the U.S. for critical non-nuclear components, including the neutron generators and tritium gas used to manipulate yield, as well as the re-entry body, Arming Fusing and Firing system, and potentially the tritium gas transfer system.

The warhead yield is variable, offering yields of approximately one kiloton (achieved by removing the tritium boosting), ten kilotons (by ‘switching out’ the thermonuclear stage), and 100 kilotons (using the total fission plus fusion yield).

The UK warhead was tested three times at the US Nevada Test Site during its development.

Safety Features

Although detailed safety specifications remain classified, the UK Trident warhead incorporates advanced safety technologies. Current UK Trident warheads feature a one-point safe design, ensuring that accidental detonation at any single point will not trigger a significant nuclear reaction.

The Oxburgh Report described these safety technologies as “state-of-the-art for their time” and safer in some aspects than the earlier Chevaline system.

Potential features include Insensitive High Explosive (IHE), reducing accidental detonation risks, Fire Resistant Pits (FRP), protecting plutonium cores during fires, and Enhanced Nuclear Detonation Safety (ENDS), introduced in the U.S. in 1977 to prevent unintended detonations.

However, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) has not publicly confirmed the specific use of these technologies.

Production

Trident warhead production began in 1987 at Aldermaston’s existing A45 facility, initially supplementing limited capacity until new A90 facilities became operational.

The warheads for the first submarine, HMS Vanguard, were manufactured at the A45 facility, with fissile component production starting in January 1988 and the first batch completed in September 1992.

The A90 facility, originally due for completion in 1986, was plagued by delays and was only handed over to the Director of Operations at AWE in October 1991. The facility began delivering finished components by late 1992. Warheads for the remaining three Vanguard-class submarines were produced by the A90 warhead production complex.

Warhead production was planned over approximately a ten-year period, requiring two years to reach full production levels.

A large proportion of fissile materials was domestically sourced from British Nuclear Fuels Limited, although highly enriched uranium continued to be sourced from the U.S. Fissile material from retired Chevaline warheads was also reused.

Deployment

The Trident warhead entered operational service aboard HMS Vanguard, the first Vanguard-class submarine, in 1992. Each submarine carries up to 16 Trident II D5 missiles with a maximum of three warheads per missile, for a total of 48 warheads per submarine patrol.

Missiles and warheads are tested and maintained with U.S. oversight at the missile test areas off the U.S. Atlantic coast and at RNAD Coulport, respectively. U.S. personnel assist in missile handling, repairs, and fitting warheads before deployment on continuous-at-sea deterrent patrols.

Life extension

The UK Trident warheads are undergoing significant updates, aligned with the U.S. W76-1 life extension program.

The U.S. W76-1 refurbishment program extends the life of the original W76 by approximately 30 years, refurbishing critical elements including the nuclear explosive package, the arming, firing, and fuzing system, and the gas transfer system. A central component is the upgraded Arming, Fuzing, and Firing (AF&F) system, enhancing targeting flexibility and accuracy.

Sandia National Laboratories conducted the first UK W76-1 trial in March 2011 at their Weapons Evaluation and Test Laboratory (WETL).

The Mk4A Reentry System upgrade commenced as part of the UK Trident Weapon System Life Extension Program, with production and implementation expected between 2014 and 2018, as indicated by official documentation from the UK Ministry of Defence.

This upgrade aligns British SLBMs with the U.S. W76-1/Mk-4A version currently in production and operation.

Further Reading

Bibliography

- U.S.-UK Nuclear Cooperation After 50 Years. (2008). United Kingdom: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- Jinks, J., Hennessy, P. (2015). The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service Since 1945. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited.

- Arrieta, M. (2014). Project on Nuclear Issues: A Collection of Papers from the 2013 Conference Series. United States: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- Norris, R. S., Burrows, A. S., Cochran, T. B., Fieldhouse, R. W. (1994). Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume V: British, French, And Chinese Nuclear Weapons. United Kingdom: Avalon Publishing.

- The British Nuclear Weapons Programme, 1952-2002. (2004). United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- The future of the UK’s strategic nuclear deterrent: the manufacturing and skills base, fourth report of session 2006-07, report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence. (2006). United Kingdom: Stationery Office.

- Global security: UK-US relations, sixth report of session 2009-10, report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence. (2010). United Kingdom: Stationery Office.

- Larkin, B. (2018). Nuclear Designs: Great Britain, France and China in the Global Governance of Nuclear Arms. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Ritchie, N. (2012). A Nuclear Weapons-Free World? Britain, Trident and the Challenges Ahead. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Futter, A. (2016). The United Kingdom and the Future of Nuclear Weapons. United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Haynes, S. T. (2016). Chinese Nuclear Proliferation: How Global Politics Is Transforming China’s Weapons Buildup and Modernization. United States: Potomac Books.